The first graduating faculty of the new Teaching Learning Certificate program at the celebration luncheon on Sept. 23.

Teaching Learning Certificate alters a common trajectory for new faculty

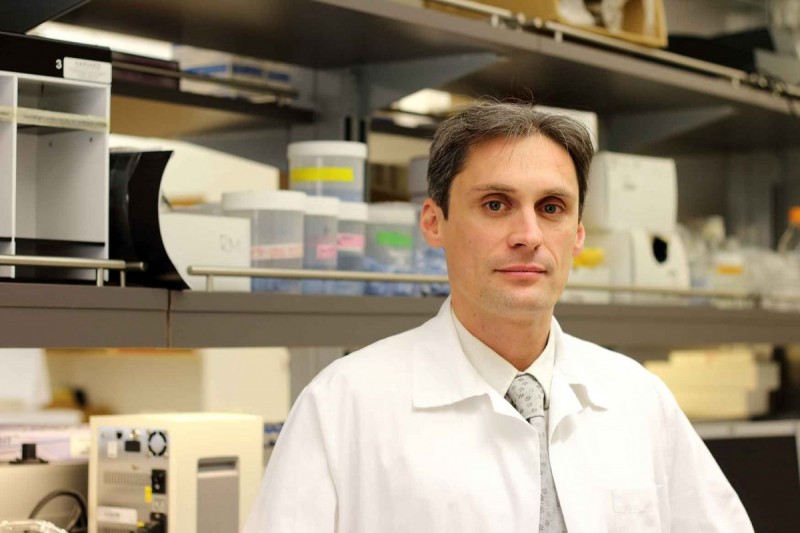

As Jean-Eric Ghia pursued an academic and research career, he was enthusiastic about jumping into teaching. He had been surrounded by educators his entire life — his father and mother, aunt, godfather and wife all teach. Being immersed in the educational environment, he was confident the teaching would come easy.

Jean-Eric Ghia says that his teaching has improved “exponentially” through enrolment in the Teaching Learning Certificate program.

Those positive feelings were quickly hampered by reality. His first attempts at teaching were “a disaster,” says Ghia, who’s now an associate professor in immunology and director of the Gastrointestinal Basic Biology Research at the IBD Clinical and Research Centre in the Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences.

Since enrolling in the inaugural Teaching Learning Certificate program in 2014 through The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning (The Centre), he says his teaching has “exponentially improved.” On September 23, 2016, the Centre celebrated the completion of the certificate program by its first group of faculty members; the program is designed to support and develop the teaching skills of new faculty.

Improving on bumpy first attempts

The trajectory — from believing teaching will be easy to the reality check of bumpy first attempts — is not an uncommon experience for faculty and instructors.

After taking the Teaching Learning Certificate, assistant professor Cathy Rocke was asked to become a mentor for the program.

When Cathy Rocke, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Social Work, got a last-minute request to teach an academic course — her first — on the topic of family violence in 1999, she leapt at the chance. She had experience in the social work field but none in teaching.

“How hard could it be?” she thought, given that she knew the content area. She expected to pick up a textbook and “wing it” with interesting discussions from her own lived experience.

It was a classic case of not knowing what she didn’t know, she says now. “Needless to say, the course was a disaster. I basically read the textbook as the class went along, prepared a few notes and questions and hoped for the best! I did not prepare a lesson plan, identify course objectives or use any student engagement techniques, and [I] expected written assignments without any plan to align [with] the curriculum.”

Her student evaluations were a concern to her. Rocke “dusted off her ego” and decided she needed to learn how to teach, enrolling in a one-week training course. It helped. Teaching as a sessional, however, she was largely unaware of teaching resources at the university and felt that she was “muddl[ing] along, learning from past mistakes to slowly improve my teaching ability,” she notes. Upon joining the faculty in 2010, she says she relied on lecturing and Power Point notes in her teaching due to her anxiety. Student evaluations still reflected a lack of student engagement.

All of it led her to seek more training. In 2014, she became part of the first cohort of the Teaching Learning Certificate program through The Centre. She says that it has improved her skills and helped her to devise a professional development plan — so much so that she’s been asked to be a mentor in the program, work she has already begun.

Rocke used her early difficult teaching experiences to motivate her to find ways to improve. And she adds, “I am a firm believer in lifelong learning and will continue to seek out ways to improve my teaching skills through ongoing professional development.”

In-class observation, mentoring at heart of competency-based program

The Teaching Learning Certificate is a two-year program that helps faculty members and instructors develop knowledge, skills and reflective practice. What makes it completely unique, says Colleen Webb, educational developer and co-designer of the program at the Centre, are two things: the mentoring-and-observation component and the fact that it’s a competency-based program.

Vice-Provost (Academic Affairs) Diane Hiebert-Murphy spoke at the Teaching and Learning Certificate Graduate Luncheon on Sept. 23.

Webb explains, “We wanted something that was measurable and where people could get recognition for their efforts. So we designed a program that recognizes the teaching knowledge people already possess, builds on that knowledge — and when they come out at the end, there would be some measureables. That was very important for us.”

To hit that objective, the program was designed so that participants would come out of the course with a completed teaching dossier for promotion and tenure purposes.

Besides helpful workshops on various teaching topics, the program offers observation and feedback on classroom teaching, as far as possible by mentors with similar backgrounds who are paired with the participants. As Webb says, “You can’t just conduct workshops and give faculty and instructors teaching tips. It has to be supported in the classroom.”

It was a learning experience for everyone, but the first cohort round went very well, she adds.

“The mentoring piece is key to the program. Mentors not only observe you in the classroom — they are also there throughout the two years to support you. And whether [participants] have questions about [course] design or something else, they can run that by the mentor or bounce ideas off of them about teaching.

“The feedback that I got from my mentees was that the best part of the program was having someone to support you.”

Certificate program a ‘unique and rare opportunity’

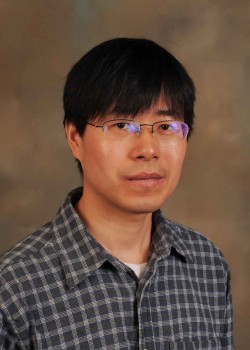

Chuang Deng says the program’s in-class observation and mentoring allowed him a safe space to work on improving his teaching.

Chuang Deng, an associate professor in the Faculty of Engineering who was part of the first cohort, agrees. He says in-class observations and work with his mentor allowed him a safe space to work on teaching areas he was most concerned about.

He calls the program a “unique and rare opportunity.”

When he started as an assistant professor in 2012, he didn’t feel that the hours he spent on the teaching paid off. Below-average Student Evaluation of Educational Quality (SEEQ) scores, some negative comments, dropping class attendance and pacing problems sapped his confidence. He felt he needed some formal training.

After enrolling in the program, his SEEQ scores increased significantly to above-average in his faculty, he notes. Anyone with a strong commitment to teaching could benefit from the program, he says — from those “who may have been struggling to deliver a lecture effectively” to those who wish to improve SEEQ scores.

The demands of teaching: ‘Backstage there is more to do’

Jean-Eric Ghia found the live observation of teaching to be helpful but tough, too. He says he joked with other cohort members, “Why at our age did we agree to give a course in the presence of a person in our class who is [evaluating] the good, the bad and the ugly of our teaching lesson?”

He admits it’s not easy to make oneself vulnerable like this, but calls the feedback he received “invaluable” Overall, he says the program allowed him to gain a legitimate confidence in his teaching skills.

Teaching is highly demanding, he says now. “What we see during the class is like what we see during [a] play, forgetting that the hours in front of the students or the public are only the tips of the iceberg. Yes, backstage there is more to do!”

That includes learning about novel and updated teaching techniques; creating and updating teaching philosophies; and adding new technologies to one’s repertoire, he notes.

“I learnt the basic ways of learning, the different teaching philosophies, the theories behind teaching practices, how to construct a rigorous lesson plan, and how to create a syllabus,” he says. The program boosted his teaching skills and confidence, and he’s since been recruited by the International Network for Educational Development and Scholarship in the Biosciences and is co-authoring an article with Francis Amara, biochemistry and medical genetics professor at the U of M, entitled, “Effective Engagement in Tutorials: Evidence-based-learning.”

Like his cohort colleague Chuang Deng, he recommends the program to not only all new faculty members — but any faculty at all.

Find out more about the Teaching Learning Certificate program at the Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning here.