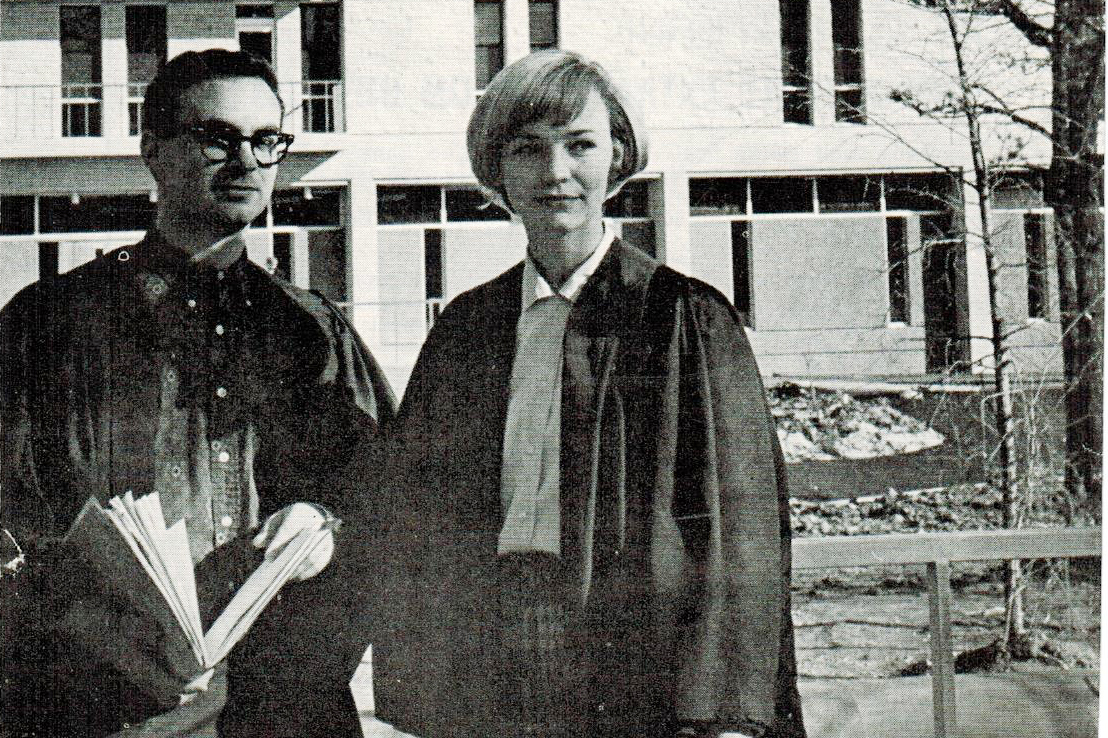

Ken Rubin (left) and fellow student outside University College. Photo: Ken Rubin

Alumni retrospective: Looking Back at University College

A failed and brief throw at being Oxford on the Prairies

In an over three-million dollar controversial new college building called University College, about 650 students—220 who resided there—came together back in September 1964.

To some at the University of Manitoba, it was a bold new experimental small arts and culture college attempting to depart from the general university’s factory-produced degree mill. But for others, the new University College was a bit of a throwback, a place for aspiring snobs, too ill-defined and without the history of other small religious-based colleges found on the University of Manitoba campus.

It was the place where in October 1964, I ran a campaign to head the student society asking for a mandate for a changed student educational atmosphere. I won by 33 votes, with a 65 per cent turnout, to become University College’s first student president, with a grand title of Secretary General.

We had many active students and committees and engaged in student lounge debates, our own newspaper writings and more. Sometimes, our student executive agendas that year contained burning issues like how to break up passionate daytime necking in the student lounge or whether the College should (and did) get a cigarette machine. Our executive and students were active; we even engaged in accountability sessions.

Many of the students I’m sure turned out quite well and indeed, my fellow student executives included those ending up becoming a Trinidadian political leader, a Manitoba cabinet minister, a history professor and who knows what else.

As experimental educational pioneers, we all had to wear purple robes and were expected to be somewhat different on campus. And the place did attract its fair share of non-conformists, even if most were far from being prairie populists.

We managed in year one to survive the campus’s ribbings and even had a few decent intra-mural sports teams and heck, we threw a few good parties. And there was always someone near the student lounge getting up to give the rest of us passing by a good rant.

The provost and leading advocate, Canadian historian W. L. Morton, wanted dearly to create an oasis of learning, dignity and exchange, a smaller place with a limited student enrollment. Some said this was his version of a kind of Oxford on the Prairies or as others said, an Oxford on the Red (hey, the building is after all near the Red River).

Morton was determined to see his college dream gather momentum, even at one point kindly chewing me out when I entered his office forgetting to wear my purple robe. He used to bemoan students not wanting to attend his feasts in the Great Hall dining room where his prominent invited guests gave speeches from the sanctity of the high table .

True, though, some of Provost Morton’s College guests were fun, educational and boisterous like author and wildlife advocate Farley Mowat in his kilt ready to spark things up.

Mind you, W.L. did not appreciate me all the time in helping out with his eminent high table guests. Once, for instance, after a high table feast for the executives of Eaton’s and the Hudson Bay Company, he asked me to show them a typical residential student room, I found the first open door, and the illustrious guests entered a room piled high with beer bottles and plastered with Playboy pictures. Heard about that alright.

Some students even went as far to satirize the College’s daily feasting pretensions, climbing up the rafters of the main dining room’s Great Hall, and setting up their own High-High Table.

But W. L. did, however, in the end back in 1965 as my term as student president drew to an end, praise me for my leadership in year one of a new era and wrote to me, quote, “for all the many services you have rendered the College.” Even got a going away present of, you guessed it- a plaque with a miniature Red River cart mounted on it.

His dream not quite happening, W. L. Morton left in 1966 to try out being a Provost at another small college, part of Trent University, again near a river (the Tweed River) in Peterborough, Ontario, where shortly thereafter I visited him.

University College lingered on for the next few decades, Its gowns became optional, and its high principles, its robust widespread student involvement in College life and special discussions faded. But for some, it provided a valuable experience that remains with us decades later.

It’s sad to know that University College is now no more than just another building at the University of Manitoba, a part of Arts and Sciences, without its own separate faculty or a thriving student body.

But for a brief moment in time, we brought academic high hopes, purple robes and a sense of community to the plains of the Red River in suburban Winnipeg’s higher education institution.

It is said that, without debating this thesis or putting faith in any one further mere building, that every fifty years or so something will rise up along the banks of the Red River besides flood waters and a human rights museum.

In 1965-66, Ken Rubin followed up his University College student presidency becoming the special assistant to the University of Manitoba Student Council President. In 1967-68, Rubin came back to campus for a year to be on the political science faculty as a seminar leader and researcher studying Canadian company towns, that included doing field research examining the power structures in Pinawa, Thompson, Churchill, Gillam and The Pas and other resource communities.

Ken Rubin went on to become a well-known Ottawa-based investigative researcher whose work on the national stage is featured on his website, kenrubin.ca. He sends belated greetings to all of his fellow students.

A wonderful experiment! Proud to have been a part of it and a graduate of University College. I did go on to teach in Oxford, albeit in the Oxford and County School District while Wilson studied in St. John’s College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. It’s been a wonderful life. Thanks UC Art’s and U of M.