Learning from the stars, and our backyards

Experiential learning is more than career preparation, it’s life preparation

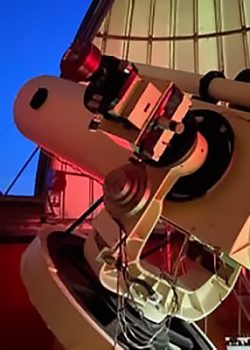

If the sky is clear on a class night, there’s a good chance you’ll find Danielle Pahud and her first-year astronomy students at the Glenlea Astronomical Observatory (GAO), about 20 km south of the Fort Garry campus. As her students figure out how to operate telescopes, make celestial observations and collect data, they’re also gaining some valuable lessons about life.

Photo by Kira Coop

“My students learn how to identify what they need to achieve their objectives, and to assess and take advantage of the tools at their disposal,” explains Pahud, an instructor in the department of physics and astronomy.

“I encourage my students to start with a goal in mind and, for this course, that involves choosing a scientific question to answer. We then take the time to learn about what observations we need to answer that question, and plan an approach and schedule to attain that goal.”

Experiential learning is often associated with co-ops and work placements, with a focus on making students “job-ready.” But, as Pahud demonstrates, experiential learning is more than career preparation. It is life preparation.

The Glenlea Astronomical Observatory. // photo courtesy of Danielle Pahud

“Things don’t always go as planned–between the weather and quirks with the equipment,” Pahud adds. “So, troubleshooting, creative problem-solving and even re-evaluating goals are part of the course, all of which translates into useful life skills. Plus, they’re often working as a group, so it gives them some real experience working collaboratively with peers.”

A piece of astronomy equipment aimed at the night sky.

At its core, experiential learning is when students learn by doing, and then reflect back to make meaning from what they just learned. Students put into practice their course content, finding ways to apply theoretical concepts in the real world and deepening their learning along the way.

Experiential learning teaches students a variety of life competencies that support them to become more adaptable and resilient in a changing world. It helps students to advance their personal growth and build professional and community connections. This year, as many students are returning to in-person learning, experiential learning also enables students to make new friends and explore new spaces.

The University of Manitoba has a long history of using experiential learning as a pedagogical tool. It views the learning environment as seamless, spanning both formal and informal learning spaces. It supports a broad definition of experiential learning that includes both curricular and co-curricular experiences.

UM also recognizes that experiential learning integrates principles drawn from Indigenous pedagogies, and is inextricably linked to Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing.

A still image from a video of Brian Rice and students launching a canoe.

Brian Rice is a member of the Mohawk Nation and a professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management. He is a land-based educator who has visited Indigenous peoples in many places in the world, and works to integrate experiential learning into his undergraduate and graduate courses.

“Instead of being stuck in classrooms for hours, I wanted my students to experience the actual places where Indigenous history and culture happens.”

“I’d been teaching Indigenous issues for about 26 years when I realized I wanted to approach things differently,” says Rice. “Instead of being stuck in classrooms for hours, I wanted my students to experience the actual places where Indigenous history and culture happens.”

Among other things, Rice has taken students canoeing along the Red River so that they could experience what voyageurs and Indigenous Peoples had been doing for centuries. He’s received permission from an Elder to conduct a sweat lodge for his students and has built snow shelters with them on the university’s agricultural land. Rice has organized overnight camping trips, waking students up at 5:30 am so they can experience the sunrise firsthand and discuss the Indigenous history surrounding them.

The Assiniboia Residential School, as seen in modern day. // photo courtesy of Brian Rice

“We touch on many aspects of pre-colonial and post-colonial history,” Rice explains. “For example, we can go to the places where Métis were forced out of their homes or to the Assiniboia Residential School, which is still there. We can walk down Wellington Crescent, where there are sites that are more than 3,000 years old, and imagine the Indigenous people who lived there and what might have been important to them.”

Rice is especially fond of taking his students for long walks, going as far as 12 kilometers at a time. His passion for walking is not surprising, as he completed a 1,000-kilometre walk from Tyendinaga near Belleville, Ontario to Rochester, New York as part of his doctoral dissertation. His trek followed the Journey of the Peacemaker, which united the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca people into the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

“You don’t have to go 300 miles out into the wilderness to do experiential, land-based learning.”

Ideally, Rice likes to take his students to sites through wooded and natural settings, so they get to experience and learn about nature. “You don’t have to go 300 miles out into the wilderness to do experiential, land-based learning,” he says. “There are wonderful natural settings right here in the city and, because of the rivers, we have a lot of beautiful trails. In the winter, we can even snowshoe up Buffalo Hill at FortWhyte Alive to see the bison herd.”

A metal wayfinding plaque installed on UM's Fort Garry campus to point in the four cardinal directions. // photo courtesy of Brian Rice

Rice believes that one of the core benefits of experiential learning is that it encourages young people to be physically active and healthy. He’s also keen to leverage students’ own creativity and motivation to help them succeed.

According to Rice, “I’d have students who lacked confidence about teaching Indigenous issues and didn’t know where to get relevant information on the assigned topics. When I suggested they could do something artistic, such as a poem or song, their resistance evaporated and they found a way to excavate what they needed to know.”

Students building a snow shelter in heavy parkas. // photo courtesy of Brian Rice.

As a leader in experiential learning, UM encourages all faculty to leverage it as a pedagogical tool. The university has recently outlined six criteria and 12 types of experiential learning as a resource for faculty and staff. You can find the complete list of types of experiential learning on our website.

UM is also committed to providing students with access to more and different types of experiential learning opportunities across all programs. It recently launched UMConnect, the home for both curricular and co-curricular experiential learning, job postings and a number of faculty co-op programs.

TeachingLIFE

UM is a place where we prioritize an inclusive learning and innovative teaching environment, in order to foster a truly transformative educational experience. TeachingLIFE tells the stories of our ground-breaking educators and their impact on student success.

Learn moreOther TeachingLIFE articles

Difficult conversations in the classroom

Confronting controversy to lead to a less-polarized society

Learning from the stars, and our backyards

Experiential learning is more than career preparation, it’s life preparation

More from TeachingLIFE

About CATL

The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning is an academic support unit that provides leadership and expertise in furthering the mission of teaching and learning at the University of Manitoba.

Learn more about CATL