Experiential learning made easy

Small steps, big outcomes

If you were to look in on Alexa Hryniuk’s anatomy class for first-year medical students, you might be surprised by what you saw – people playing with plasticine.

“I know this sounds like something you would do in grade school,” says Hryniuk. “But once students build their own anatomical model, the light bulb goes off. It lets them take a difficult, hidden part of the human body and really understand it. Students can see how tight the spaces are between organs or how clinical issues can arise.”

Alexa Hryniuk is an assistant professor in human anatomy and cell science. She teaches anatomy and embryology to a wide range of health care providers, including midwives, physician assistants and medical students.

And when it comes to teaching, she knows what she’s doing. Hryniuk has been nominated twice for teaching awards by the Manitoba Medical Students’ Association and has been researching medical education since graduating with her PhD in 2015.

Much of her success has been a result of integrating experiential learning, whereby students “learn by doing” and reflect on the experience. This approach supplements more traditional ways of teaching anatomy, using lectures, diagrams or cadaver dissections.

Micah Grubert Van Iderstine is a first-year medical student who was part of Hryniuk’s anatomy class using plasticine to study women’s reproductive health.

“Building the female pelvic region by hand really helped me to visualize it,” explains Van Iderstine. “In our traditional cadaver-based learning, we’d just see two ends of something sticking out from behind other structures and have to imagine its complete structure. I also thought it was a fun team-building activity, as we were all asked our opinions on where we thought certain pieces should be placed and the process encouraged us to question our own ideas.”

Hryniuk emphasizes the importance of developing activities appropriate for the student’s level of understanding. “You need to tailor the experiential learning model to the group you’re teaching. You don’t want to overload them,” she explains.

When teaching radiology to her first-year medical students, Hryniuk gets them to try an ultrasound machine for the first time. Or, she’ll have them look at a couple of really simple radiology images and try to identify the injury or disease.

“For first-year students, I’m trying to get them to look at clinical scenarios from different angles — just like detectives,” says Hryniuk. “This helps them become really good critical thinkers, which is what we want.”

When teaching diagnostic imaging and anatomy to her fourth-year medical students, she uses a more sophisticated experiential learning approach. For example, students might perform an ultrasound on their own shoulder and, if they see something like a ligament tear, they might go on to describe where to put the transducer to get the best visualization of the anatomical structures.

Hryniuk also shows these students various patient radiology images to see if they can describe the injury or disease, such as a bone fracture or a lump indicative of cancer. She’ll ask the students if they can describe what’s happening in anatomical terms, as well as what the patient is presenting with and what then needs to happen for treatment.

“This way, students are more prepared to serve their patients,” explains Dr. Hryniuk. “And they love this approach — they want more of it. They’re really keen to use the technology and relate it back to their patients.”

“…Students are more prepared to serve their patients, and they love this approach — they want more of it.”

Catherine Robbins, professor in choral studies and music education, also teaches anatomy. But for her, it is a tool to help her students improve how they teach and perform music.

“How we make sound is incredibly complex,” explains Robbins. “So an understanding of the underlying mechanisms is key to learning to teach and developing exercises for the voice. Students need to understand the physiology themselves and not just copy what someone else says.

“From the beginning of a course, I get out the skeletons so students can get a sense of who they are in their body. They explore the size, weight, and function of different body parts and joints, and figure out the best way to develop a dynamic posture and alignment.”

This focus on how the body functions provides the foundation for Robbins’s classes, which have experiential learning at their core. It is this approach that has won her rave reviews from her students, as well as a Merit Award in Teaching from the University of Manitoba in 2016.

For example, in Robbins’s choral conducting class, she divides the classroom into small groups, with each member taking a turn “conducting” the others. In this way, students give and receive feedback about their gestures, the movement of their joints, the quality of their stance or whether they’re breathing with the cues.

According to Robbins, “The challenge of teaching conducting is that they can’t actually practice with an ensemble until they begin their careers. Often, teachers will simply model the movement and ask them to copy it. Instead, I try to give students as much podium time in front of others who respond to them even if it is only one other person. The hope is that by the end of the course, they’ve better prepared themselves to stand in front of an ensemble.”

Robbins’s recommendation to professors in any field is to integrate experiential learning into the classroom immediately. She also believes that the reflection aspect of experiential learning needs to be well thought out and meaningful. Robbins will often get her students to record a video of themselves, review it, record their own feedback, and then discuss a short personal lesson with Robbins regarding how they can improve.

“It’s not enough to simply ask students to write down their reflection, it must be specific and meaningful,” says Robbins. “Once they leave the university, they’re going to need to consistently reflect on what they’re doing to work at their vocal teaching and conducting. I believe meaningful reflection builds the foundation for lifelong learning.”

“I believe meaningful reflection builds the foundation for lifelong learning.”

Hryniuk also offers some sage advice about bringing experiential learning into the classroom. “It doesn’t have to be complicated,” she says. “When I was teaching muscle groups, I had them use their muscles to move around the room or throw something. And don’t be afraid to fail. If something doesn’t work, ask your students for feedback. They’re very perceptive. They’ll let you know what went wrong.”

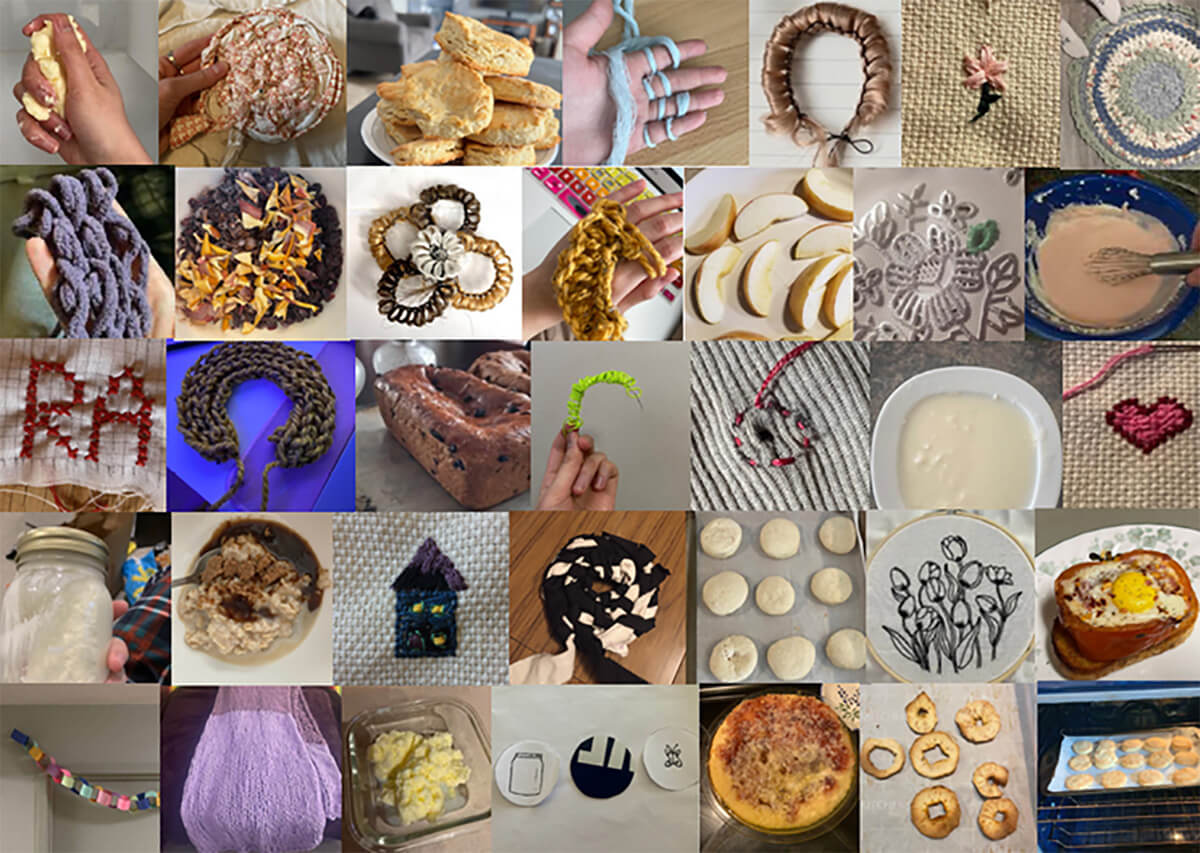

Bringing experiential learning into the classroom can be as simple as finding a more hands on way to approach a lesson. Two Faculty of Arts professors, Dr. Sarah Elvins and Dr. Vanessa Warne, found a unique way to approach the topic of domestic work in their joint History-English course. Instead of simply reading about it, they had the students actually do nine hands-on projects in domestic work, including butter churning, rag-rug making, embroidery, and cooking Victorian recipes. Students then critically reflect on how their knowledge of the physical work involved in these projects contributes to their understanding of the topics they are studying in their class and through readings.

The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning is offering a workshop titled: Who’s that in the mirror? Turn Experience into Learning through Critical Reflection on August 23 at 1:00pm. Sign up for the workshop and stay tuned for future options, including a workshop titled Getting Started with Experiential Learning.

TeachingLIFE

UM is a place where we prioritize an inclusive learning and innovative teaching environment, in order to foster a truly transformative educational experience. TeachingLIFE tells the stories of our ground-breaking educators and their impact on student success.

Learn moreOther TeachingLIFE articles

Difficult conversations in the classroom

Confronting controversy to lead to a less-polarized society

Learning from the stars, and our backyards

Experiential learning is more than career preparation, it’s life preparation

More from TeachingLIFE

About CATL

The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning is an academic support unit that provides leadership and expertise in furthering the mission of teaching and learning at the University of Manitoba.

Learn more about CATL