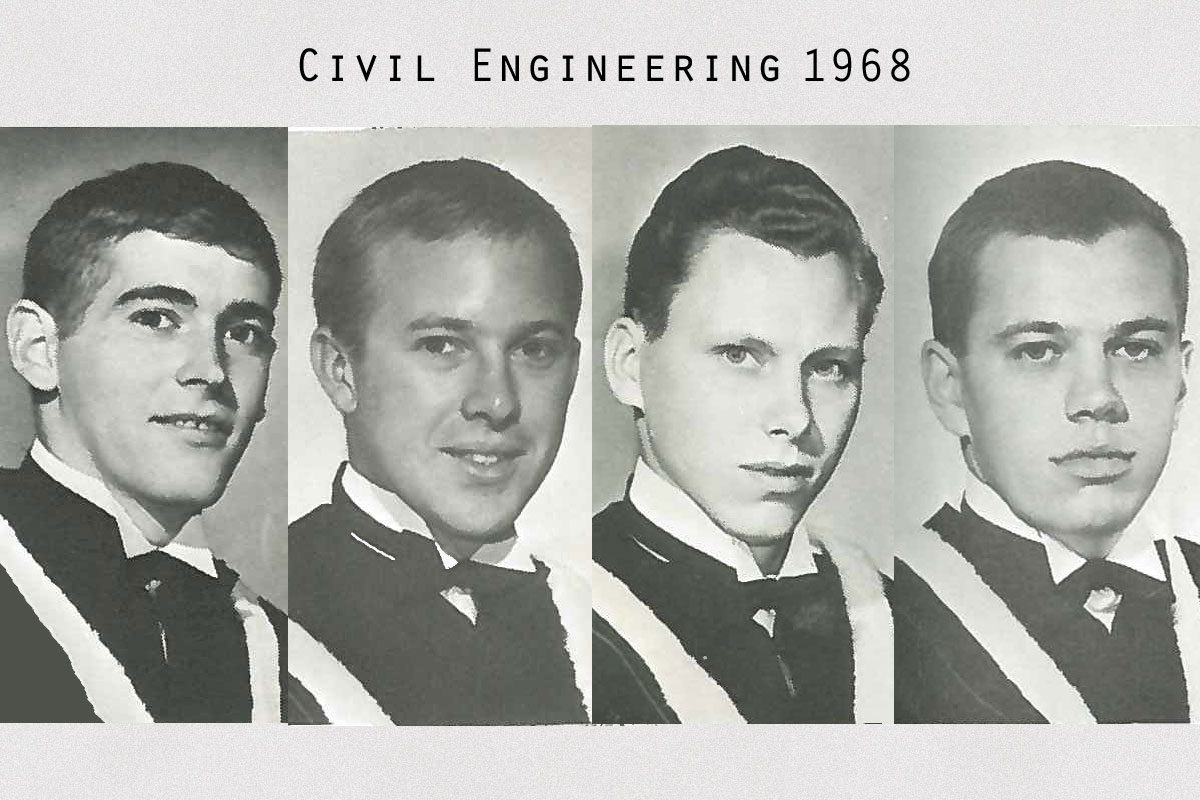

(L-R) Bruce Piercy, Douglas Holmes, Rick McKay and Edward Klemm.

Homecoming Throwback: Civil Engineering 1968

The 1960s were an influential time to be young. Hippies and counterculture were in vogue; rock and roll had invaded the airwaves; and the ongoing Vietnam War sparked protests in schools across North America.

In Canada, four young men – Bruce Piercy, Douglas Holmes, Edward Klemm and Rick McKay – were about to graduate from the University of Manitoba to pursue careers in civil engineering.

Last Friday, the four reconnected with others from their class at Homecoming to celebrate their 50th graduation anniversary. UM Today joined them to reminisce about student pressure and social life in the 1960s.

UM TODAY: WHY DID EACH OF YOU GO INTO ENGINEERING?

MCKAY: I was always good in math, so I went in for the mathematical end of it. I had a pretty good idea of what I was getting into.

KLEMM: I had a cousin that graduated civil engineering three years previous to me finishing high school. Then, during the summer, I got a phone call from a good friend of mine and he said “what are you doing this fall? Going to university?” And I said “Yeah, I guess so.” He says “well, I’m going into civil engineering.” And I said “OK! Sounds good.” I went through school, grade one all the way through, with no problem whatsoever. I wasn’t that concerned about anything.

PIERCY: When I applied to go to university, I applied for architecture. They wouldn’t let me in because my English marks were too low, but they said “we’ll let you in to engineering”. That’s how I ended up in engineering. Thank goodness.

HOLMES: I didn’t know what to take after high school and I thought, “oh an engineer, that sounds good”. I won’t have to work in an office; I’ll work outside. So I wasn’t in it because it was the thing I loved or aspired too. That’s probably why I found it difficult. I went through high school and it wasn’t too tough, but engineering – I had to study a lot. You had to work hard.

IT’S STILL A VERY INTENSE PROGRAM TODAY. IT’S ALSO QUITE A COMPETITIVE ONE TO GET IN TO. WAS THAT ALSO THE CASE FOR YOU?

HOLMES: It wasn’t as difficult as it is now. You had to have a certain average. I know of a young guy who graduated from St. Paul’s High School last year. I think he was the valedictorian, he won all kinds of awards, had a high grade point average, applied to engineering and didn’t get in. It gives you an idea – it’s really difficult.

MCKAY: Once you were in you’re in. But oh, you had to put time in, for sure.

KLEMM: I missed the lecture on ‘you have to do your assignments’. Because in high school, like Doug, I just breezed through. I didn’t even study for exams, I just passed. Then I get to university, and I thought it’s the same thing. I didn’t do the assignments and they’re worth 50 per cent of your mark or something. I didn’t hand in my first assignment in electrical to professor Halil.

MCKAY: Oh, he would have crucified you.

KLEMM: He says, ‘Ed, what the hell’s the matter with you?’ And I said “I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t come up with the right answer.” And he said “I don’t care. I want to see how you think. Just show me how you think and you’ll get a good mark for it. “You guys don’t remember this, but I became his favourite.

MCKAY: If you say so, Ed.

KLEMM: After one mid-term, we’re all sitting discussing the exam that we had written and he said “Ed stand up.” There was a question on the paper that you could answer two ways. You could answer with a three page answer or with a three line equation. I still remember to this day when I saw the question I thought “that’s worth 20 marks? Three lines?” I got an 86, the highest mark in the room. But he made me stand up and I was so damned embarrassed. We’d drink every Friday night at Champs and he’d always be there.

MCKAY: He hung with the students, yeah.

KLEMM: He’d challenge one of us to an arm wrestle. He had a barrel chest on him and arms like anything.

PIERCY: Oh yeah he was a tough guy.

AND YOU HAD TO DO ALL OF THIS WITHOUT MUCH TECHNOLOGY, RIGHT?

HOLMES: We had computers.

KLEMM: Well, just. The handheld calculator was just coming out. Remember that? It cost about $890 bucks. And you couldn’t bring it into the lab.

MCKAY: No, they wouldn’t allow it. We were hands on, it was that type of an education. We had slide rules to do our calculations. We would look upon the computer as a tool and even with those you had to program them with punch cards.

PIERCY: And if you screwed up the cards, it wouldn’t work. It was ridiculous, I got turned off it right away.

HOLMES: I was in the same boat. I hadn’t a clue about those computers. I don’t know how I got through that course, frankly.

MCKAY: When I was taking my masters, one of the courses I had to take was structural vibration. We were given a computer program and the solution was an iteration process. But it didn’t converge. Well, I walked into the lab one day and there were stacks of cards and paper wrappers everywhere. Because nobody had told the computer to grab the next number and put it in so it just kept going. They had to shut the system down to stop it because it would have been calculating still. That’s what I remember – if you made one typing error on those cards, that was it.

WHAT ABOUT TAKING NOTES? WAS IT DONE BY HAND OR DID YOU HAVE PHOTOCOPIERS?

MCKAY: They had the Gestetners [duplicating machine].

KLEMM: Yeah, but we weren’t allowed to use them.

PIERCY: We had what were called c-jobs.

WHAT ARE THOSE?

MCKAY: C-job is the guy that’s now in second year. Because you keep your labs, he gives you his labs so now you have a copy job. A c-job.

Present-day members of civil engineering ’68: (L-R) Doug Holmes, Bruce Piercy, Rick McKay, Ed Klemm.

IT SOUNDS LIKE YOU WERE A CLOSE-KNIT GROUP. WHAT DID YOU LIKE ABOUT YOUR CLASS?

KLEMM: I think it was just the guys. It was so much fun. It was the same guys in every class.

HOLMES: I don’t know how big the faculty is now but our class was big for its size at the day.

PIERCY: It was, yeah, we had 49.

HOLMES: But it felt more like being on a football team. A football team’s a larger team so you didn’t really know everybody in the class closely but you had groups. You stuck together.

PIERCY: More or less so. You knew something about everybody. I was surprised to read about how many guys were married which I didn’t know about!

HOLMES: And if they weren’t married they were getting married the year we graduated which must be pretty rare nowadays, I imagine.

KLEMM: We were the last class to not have women in it?

MCKAY: Probably. There were definitely women in the faculty behind us. But there were no women in any of the disciplines in our year.

JUDGING BY THE YEARBOOKS, IT SEEMS LIKE YOU WERE A PRETTY WILD BUNCH.

MCKAY: It gets instilled in you right from the start. I can remember first year, first day, when the Engineering band came through the graphics lab. They just grabbed you and you grabbed an instrument and marched. We went out, over to home economics, and they’re doing classes! We went into the rooms and walked around singing. That was day one. So that atmosphere gets ingrained in you right away. You have to understand, it was a different place.

HOLMES: The drinking age was different, too. It was 21.

BUT THAT DIDN’T STOP YOU GUYS.

PIERCY: No, we used to go to St. Charles, straight at the end of Notre Dame.

STORIES?

HOLMES: It was a pretty rough place, and it was old, really old. We found that if you went there in the afternoon and then wanted to come back at 6:30 you’d never get in.

So we all chipped in one night and tipped the manager $5 each. About eight of us come back at 6:00 and he takes us behind the registration desk where there’s a trap door. We go down into this basement that you can’t even stand up in, scurry around, find another trapdoor, and come up in the pub! We got first row seats.

KLEMM: Back in those days, you couldn’t go from one table to another with a beer in your hand. And when you went to the liquor store you had to sign your name and address.

MCKAY: You filled out the green form and you took it up to the counter and someone went and got you the bottle and brought it back to the counter. There was none of this open display stuff. That was the way it worked.

KLEMM: That’s why there were so many bootleggers in those days.

MCKAY: We might have partied a lot, but as a group, we were serious. This was your education. You were going to come out as a PEng. We were serious about it.