My, What Big Teeth You Have!

New Paper on Wolf-Beaver Predation Published in Respected Scientific Journal

For someone who grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, Ph.D. student Sean Johnson-Bice’s choice of studies might seem a bit surprising. Instead of studying architecture or business, Johnson-Bice is currently researching the Arctic and red foxes. Working under the supervision of Dr. James Roth in the Department of Biological Sciences, he says he’s always been drawn to nature; wolves in particular.

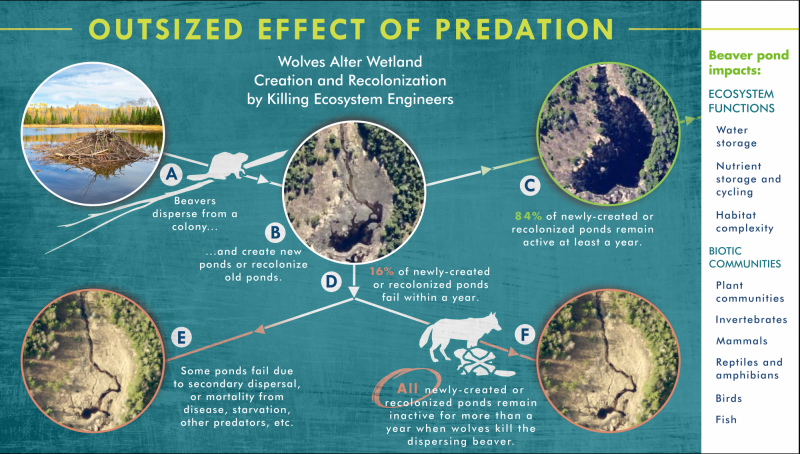

It’s satisfying then, that Johnson-Bice’s most recent research article on wolves has garnered him and his co-authors a spot in the American Association of the Advancement of Sciences’ journal, Science Advances. Entitled “Outsized effect of predation: Wolves alter wetland creation and recolonization by killing ecosystem engineers”, it summarizes the research done by Johnson-Bice and colleagues into the predatory behaviour of gray wolves on beavers, and how this interaction affects wetlands in and around Voyageurs National Park.

Johnson-Bice’s formal study of canid behaviour began in the spring of 2015 when he was hired as a biological science technician for Voyageurs National Park, in International Falls, Minnesota. Biologists at the park had been monitoring the wolf population since 2012 when gray wolves were first delisted from the Endangered Species Act. Initial efforts focused more on monitoring efforts — trying to understand such things as how many packs were in the park, the packs’ boundaries and how many wolves were in each pack.

In Fall 2016, Johnson-Bice started his studies at the University of Minnesota. His MSc research concentrated on the population and spatial dynamics of beavers in other regions of Minnesota. Since his MSc advisor (Steve Windels, a co-author on the wolf predation paper) was the head wildlife biologist for Voyageurs National Park, Johnson-Bice was able to stay current on the research, returning to work there during the summers of 2018 and 2019.

Called the Voyageurs Wolf Project, it is a collaborative effort between the University of Minnesota (led by Tom Gable, Prof. Joe Bump, and Austin Homkes), Voyageurs National Park (Steve Windels), and several other researchers including Johnson-Bice. The park has one of the densest beaver populations in the United States, with a rich history of beaver research dating back to the ‘80s. Johnson-Bice says the recent focus on wolf-related research is relatively new.

“The specific inquiries into wolf-beaver interactions started with Tom Gable’s work in 2015. It was definitely a struggle at first for all of us — no one had ever really studied wolf-beaver interactions before, so there was no blueprint about how to do it.”

Most current research on wolf-beaver interactions focuses on understanding the methods wolves use to hunt beavers, as well as the investigation of kill sites. This paper describes how wolves can alter pond creation by killing beavers. Although it wasn’t the original focus of the project, the publication of this study has made the question of how wolves influence wetland creation a major component of the long-term project goals.

Johnson-Bice’s contributions focus on understanding the ecological effects of wolf-beaver interactions and how this relationship affects boreal forest ecosystems. To date, very little research has been done on predator-ecosystem engineer dynamics. His work is amongst the first to evaluate this relationship in depth.

“Beavers are arguably the most prolific and widespread ecosystem engineers in terrestrial ecosystems, so they are an excellent model species to evaluate predator-ecosystem engineer dynamics.”

Beaver Carcass. Beavers reshape landscapes by building dams. But wolves prey on the ecological engineers, limiting where they live. Photo supplied.

That’s not to say that research into beavers is easy. The search for kill sites during the summertime is gruelling. The monitored wolves are fitted with GPS collars which record their locations approximately every 20 minutes. Johnson-Bice and his colleagues visited every place where a wolf recorded at least two GPS points within 200 metres of one another (spots commonly referred to as “GPS clusters”). Each day the team would load the GPS clusters onto their handheld GPS units, then bushwhack their way out to every such site. Johnson-Bice likens the work to that of a crime scene investigator.

“With small prey like beavers and deer fawns, the wolves will often consume the entire animal, leaving very little evidence of the ‘crime’ that occurred. Oftentimes we only find a tuft of hair, a couple of bone fragments, or maybe even a few drops of fresh blood, if you’re lucky. So at each cluster, we walk through it slowly and methodically, putting together these small pieces of evidence to determine whether a kill occurred there or not.”

In fact, the methods that the researchers developed for finding kill sites of these small organisms are so unique to the study that it is crucial to train new team members in their use. Each new technician joining the project gets put through a “boot camp” of finding kill sites.

Sean Johnson-Bice, University of Manitoba, PhD student.

While Johnson-Bice feels that the results of this study won’t be particularly surprising to anyone familiar with wolves and beavers, he has discovered something he finds intriguing.

“Wolves and other large predators are primarily thought to impact ecosystems by altering the abundance or behaviour of their prey, which can have cascading effects down the trophic levels. But in Voyageurs, our research suggests wolves do not kill enough beavers to affect their abundance. So the fact that we have convincingly shown wolves can impact wetlands without necessarily changing the abundance or behaviour of beavers is an exciting finding.”