Reclaiming Anishinaabe Law

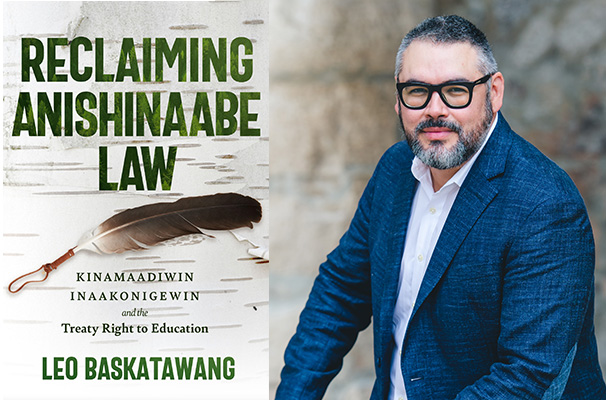

Dr. Leo Baskatawang publishes first book on Kinamaadiwin Inaakonigewin and the Treaty Right to Education

The publication of a first book is a rite of passage for many academics but making it accessible to the general public is a very generous and sincere way to share knowledge. Dr. Leo Baskatawang will meet that milestone of his academic career when the University of Manitoba Press releases his book Reclaiming Anishinaabe Law: Kinamaadiwin Inaakonigewin and the Treaty Right to Education on March 31, 2023.

An official launch of the book will take place at McNally Robinson Booksellers on Wednesday, April 19 at 7:00 p.m. with host, James Daschuk.

Baskatawang is an Anishinaabe scholar from Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation in Treaty #3 territory. He graduated with a PhD in Native Studies from the University of Manitoba in 2021. There, he taught online courses, and went on to hold an appointment in the Law and Society Program at York University, where he taught the courses “Indigenous Peoples and Law” and “Social Justice and Law.” Since joining the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Law at Robson Hall in 2022, he has taught “Indigenous Methodologies and Perspectives” to upper year law students along with colleagues Marc Kruse, Indigenous Legal Studies Coordinator, and Assistant Professor Daniel Diamond. He also teaches “Introduction to Law and Society,” and “Oral History, Indigenous People and the Law.”

Baskatawang’s primary research interests include: the processes of colonization, reconciliation, and decolonization; social justice; the history of Indigenous peoples (with particular attention to the Anishinaabe); Indigenous law and Canadian policy; treaty interpretation and implementation; Indigenous education; Indigenous resistance and activism; as well as Indigenous literature, art, and representation.

His SSHRC-funded doctoral dissertation “Kinamaadiwin Inaakonigewin: A Path to Reconciliation and Anishinaabe Cultural Resurgence” reflects on the development of the Treaty #3 Anishinaabe education law as it is known in the oral tradition, into a written form of law. As he explains in the following interview, this dissertation was the inspiration behind his new book.

In Reclaiming Anishinaabe Law Baskatawang traces the history of the neglected treaty relationship between the Crown and the Anishinaabe Nation in Treaty #3, and the Canadian government’s egregious failings to administer effective education policy for Indigenous youth—failures epitomized by, but not limited to, the horrors of the residential school system.

Rooted in the belief that Indigenous education should be governed and administered by Indigenous peoples, the future Baskatawang envisions is hopeful for Indigenous nations where their traditional laws are formally recognized and affirmed by the governments of Canada. He details the efforts being made in Treaty #3 territory to revitalize and codify the Anishinaabe education law, kinamaadiwin inaakonigewin. Kinamaadiwin inaakonigewin considers education wholistically, describing ways of knowing, being, doing, relating, and connecting to the land that are grounded in tradition, while also positioning its learners for success in life, both on and off the reserve.

As the backbone of an Indigenous-led education system, kinamaadiwin inaakonigewin enacts Anishinaabe self-determination, and has the potential to bring about cultural resurgence, language revitalization, and a new era of Crown-Indigenous relations in Canada. Reclaiming Anishinaabe Law challenges policy makers to push beyond apologies and performative politics, and to engage in meaningful reconciliation practices by recognizing and affirming the laws that the Anishinaabeg have always used to govern themselves.

What was your motivation for writing this book?

The motivation for writing this book was inspired from my doctoral research. I initially intended to write my dissertation on the Canadian government’s failure to adequately implement the treaty right to education. However, the focus of my research shifted when I learned about the Grand Council Treaty #3’s desire to codify a Treaty #3 Education Law. Being that the Canadian government has historically failed to develop an education policy that is respectful of Indigenous cultures, it seemed to me that having them recognize and affirm the authority of Indigenous nations’ own laws on education was a good way to test the government’s commitment to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s “Calls to Action” and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Who should read this book?

This book was written with the intention of being immediately accessible to all Canadians, whether they are Indigenous or not. As such, I hope the information I provide in the book will be of interest to government officials, policy makers, community leaders, educators, administrators, and students of various disciplines, including law, education, history, political science, and Indigenous studies, as well as to those conducting research on the processes of reconciliation and cultural resurgence. As I say in the book’s introduction, if my book can help to advance any of these matters in the glorious pursuit of social justice, all the better.

What do you most hope readers will take away from this book?

I think there are two important overlapping principles to take away from the book. One is that Canada has a long history of neglecting the treaties it signed with Indigenous nations, which is exacerbated by imposing policies on Indigenous peoples and communities that have been extremely harmful to their overall health and well-being. The second important message of the book is that all Indigenous nations have their own laws and governance systems that are capable of designing policies for the betterment of their communities and people. These laws and governance systems are formally recognized by UNDRIP, and need to be recognized and affirmed by the Canadian government as well.

What gap in knowledge do you know will be filled with this work?

The fact that Indigenous nations have their own laws and governance systems is only beginning to be recognized by Canadian society in general. This awareness is growing, due in large part by the work of Indigenous legal scholars such as John Borrows, as well as cultural resurgence scholars such as Leanne Simpson and Glen Coulthard. My research builds on the work of these scholars, with the hope that it will be useful to other scholars, as well as community leaders who have an interest in developing laws and policies that will better serve their nations and people.

To what extent can the information in this book be used to help communities in other Treaty areas?

I am conscious of the fact that my research is primarily dedicated to the people of the Anishinaabe Nation in Treaty #3. In the book, I am careful to consider that every Indigenous nation, or community for that matter, has different needs and interests that relates to education. That said, I hope the information that I provide in the book will be relevant to any Indigenous government that is considering undertaking a process of codifying some of its laws, particularly those that relate to education, since as I previously mentioned, Canadian education laws and policies have not adequately served Indigenous nations as they ought to.

What research project will you next be working on?

I am currently in the process, with the help of a few colleagues, of developing an annual volume of the Interdisciplinary Journal of Indigenous Inaakonigewin, in association with the Manitoba Law Journal. As part of this process, we are looking to recruit, both early-career and established scholars, community leaders, Elders, and artists, who have knowledge to share on how Canadian laws and policies can be amended to better serve Indigenous communities and people. Such knowledge mobilization is an integral part of the reconciliation process, and will be reflected in our journal in the form of academic papers, interviews, and artistic expression. In addition to the journal volume, my colleagues and I, are also planning to host an annual conference at the University of Manitoba which will be open and accessible to all, where these ideas can be shared, discussed, and included as part of our journal.