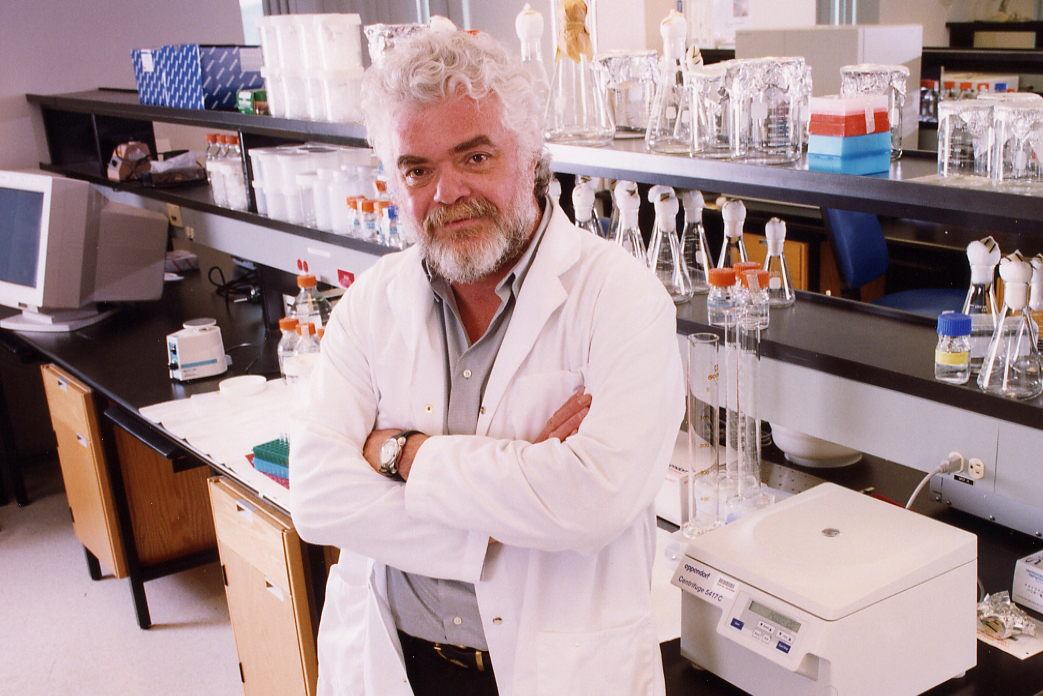

Dr. Frank Plummer, who passed away in 2020, was a trailblazing medical microbiologist in the area of sexually transmitted infections.

Marking 140 years of health research impact

The Max Rady College of Medicine at UM is marking a milestone. It’s been 140 years since it was founded in 1883 as the Manitoba Medical College, Western Canada’s first medical school.

On Nov. 18, UM alumni, partners, faculty members, students and friends of the college will celebrate the 140th anniversary at a gala at the RBC Convention Centre. The event will raise funds for MD and grad student bursaries.

While the medical college has educated generations of physicians and served the community, it has also been a thriving centre for the advancement of medical science.

“We’re known for punching above our weight in terms of our research achievements,” says Peter Nickerson [B.Sc.(Med.)/86, MD/86], vice-provost (health sciences) and dean of the Max Rady College of Medicine and the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences.

“Each year, the college brings in more than $100 million in external research funding. Our investigators, including master’s and PhD students, conduct multidisciplinary research that influences health policy, improves patient care and saves lives.”

From innovative disease research carried out in labs and at hospital bedsides, to studies that give a voice to under-represented patient groups, to findings gleaned from one of the world’s richest storehouses of health data – the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository – the Max Rady College of Medicine is constantly generating new knowledge.

“Our strengths include being exceptionally collaborative, forging effective external partnerships and reaping the benefits of intergenerational chains of research mentors and mentees,” says Nickerson, a kidney specialist who is himself a distinguished research scientist.

In addition to the acclaimed faculty members and alumni who are laureates of the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame – we’re spotlighting them in a list on Nov. 16 – here are 10 Max Rady College of Medicine research highlights that have made an indelible impact.

Dr. Lorrie Kirshenbaum

• In 1948, a cardiologist convinced nearly 4,000 air force veterans to enrol in a study of their cardiovascular health. The extraordinary project, based at UM and known as the Manitoba Follow-up Study, is one of the world’s longest-running health studies of a specific cohort. One of its findings in the 1990s was that shorter men are at greater risk of dying of heart disease than taller men. The study, now led by Robert Tate [M.Sc./75, PhD/00] and marking 75 years, is still tracking a handful of surviving participants. Meanwhile, UM scientists like Lorrie Kirshenbaum [B.Sc./86, M.Sc./88, PhD/92], Canada Research Chair in molecular cardiology, are engaged in leading-edge cardiovascular research. Kirshenbaum has earned international recognition for his work on cardiac cell death and its impact on the development of heart failure.

Dr. Edward (Ted) Lyons

• In the mid-1960s, UM radiologist Edward (Ted) Lyons [B.Sc./63, B.Sc.(Med.)/68, MD/68] became one of the earliest pioneers of ultrasound. His groundbreaking research helped to establish ultrasound as safe for fetuses and mothers, and his findings influenced hospitals across the globe to adopt the technology. Lyons led the first lab in Canada to perform general ultrasound. For years, he worked with manufacturers to evolve the technology from a machine the size of a refrigerator to a portable device no larger than a cellphone. He has called himself “a traveller on a stream of new imaging technology.”

Dr. Stephen Moses

• Frank Plummer [MD/76], who passed away in 2020, was a key member of a multigenerational chain of researchers who have worked for more than 40 years in partnership with the University of Nairobi, making high-impact discoveries in the area of sexually transmitted infections. In the late 1980s, Plummer led a UM team in discovering that some Kenyan women sex workers who had been exposed to HIV infection were naturally immune to it. This breakthrough provided vital new information for HIV vaccine and drug development. In 2007, UM’s Dr. Stephen Moses co-led a study showing that circumcision reduced the risk of HIV infection by 50 to 60 per cent in men who had heterosexual sex. This insight was named one of the biggest medical breakthroughs of the year by Time magazine.

Dr. Heather Dean

• In the late 1980s, when Type 2 diabetes was considered an adult-only disease, UM pediatric endocrinologist Dr. Heather Dean and her colleagues made the startling discovery that some First Nations children in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario had the disease. They published the first paper about these children in 1992. Dean went on to work closely with First Nations communities to better understand the disease. Today, UM researchers continue to study many aspects of youth-onset Type 2 diabetes, including following a cohort of offspring of First Nations individuals who were first diagnosed as children.

Dr. Ryan Zarychanski (Photo: Doctors Manitoba)

• In 2012, a breakthrough by UM and CancerCare Manitoba scientists made the cover of Blood, the world’s top medical journal on blood disorders. The study, led by Dr. Ryan Zarychanski [B.Sc./95, B.Sc.(Med.)/00], identified the genetic mutation responsible for the hereditary blood disorder xerocytosis. Groundwork for this discovery had been laid 40 years earlier by UM hematologist Lyonel Israels [MD/49, M.Sc./50], founding father of CancerCare Manitoba. Zarychanski now holds the Lyonel G. Israels Research Chair in Hematology. This year, he was named Physician of the Year by Doctors Manitoba for leading international clinical research to rapidly assess potential treatments for COVID-19.

Dr. Gary Kobinger

Dr. Jason Kindrachuk

• During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, UM’s Dr. Gary Kobinger was chief of special pathogens at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg. His team of UM and PHAC researchers co-developed an experimental antibody cocktail called ZMapp. In 2014, it was used in saving the life of an American doctor with Ebola – a dramatic event that made international headlines. Today, Dr. Jason Kindrachuk, Canada Research Chair in the molecular pathogenesis of emerging viruses, is keeping UM on the map as a virus centre through his work on viruses such as Ebola, mpox and coronaviruses.

Dr. Marcia Anderson

• UM is a national leader in partnering with Indigenous communities in health research. In 2019, for example, a landmark joint study by the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba and the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy in the Max Rady College of Medicine illuminated the worsening health gap between First Nation people and all other Manitobans. This year, UM’s Marcia Anderson [MD/02] took a leadership role in making Manitoba the first province to systematically ask hospital patients to voluntarily declare their race, ethnicity or Indigenous identity. The purpose of collecting this data is to address racial inequities in health care.

Dr. James Blanchard

• In 2022, health research and programming in India led by James Blanchard [B.Sc.(Med.)/86, MD/86], executive director of the UM Institute for Global Public Health, received a major injection of support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The funding of US$87 million will support reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health in the state of Uttar Pradesh. In total, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has invested US$280 million in international UM projects. The Institute for Global Public Health has been a world leader in forming partnerships to strengthen health systems and influence health policy, particularly in countries in Asia and Africa, says Blanchard, who holds a Canada Research Chair in epidemiology and global public health.

Dr. Ruth Ann Marrie

• An internationally renowned multiple sclerosis (MS) researcher at UM, neurologist Dr. Ruth Ann Marrie, directs the MS Clinic at Health Sciences Centre. This year, Marrie received a prestigious U.S. prize for her trailblazing body of work. She and her team were the first to explore the implications of comorbidities such as high blood pressure and heart disease in people with MS. She has also shown that the disease may have a “prodromal phase” that precedes the onset of specific MS symptoms. Her ongoing research is laying important groundwork for both prevention and improved treatment of MS.

Dr. Meghan Azad

• Meghan Azad [PhD/10] is a worldwide expert on the science of breast milk. She holds a Canada Research Chair in developmental origins of chronic disease at UM and is also a researcher with the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba. This year, she and her team landed a grant of US$2.5 million from a prestigious U.S. funder, the National Institutes of Health. The project will include in-depth lab analyses of milk samples from 1,600 mother-child pairs, looking at breast milk in a way that is unique in the world. The data will then go to machine-learning experts at Stanford University, who will use artificial intelligence to explore it. The study is expected to generate the world’s largest and most detailed dataset of mothers, infants and breast milk.