Sticks and stones

Sandy Hershcovis, Associate Professor & Head of Business Administration in the Asper School of Business, presented her views at Visionary Conversations. But UM Today asked her to share some of her thoughts ahead of the talk. And she gave them to us, even with footnotes.

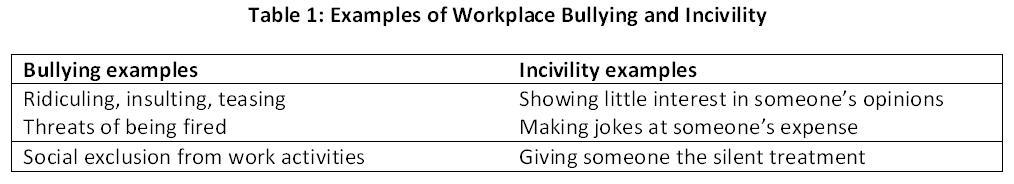

Workplace bullying is an unwanted negative behavior that is persistent, intentional, and is often perpetrated by someone who has either formal or social power over the target. Bullying is often insidious in that the perpetrator is able to undermine, threaten, and ostracize the target in such a way that the target is the only one who is aware of the victimization. In contrast, workplace incivility is a low intensity deviant act with ambiguous intent to harm the target[i].

Why should we care about workplace bullying?

Workplace bullying has human, organizational, and spillover costs. In terms of health costs, research has shown that workplace bullying affects salivary cortisol in victims[i], which is a physiological stress indicator. Victims may also display somatic health symptoms, including gastro-intestinal problems, headaches, and sleeplessness, all of which lead to greater sickness absences from work[ii]. Finally, recent research has shown that bullying victims are more likely than non-victims to exhibit symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[iii]. Given that PTSD is typically associated with major life traumas, this finding highlights the impact this type of behaviour can have on targets.

If the health consequences for targets are not enough to encourage organizations to take bullying seriously, then managers should consider the organizational consequences. Workplace bullying relates to lower performance[iv], lower creativity[v], more negative workplace attitudes[vi], and fewer citizenship behaviours[vii] for targets of such mistreatment. Further, to help regain a sense of control, targets often engage in counterproductive work behaviour by coming in late, calling in sick, stealing, intentionally working slowly, and engaging in more general interpersonal deviance towards supervisors and colleagues[viii]. In other words, the victims become perpetrators.

Perhaps most alarming is that when employees go home at the end of the day, the effects of workplace bullying do not remain at work. Instead, research shows that targets of workplace bullying are more likely to go home and undermine family members[ix]. Further, the spouses of victims report greater relationship tension[x] and stress[xi], suggesting that the negative health effects experienced by targets may transfer to their family members and may even damage marital relationships. These findings clearly show that workplace bullying spills over into the family domain.

But workplace Incivility is worse…

The above overview clearly shows the negative consequences of workplace bullying. So how could something as minor as workplace incivility possibly be worse? Recent evidence shows that workplace incivility has many of the same health[i], organizational[ii], and spillover[iii] consequences as workplace bullying, and that the magnitude of those consequences is the same.[iv]

There are two factors that make workplace incivility worse than workplace bullying. First, the prevalence estimate for workplace bullying is roughly 14%[v]; whereas, the prevalence estimate for workplace incivility is nearly 100%.[vi] Second, workplace incivility is not experienced equally by all members of the workplace. Instead, evidence suggests that perpetrators are more likely to target workplace incivility towards minority groups. In particular, women of colour and females are more frequently targeted than males (white or African American)[vii]. What this means is that workplace discrimination and sex-based harassment, which are illegal in Canada, have gone underground and workplace incivility is a new form of invisible or unseen discrimination.

Are we a Society of Bullies?

The above evidence suggests that the answer to this question is unequivocally, yes!

[i] Andersson & Pearson, 1999

[ii] Hansen et al., 2006

[iii] Nielsen et al., 2008

[iv] Nielsen et al., 2008

[v] Harris et al., 2007

[vi] Mathisen et al., 2008

[vii] Hershcovis & Barling, 2010

[viii] Harris et al., 2011

[ix] Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007

[x] Hoobler & Brass, 2006

[xi] Carlson et al., 2011

[xii] Haines et al., 2006

[xiii] Cortina et al., 2001

[xiv] Chen et al., 2013

[xv] Ferguson, 2012

[xvi] Hershcovis, 2011

[xvii] Nielsen et al., 2009

[xviii] Porath & Pearson, 2010

[xix] Cortina et al., 2011

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.