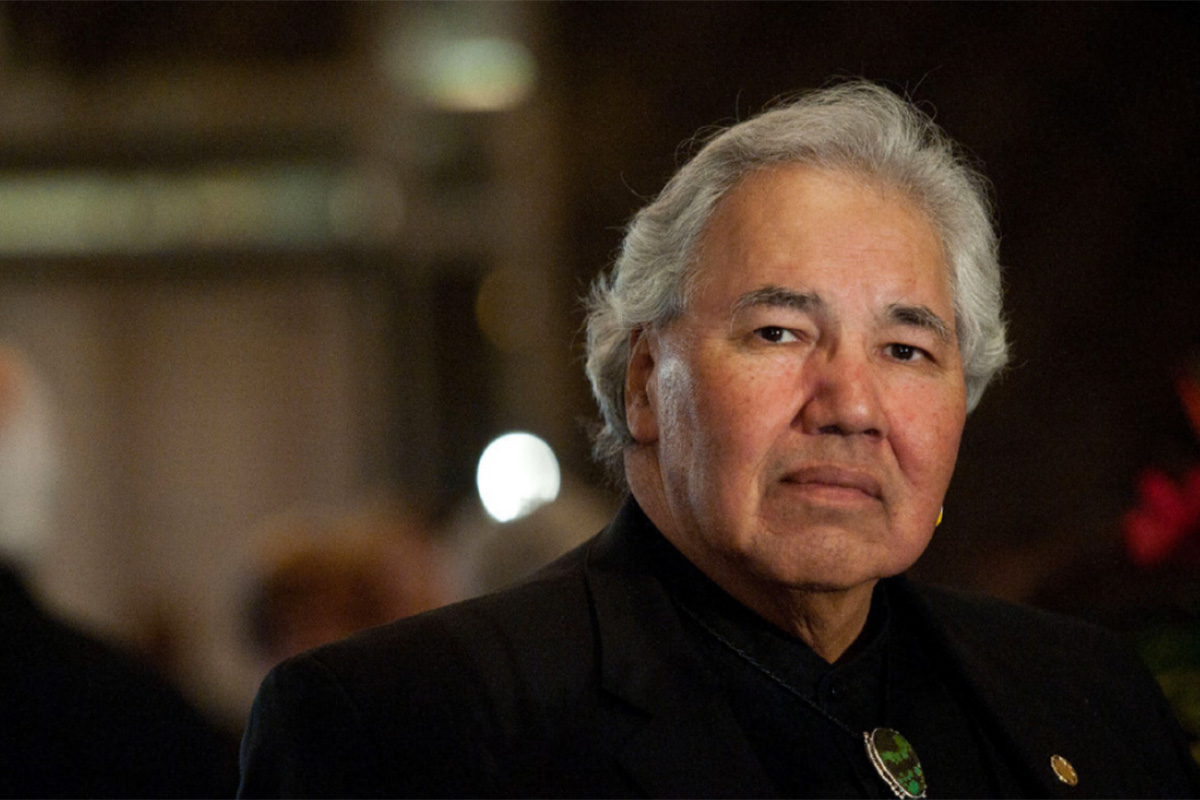

The University of Manitoba mourns Justice Murray Sinclair

Canada’s truthteller has died at age 73

Mazina Giizhik (the One Who Speaks of Pictures in the Sky), the Honourable Justice we commonly know as Murray Sinclair, the man who listened to thousands of Survivors of residential schools as Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), died on November 4 at the age of 73.

“In his every role, the Honourable Murray Sinclair was a moral compass, guiding us all towards the path to Reconciliation, and on behalf of the University of Manitoba, I extend our condolences to his family,” says President Michael Benarroch. “The University of Manitoba is committed to honouring his legacy by furthering Reconciliation efforts within our community and beyond. We are deeply honoured to be host to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, which came about through Sinclair’s leadership and advocacy. And though his vision and voice will be profoundly missed, they will continue to inspire us toward a more just and inclusive future.”

In 2002, when Sinclair received an Honorary Degree from St. John’s College at the University of Manitoba, his son Niigaanwewidam Sinclair—now a Professor in the Department of Indigenous Studies—questioned his decision to accept an honorary degree from a religious institution involved in residential schools. As Niigaan later recounted, his father didn’t respond directly but instead took the stage before church leaders and called for the creation of what would become the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. When he stepped off the stage, he told Niigaan, “That’s why I do it.”

“He made an argument for an investigation into the issue of residential schools, and that this country needs to commit to survivors and listen to them and believe them,” Niigaan remembered in a conversation with president Benarroch.

Six years later, in 2008, the TRC was charged with documenting the experiences of Survivors, their families, and communities affected by Canada’s residential school system, uncovering the truths about this dark chapter in Canadian history, and setting the foundation for Reconciliation efforts.

As commissioner, Sinclair [LLB/79, LLD/02] led the TRC’s efforts to collect over 6,500 testimonies from residential school survivors, many of whom bravely shared their experiences for the first time. This work resulted in the publication of the TRC’s findings, including the landmark 94 Calls to Action, which have become guiding principles in Canada’s ongoing journey toward Reconciliation. Recognizing the importance of preserving these stories for future generations and ensuring accountability, Sinclair advocated for the establishment of a permanent home for the TRC’s records, testimonies, and research findings.

This advocacy laid the groundwork for the founding of the NCTR, which officially opened at the University of Manitoba in 2015. As a steward of the TRC’s archives, the NCTR serves as a vital resource for education, research, and commemoration, helping Canadians confront the legacy of residential schools and work toward meaningful Reconciliation.

“This loss is so profound. I personally got to work with the Honourable Murray Sinclair years ago and his contributions to Indigenous rights, education, and justice have forever transformed Turtle Island, and he did it all with kindness, humility and wisdom,” says Angie Bruce, Vice-President (Indigenous). “He is truly an inspiring figure whose legacy of leadership and truth telling will live on. The UM community is so grateful to have shared time with him, and to have had a role in his story. We extend our deepest sympathies to his family and all those who had the privilege of learning from and working alongside him.”

Yet Sinclair’s career of listening and telling the truth about broken systems—and who they fail—almost didn’t happen because the man tasked with being witness to the testimonies from the thousands of Indigenous people harmed in residential schools, mostly by Catholic priests, almost became a priest himself.

His grandma, as a young woman, was intent on becoming a nun but when she decided to leave the convent, she could only do so in exchange for a pledge to foster this commitment in a child. Sinclair grew up understanding he would fulfill that promise and she didn’t let him date until his 20s, in preparation. When he finally pushed back, she conceded, but had him vow he would do something good with his life.

With $1,000 his grandma—his beloved kookum—saved, he pursued a law degree at the University of Manitoba, but he wasn’t always convinced he wanted to be part of a system that felt so discriminatory.

As an Anishinaabe lawyer who sometimes got mistaken for the accused, Sinclair pushed through and would become Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge. He led the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry into the role racism played in the investigations of murdered Cree teenager Helen Betty Osborne and the police shooting of Indigenous leader J.J. Harper.

He grew up with a sister and two brothers on the St. Peter’s Reserve near Selkirk, Man.

Their grandmother and their aunts raised them following the death of their mother, Florence, from a stroke not long after his youngest brother was born. It wasn’t until Sinclair’s involvement with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that he learned his father was among those sexually abused in residential school. He heard from his uncle how his dad, at age 10, was able to alert his grandma since she lived nearby. She managed to take back her kids and move away.

It was one of thousands of horrible stories. Sinclair later said he did not anticipate how difficult a burden it would be to assume the role of truth finder and teller.

“Whenever they cried, we cried with them,” Sinclair told UM Today the Magazine. “We didn’t really appreciate just how heavy it was going to be. Winnipeg was our first major set of hearings and after that session was over and we were debriefing I can remember one of the commissioners saying, ‘My God, are they all going to be like this?’ And they all were.”

But Sinclair never let negativity take over. “I don’t sit around weeping, feeling sad and feeling angry,” he said. “You can easily go back and look at all the bad memories and sad memories and let that dominate your sense of self, but I don’t do that. I acknowledge them. I speak of them and I learned early on, utilizing traditional approaches, how to memorialize them so that I didn’t have to live with them constantly.”

He would start each day with a prayer, singing as he played a drum. His huskies—one of them named Stevie (he’s a Fleetwood Mac fan)—would join in by howling. Today, the silence pains this country.

Mazina Giizhik, as the story goes, searches for answers to help his people and looks up for messages from Creator. And though we are now without him, we will be forever guided by the truth he uncovered and the lessons he left behind.