Louis Slotin (left) and fellow students, Harvey Cohen (centre) and Charles Alan Ayre (right) in chemistry lab at the University of Manitoba, ca. 1933-34. // Photo: University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections

Louis Slotin: The life and death of a UM alum at Los Alamos

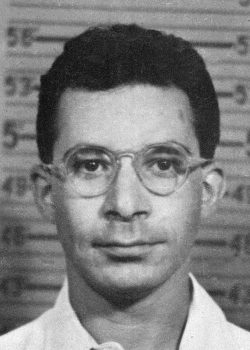

Louis Slotin during Manhattan Project, ca. 1944. Credit: Los Alamos National Laboratory, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Shortly after 3:20 p.m. on May 21, 1946, University of Manitoba alumnus and physicist Louis Slotin walked out of a laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico, home of the Manhattan Project. He didn’t seem much different than he had been moments earlier, but he knew that he was now a dead man walking.

With the war over, Slotin had been looking forward to returning to the University of Chicago in the fall, and was demonstrating a critical mass experiment to his replacement, Alvin Graves, and six others.

The demonstration was one that he had performed many times before. It involved a softball-sized plutonium core nestled in an upward-facing hemisphere of beryllium. As another hemisphere was slowly lowered over the core, neutrons were increasingly reflected back, edging the core towards criticality. The risky procedure was nicknamed, “tickling the dragon’s tail”.

Wanting finer control, Slotin removed the shims that acted as safeguards to keep the two hemispheres apart – if they closed completely, an extremely dangerous super-critical state would be initiated.

Tilting back the upper hemisphere with his left hand, he used a long screwdriver as a lever to slowly lower the open side of the hemisphere over the core, until only a narrow gap remained.

Suddenly, the screwdriver slipped and the hemisphere slammed shut over the core. The men in the room saw a bright blue flash of light and felt a wave of heat wash over them. Slotin immediately yanked away the hemisphere to stop the chain reaction, but the damage was done.

A re-enactment of Slotin’s criticality experiment. Credit: Richard G. Hewlett, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Being closest to the critical assembly, Slotin received a massive dose of radiation — several times the lethal amount. Because of his quick reaction, the other seven people received lower exposures and would survive.

Slotin knew exactly what lay ahead. His friend, Harry Daghlian, had died just nine months earlier performing a similar experiment, but using tungsten-carbide bricks. He was at Daghlian’s bedside every day as his friend died an agonizing death over the course of nearly a month.

Slotin’s parents arrived from Winnipeg four days after the accident. He was still in good spirits and was sitting up in bed. But by the fifth day, his condition rapidly deteriorated as his white blood cell count plummeted and his gastrointestinal system began to fail. On the eighth day, he was placed in an oxygen tent and fell into a coma. He died on May 30, nine days after the accident. He was 35 years old.

Louis was the eldest of Israel and Sonia Slotin’s three children. The family lived on Alfred Avenue in the North End until 1933, when they built a house on Scotia Street. Slotin attended Machray School and then St. John’s Technical High School. Excelling academically, he was only 16 when he enrolled at the University of Manitoba. Slotin graduated with a B.Sc. (Hons) in 1932, and received the University Gold Medal in physics and chemistry. He completed an M.Sc. degree a year later under the supervision of Alan Newton Campbell.

After receiving a doctorate at King’s College London, he became a research associate at the University of Chicago, where he helped to build its cyclotron. In 1942, he was recruited for the Manhattan Project and was transferred from Chicago to Los Alamos in 1944. There, he helped assemble the core of the first atomic bomb used in the Trinity test.

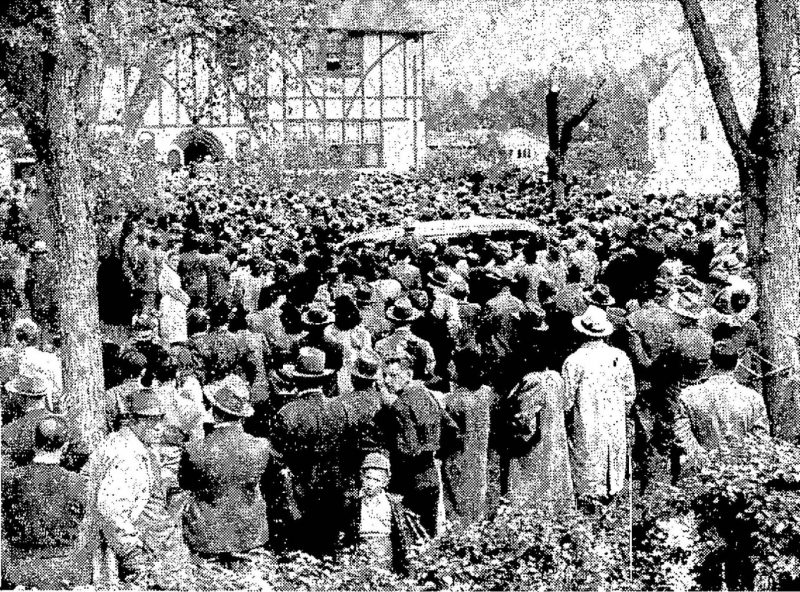

Crowd attending funeral service outside the Slotins’ home on Scotia Street, Photo: Winnipeg Free Press / published June 3, 1946 / reprinted with permission

Thousands turned out for Louis Slotin’s funeral on Sunday June 2, 1946, filling the street in front of the family’s home where the service was held. Among those in attendance was future UM chancellor Henry Duckworth, who would later call Slotin “one of the genuine heroes of the Atomic Age”. Because of his service to the United States government, Slotin’s casket was draped in the American flag. He was laid to rest at the Shaarey Zedek Cemetery.

Today, a short walk from the family’s old home, lies a small park at the foot of Luxton Avenue that is named in his honour. A plaque there details Slotin’s life and untimely death.

Wayne Chan, is a research computer analyst for the Centre for Earth Observation Science, but he is also an avid researcher who loves history. Please check out this feature on Chan in UM Magazine.