Dr. Donn Short completes an important part of his research with the publication of his third book.

Making the Case for 2SLGBTQ+ student rights in schools

Law professor’s research aims to educate educators about religion-based rights claims

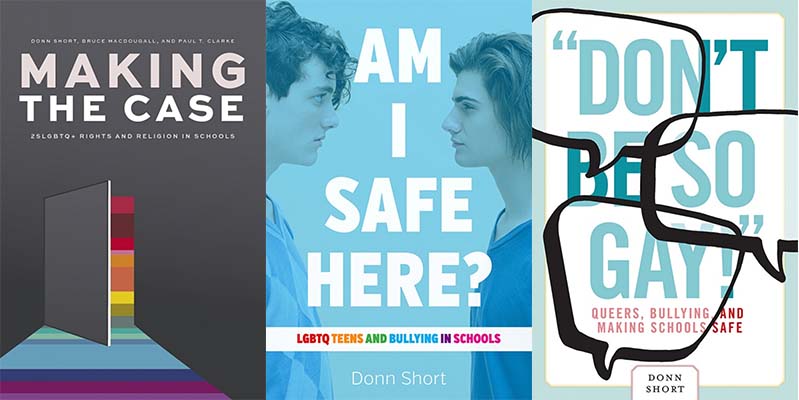

As the academic year ends, Professor Donn Short, Associate Dean of Research and Graduate Studies, spoke with Robson Hall regarding the publication of the third book in a series of volumes that concludes 15 years of his research. Making the Case: 2SLGBTQ+ Rights and Religion in Schools, released in November, 2021 by UBC Press in Canada and The University of Chicago Press in the US, rounds out a trilogy that includes Don’t Be So Gay! Queers, Bullying, and Making Schools Safe (2013) and Am I Safe Here? LGBTQ Teens and Bullying in Schools (2017).

This last book, written with educators, government officials and curriculum-makers in mind, was a collaboration with Drs. Bruce MacDougall (Allard School of Law, UBC) and Paul Clarke (Faculty of Education, University of Regina). Dr. Short is the founding and current editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal of Human Rights and a former member of the Manitoba Human Rights Commission. Robson Hall was able to catch up with him to learn more about this final portion of his current body of research.

What was your motivation for pursuing this area of research, and in particular this latest book?

With Making the Case, I wanted to produce a book that was empowering to people who were interested in or who are working towards supporting 2SLGBTQ+ students in their quest for equal access to education, full citizenship in schools, and creating schools that are places of inclusion for 2SLGBTQ+ students. This book is for those who may have been feeling un-empowered or insecure about what the law was around all that, particularly in the context of opposition based on religion-based rights claims.

I really wanted to put together a book that made it clear just how much support there was out there for anybody wanting to make schools safer and more inclusive spaces for 2SLGBTQ+ students. So, this book is meant to be empowering and encouraging to people doing this kind of work, that is, 2SLGBTQ+-inclusive education.

Who is this book for?

Teacher organizations, government workers including ministers of education, equity or human rights officers, curriculum directors or specialists, and local MLAs and MPs. Also School districts, super-intendents and trustees, and within schools, a school’s administration from principals to guidance counsellors to student councils. Outside schools, certainly parents, siblings, allies of every sort. With respect to teacher training, I think this book would be very useful to faculties of education, new hires, and especially for new teachers at all levels.

Finally, I’d love to see the book read by those working in faith-based schools: Catholic school systems – principals’ associations; trustees; Canadian Council of Catholic Bishops; the Ontario English Catholic Teachers Association; Edmonton Catholic Teachers (local 54 of the Alberta Teachers Association) and so on, other groups like that.

What is the main message in the book, Making the Case?

The main goal of this book is to empower people to understand what the law says or where the law is leaning. It’s not enough to say that something is against one’s religious beliefs or practices for it to be banned or forbidden: there needs to be objective evidence of that infringement. In the context of schools, if someone feels that a particular educational initiative infringes an individual’s or community’s expression of their religious beliefs or practices, then you have to prove it – it’s not enough just to say you think that it does.

There are some very basic concepts for law students, lawyers and professors. But I came to realize that “on the ground”, these concepts were not very well understood by many people. Of course, things can get much more complicated when you then move on to competing rights. Very often it is religious beliefs and declarations of infringement that are weaponized against 2LGBTQ+ equality rights. It seems to come as a shock to a lot of people asserting religion-based claims that their rights are not absolute – rights have limits – especially when those rights interfere with public safety or the rights and protection of other people.

So the second book looks at what teachers and the administration need to know when confronted with teachers or students or parents with religious objections to ensuring 2SLGBTQ+ rights for students in their schools. And at the time, this was during the years I think of as the GSA-wars, years of mounted resistance against gay-straight alliances, or gender-sexuality alliances, more often that not based upon the assertion of religion-based rights claims. I do want to stress, however, that there were many religious-based or affiliated groups who worked hard to support GSAs in their schools – OECTA, the Ontario English Catholic Teachers’ Association, for instance. It was the bishops and trustees who opposed GSAs in many cases. A lot of school boards and schools opposed them, too, but many were supportive.

How does Making the Case fit in with your previous publications?

The role of religion has filtered through all of my work to this point, the use of religion on the marginalization of these students. So I wanted to work on something that drilled down into that religious piece, which is this third book. The role of religion, the use of religious beliefs and practices to oppose or stymie equality rights – and what the law had to say about those kinds of claims, were themes that were present in both of the other books, and in many of my articles, in all of the research I was doing.

Making the Case confronts religion head on. The book was asking to be written. I asked Bruce MacDougall, who has written extensively about the legally-constructed queer child and law and religion, and Paul Clark, who has written a good deal about GSAs, to join me. But for me, it’s really the culmination of fifteen years’ worth of work.

The first book, Don’t Be So Gay! Queers, Bullying, and Making Schools Safe (2013), was very student-focused, looking at safety and inclusion from the point of view of students, treating them as experts of their own experiences, listening to and privileging what they had to say. This all started at the time when discussions around the country were about “safe schools” and “zero tolerance”, very punitive or response-oriented approaches. But the first book was the culmination of a number of years work that I undertook before the book was ready to be published and took things in a very different direction.

Early discussions about keeping schools safe took place at a time when school boards, safe school committee, parents viewed safety in terms of cameras, surveillance, guards in schools, zero tolerance policies. In other words, students were perceived as the threat to school safety. 2SLGBTQ+ students were largely ignored in that equation. The students I spent time with and listened to conceptualized safety very, very differently. They viewed safety very broadly, as a concept that included equality rights, safety as much more than just responding to bullying – safety that was really about the need to change the culture of schools in order to include and celebrate sexual minority students, to respond to heterosexism and homophobia and transphobia. So in this new conception of safety, students wanted the people who could make a difference to understand that heteronormativity itself in schools was the problem, the threat to the safety of these students.

The next phase of my work put more emphasis on teachers and how teachers could bring to life those aspects of making schools safe for students – primarily educative responses, the educative piece, the transformative piece, that would change the climate of schools. It’s that educative piece that ends my first book and is really the point of launch and the focus of my second book, Am I Safe Here? LGBTQ Teens and Bullying in Schools(2017). This was a question a student I met had posed to his school, to his teachers, his principal. What are you doing to keep me safe in this school? This book fit very nicely with other research I was doing at the time, that also focused on teachers and what teachers need to do to help 2SLGBTQ+ students achieve full citizenship.

I’m very happy to have these three books, and to have this as the last of the three because there is, for me, a sense of completeness to them, a sense of completion of 10-15 years of work.

What further work needs to be done in this area?

I think a study of religious schools, or people of faith at non-religious schools would be very, very useful – to really get that qualitative understanding of “why” – why do some people oppose this kind of work? Maybe even more interestingly, would be to look at the religious folks who support it, who don’t see their religious life, beliefs, practices as any kind of bar to, and at the same time, might even be pursuing, supporting 2SLGBTQ+ rights in schools. I think that kind of study would be very useful and empowering for other like-minded people. I do not think I will be the one to do it, however.

The final frontier (is anything final?) seems to be – and you see this right now in Florida – is getting past this idea that 2SLGBTQ+ inclusive-education is something that must be restricted to the higher grades. Listen, kids are already learning about sexual orientation – very largely negatively – in the early grades, as early as Kindergarten. The so-called “curriculum”, the unofficial ways students learn, through each other, sometimes from teachers, by listening to what the culture is already saying, they learn. At school, whether through sports, schoolyard conversations, all aspects of youth culture, really, are already “teaching” kids what to think about 2SLGBTQ+ students or their parents. So, it’s really important that the “official” or manifest curriculum – all the official spaces of the school – are brought into play, to respond to the negativity of that unofficial but very real learning, to counter it. 2SLGBTQ+ students need to be welcomed and celebrated and included officially as full citizens of every school from the first grade to the moment of graduation just as they are often denigrated and excluded unofficially. And, of course, very often officially marginalized, as well. Justice and injustice vary according to the particular school.

What lessons do you most hope readers of Making the Case will take away?

The law is more supportive than people think, particularly when competing rights come into play. A rights claim made by one person will sometimes conflict, or appear to conflict, with a rights claim made by someone else. This can happen when a 2SLGBTQ+ student asserts the right to be free from discrimination which a teacher, or another student, complains violates their legally protected religious freedoms. If possible, the courts will try to accommodate both rights. Sometimes that is not possible. In such cases, the courts will then ask if the 2SLGBTQ+ rights claim infringes on the religion-based right in a significant way? If the answer is no, the religion-based claim will give way to the rights claim. In these scenarios – and the book is full of them – the law, more often than not, supports educational initiatives that are intended to target the discrimination of 2SLGBTQ+ students in schools, to ensure their safety and inclusion. The courts are very likely to find that it’s a reasonable limitation on religious rights to ensure equal and open access of schools by 2SLGBTQ+ students and that it’s harmful to these students if the initiatives are not in place. In other words, religious rights are not absolute. And connected to that is the requirement that evidence of infringement of religion-based claims must be affirmatively shown – your religion-based rights are not infringed just because you say they are.

So with respect to all of that, Making the Case makes that case. It explains in a very straightforward, understandable way what “competing rights” are all about, what the issues are and how they are often resolved in favour of supporting a broadened conception of safety for 2SLGBTQ+ students.

Looking back now, these three books seem very cohesive to me as a body of work that adds up to something. That’s why I think I have completed this part of my research life. It feels all of a piece. The work is not over, making schools better has not come to an end, but my contributions may have.