George Rubenfeld (centre) with his family in France, 1950. // Photo courtesy Belle Jarniewski, Voices of Winnipeg Holocaust Survivors.

Life after the Holocaust: Alumni who survived

January 27 marks the anniversary of the 1945 liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp during the Second World War – a day set aside by the United Nations to commemorate the Holocaust.

At war’s end, six million Jewish people were dead along with millions of other victims of Nazism. Among the survivors were children – many war orphans – who became graduates of the U of M.

This week, we reflect on the stories and accomplishments of these alumni in the face of tremendous adversity and tragedy.

GEORGE RUBENFELD [BPed/60]

Born in Belfort, France, Rubenfeld was 17 when Germany invaded the country in 1940. Although the roads were bombed as civilians fled the northern cities, Rubenfeld was able to escape south with his family. They relied on the kindness and bravery of many strangers who hid, housed and fed them as France surrendered and anti-Jewish legislation was enforced.

His family was forced to register as Jewish and assigned a residence to live so they could be tracked and – when the time came – round up easily for deportation. That time did come, but the Rubenfelds were warned by a friend and were able to escape.

While his sisters and parents fled to separate farms to hide, Rubenfeld joined the underground Resistance. Based out of a cabin in the woods, he helped plan and sabotage German military operations. More skilled with a violin than guns, Rubenfeld once participated in a benefit concert to help French prisoners of war. Like the Von Trapp family from The Sound of Music, he and his sisters performed in front of 25 Nazi officers, and were then immediately whisked away to safety.

The entire family survived the war, immigrating to Canada in 1953. Rubenfeld obtained his bachelor’s degree at the U of M and later served as an assistant professor in the Faculty of Education for 17 years. He died on Jan. 23, 1991, aged 67.

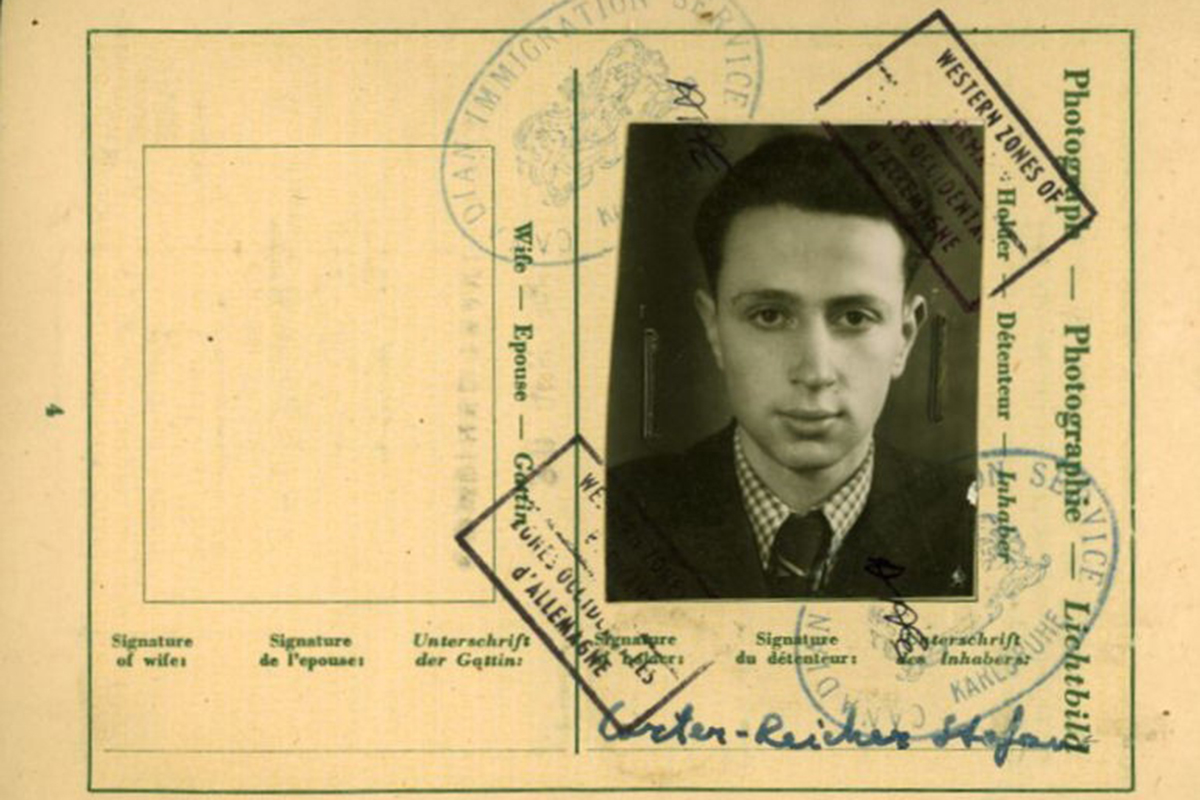

Stefan Carter's immigration visa, circa 1948. // Photo courtesy Belle Jarniewski, Voices of Winnipeg Holocaust Survivors

STEFAN CARTER [MD/54, MSc/56]

Carter was imprisoned in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, aged 12. After his mother was sent to the Treblinka death camp, two cousins smuggled him out; his father is suspected to have died in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

For two years, Carter hid in several Polish Christian homes. He was once betrayed by a neighbour to police, but escaped arrest when the officers asked him to drop his pants and saw that he was uncircumcised – an anomaly for Jewish boys. He proceeded to further hide his identity by undergoing surgery at a local clinic to alter his nose. By obtaining false Aryan papers and learning Catholic prayers Carter was able to live freely in Warsaw and its countryside until war’s end.

At 20, Carter immigrated to Canada where he became a renowned vascular specialist and participated in Manitoba’s first open-heart surgery in 1959. He was a professor in the Max Rady Faculty of Medicine for over 40 years.

Now in his 90s, Carter regularly speaks about his experience at high schools, universities and the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. He is the author of From Warsaw to Winnipeg.

Arnold Frieman at the grand opening of Advance Electronics in Winnipeg, 1967. // Photo from Advance Electronics

ARNOLD FRIEMAN [BA/60, LLD/18]

Frieman was a teenager studying in Budapest when Germany occupied Hungary in 1944. He rushed home to find his parents, grandfather, and five siblings had been sent to Auschwitz. Only two sisters, Elizabeth and Edith, survived.

He spent months on the run, then in a forced-labour camp before making a miraculous escape. After the war, Frieman received medical treatment in Norway and studied electronics – skills he put to immediate use with the Israeli Air Force.

In 1951, he immigrated to Winnipeg and pursued a university education thanks to a $1,000 gift from a friend, supplemented with money he earned fixing and reselling car radios. This talent eventually inspired Advance Electronics. Initially a two-person operation, it burgeoned into the largest independently owned electronics store in Western Canada.

Frieman was a prolific philanthropist; his generosity made possible the premiere of I Believe, a Holocaust oratorio that encourages awareness, understanding and peace. He received the Order of Manitoba in 2006 and was conferred an honorary degree from the U of M in 2018. Frieman died on Apr. 5, 2019, aged 90.

Susan Garfield (centre) with her parents before the war. // Photo courtesy Belle Jarniewski, Voices of Winnipeg Holocaust Survivors

SUSAN GARFIELD [BRS/86]

Garfield (née Loffler) was eleven years old when Hungary was taken by German forces. Her father was sent to a slave labour camp and disappeared on the Russian front while her mother was taken away by Hungarian fascist collaborators.

With the help of an aunt, Garfield was able to obtain Red Cross papers and flee the Ghetto before Jews were imprisoned there. She was shuffled from town to town, hiding with aunts and uncles, narrowly avoiding capture many times.

Garfield immigrated to Canada through the Canadian Jewish Congress’ War Orphans Project. She had hoped to complete high school and attend university, but her foster parents thought secretarial school a more suitable option. In 1954, she married Harry Garfield [BA/49, MD/55]. After raising a family together, she was able to earn her much desired degree at the U of M at age 53. She is the author of Too Many Goodbyes: The Diaries of Susan Garfield.

John Hirsch at the opening of Three Men on a Horse at Toronto's Royal Alexandra Theatre in 1987. // Reg Innell, Toronto Star Archives

JOHN HIRSCH [BA/52]

When Hirsch left his hometown of Siófok, at 14, to study in Budapest, it was the last time he ever saw his family. Germany invaded Hungary in 1944 and his parents and brother were deported to concentration camps. A maid hid Hirsch, then took him to the Budapest Ghetto.

After the war, Hirsch lived in a UN refugee camp where he and a friend staged a production of The Snow Queen for the children there. This theatrical talent was encouraged by his adoptive family when he arrived in Winnipeg at age 17.

Only a few years after learning English, Hirsch earned his degree in English literature from U of M and formed a children’s theatre company. In 1957, with Tom Hendry, he developed Canada’s first regional theatre: the Manitoba Theatre Centre.

He would go on to serve as head of CBC television drama and artistic director of Stratford Festival. He received an honorary doctorate from the U of M in 1966 and was named to the Order of Canada. In the U.S., he won an Obie Award, among others, for his theatre productions. Hirsch died on August 1, 1989, aged 59.

Walter Saltzberg, centre on stretcher, at a Russian military hospital post-leg surgery. // Photo courtesy Belle Jarniewski, Voices of Winnipeg Holocaust Survivors

WALTER SALTZBERG [BSc(CE)/57]

Saltzberg was eight when he escaped from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, never to see his family again. The building he hid in was bombed; Saltzberg was the lone survivor. Buried up to his neck, his leg broken, he was rescued by a friend who carried him into a 40-square-foot hiding space behind a public toilet.

They lived there with three other Jewish men until the end of the war, surviving on snow, rain and rotten onions. His broken leg went untreated for nine months. At war’s end, he received surgery in a Russian military hospital, then reconstruction in Sweden, but was left permanently disabled.

Saltzberg arrived in Canada at age 16 with a grade two education, a book titled 300 English Words, and no money. Ten years later, he graduated from the U of M and eventually became Director of Bridges and Structures for the Province of Manitoba. He was president of the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists and also served as engineer-in-residence at U of M. He often spoke publicly about his war experience to instill tolerance and was awarded a Sovereign’s Medal for Volunteers. Saltzberg died March 8, 2018, aged 88.

Do you have a story about an alumnus who survived the Holocaust? Let us know in the story comments below.

My mother, Caroline Dukes R.C.A (o.b.m 2003), an alumni graduate of the faculty of art at UofM and Holocaust survivor.

Brave, very brave people, all of them!

And these people were considered to be inferior to their captors. We need to keep this history open and available to others to ensure that this insanity will never reoccur.

With the passage of time, the ranks of living Holocaust survivors are thinned. Please let all humanity join today to remember this abominable tragedy. It is only in the act of remembering that we will be successful in seeing that such an atrocity does not repeat itself.

My father, Jonathan Geller. You can read more here:

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/article-holocaust-survivor-jonathan-geller-became-a-hipster-ahead-of-his-time/