How does sleep help rewind the body’s clock?

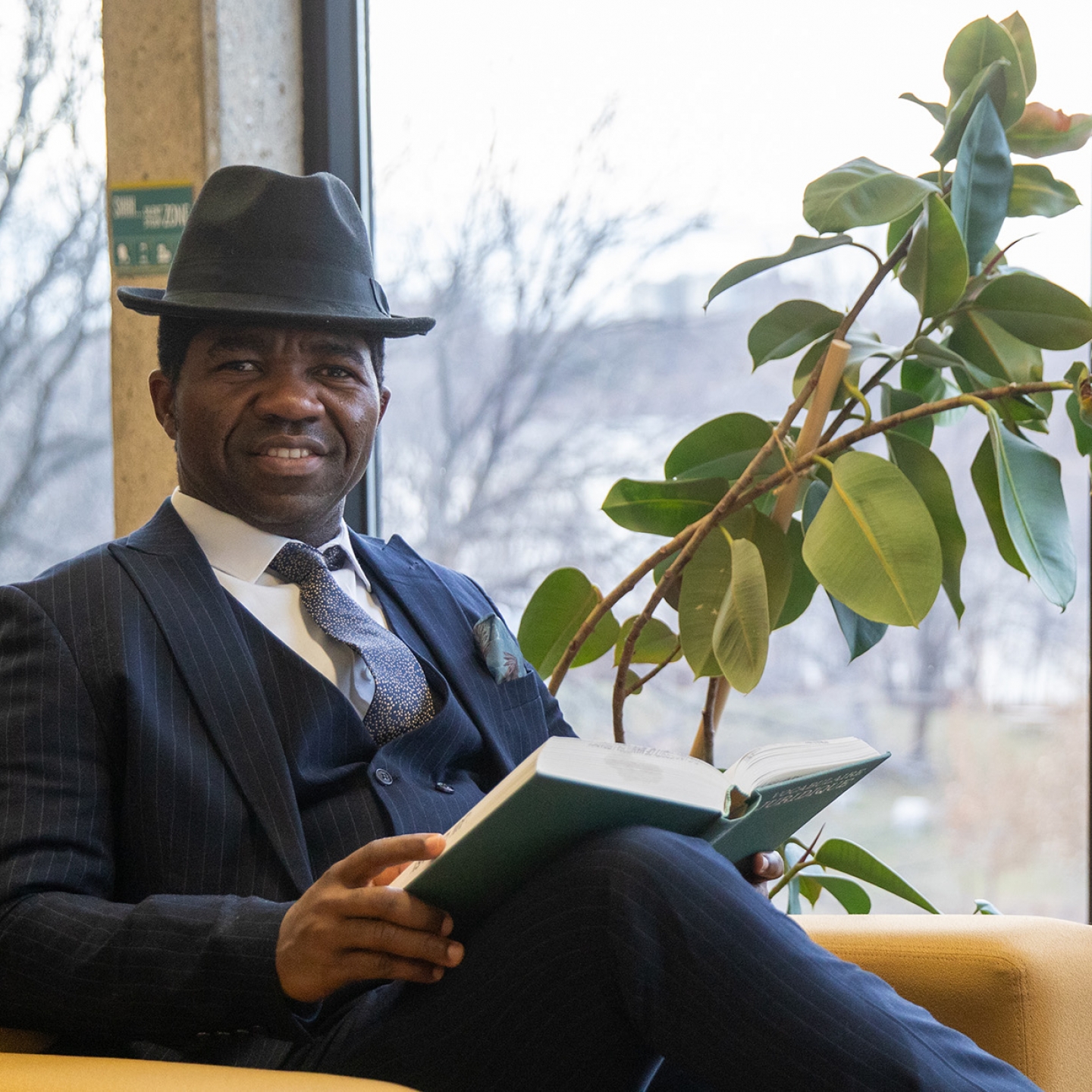

We asked heart expert Dr. Lorrie Kirshenbaum, Director of the Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences at St. Boniface Hospital.

-

UM continues to be recognized as a leading research-intensive university

-

Acclaimed production designer and alum Mary Kerr tells us how UM shaped her artistry and why she thinks contemporary theatre has lost its essential...

-

As climate change melts sea ice in Manitoba’s subarctic, northern communities explore Churchill’s future as a shipping route connecting the province...

-

When do employers cross the line? UM’s Jae Yun Kim tells us how to do the right thing in business.

Research

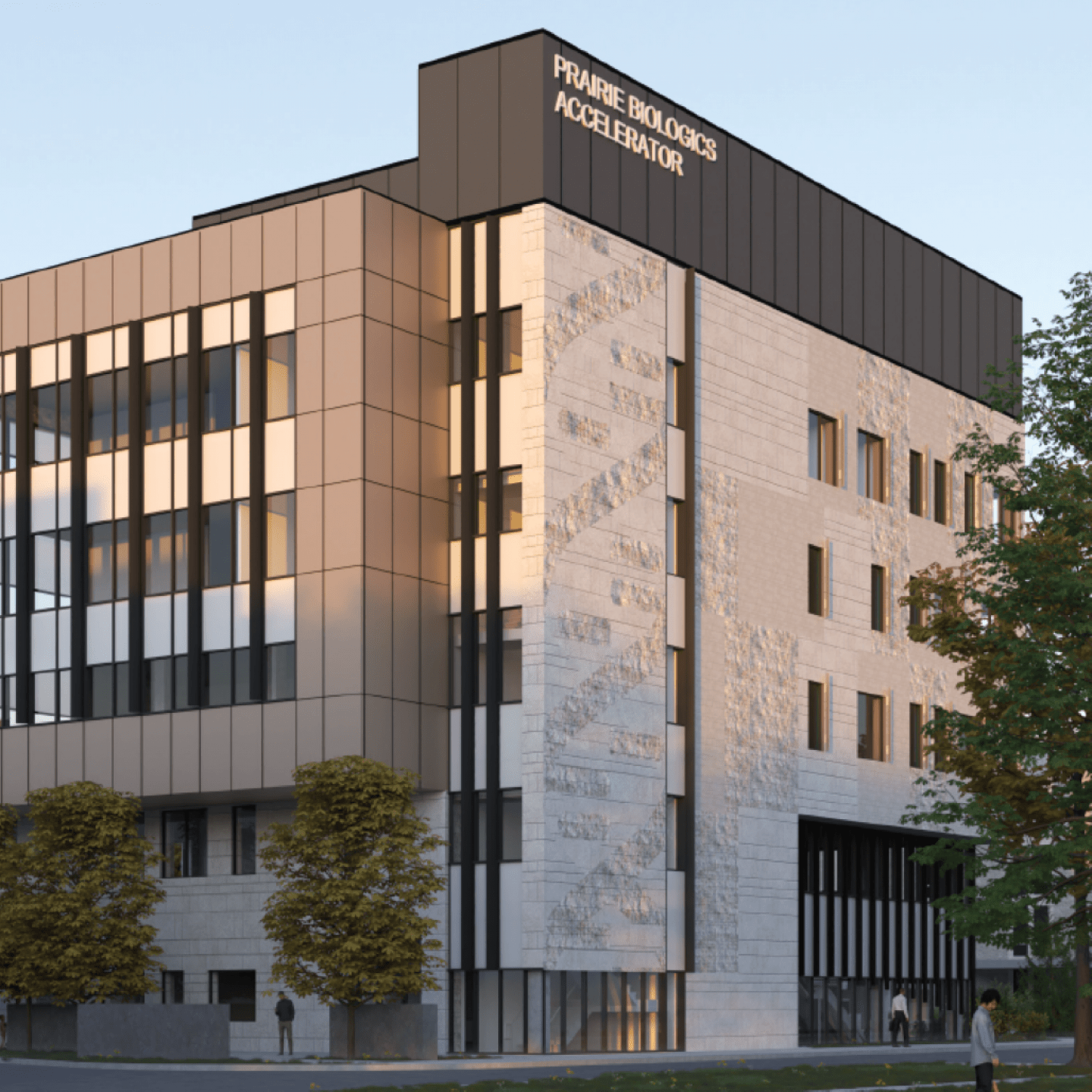

New 21,00 sq ft facility will advance vaccine research and biomanufacturing

-

Genetic diversity holds the key to climate resilience

-

Supporting stronger starts for infants, mothers and communities – especially in First Nations.

-

A new cutting edge in disease prevention.

-

Teaching and learning

The Faculty of Law's Northern Externship with Legal Aid Manitoba offers a rare and valuable experiential learning opportunity

-

Dr. Jocelyn Thorpe is awarded with the prestigious UM Teaching Excellence Award.

-

Celebrating teaching excellence at the College of Pharmacy

-

-

Alum Nathan Maertins shares his experience on a real-world project during his Asper MBA.

Indigenous

Honouring Louis Riel's sacrifice and legacy

-

Access Program and the Faculty of Education announce Hoka Canku – the Blue Heron Pathway to Education.

-

UM Chancellor Dave Angus sits down with the CEO behind Canada’s largest urban reserve.

-

Fireside Chats encourage Indigenous nurses to pursue graduate studies, take on leadership roles

-

Through UM’s Ongomiizwin Health Services, physicians travel to Manitoba’s northern and remote communities, bridging gaps and offering cultural care.

Students

Answering a calling to practice law

-

-

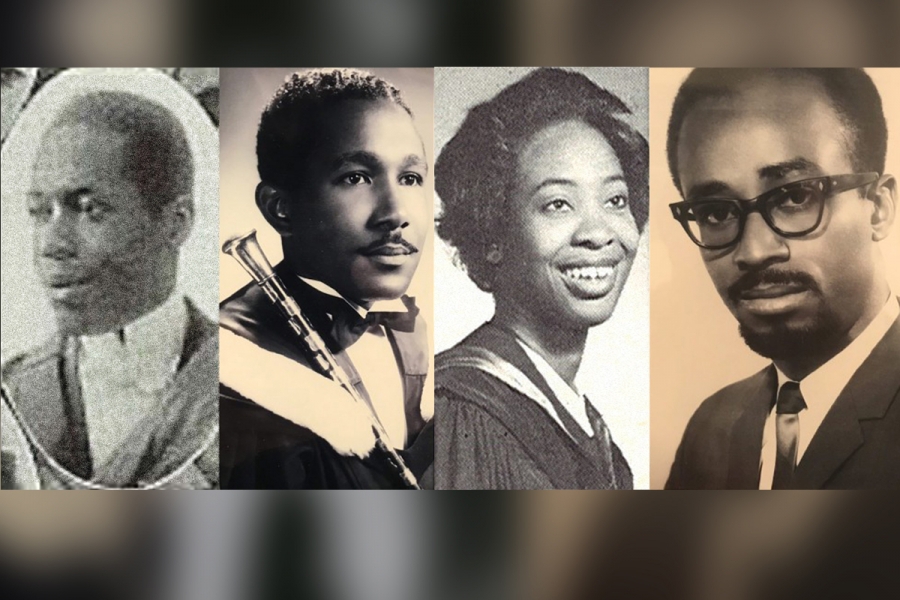

Celebrating the Black, African and Caribbean communities at UM.

-

Respiratory therapy student recalls ‘inspiring’ clinical experience

-

The Dean's Prize recognizes exceptional academic achievement, strong leadership skills and notable personal service.

Community

-

Ceremony held February 2, 2026 with flag flying through the month of February.

-

See what your former classmates are up to and tell us about your accomplishments. We welcome all updates!

-

Chancellor Dave Angus sits down with Winnipeg-based IT entrepreneur and UM alum Chris Schmidt for our new Bisons in Business series.

-

Indigenous artists offer connection, share stories and spark conversation through art.

News

-

UM continues to be recognized as a leading research-intensive university

-

-

The new publication provides a platform for thoughtful learning, critical inquiry, principled conversations and deliberate calls for action.

-

![Photo Collage by Kathryn Carnegie [BFA(Hons)/08] / Adobe / Getty Images A woman sleeping with an image of heart beats over her head](/sites/default/files/images/um-today-magazine-research-heart-health-collage%20%282%29.jpg)