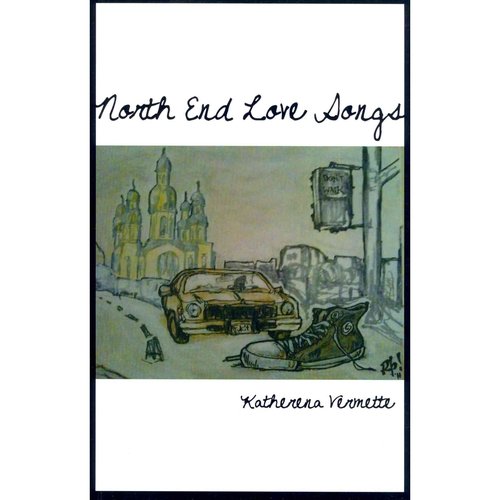

North End Love Songs.

CCWOC affiliate Katherena Vermette wins 2013 GG Literary Award for Poetry

Centre for Creative Writing and Oral Culture (CCWOC) affiliate Katherena Vermette is about to be awarded the 2013 Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry, for her collection North End Love Songs.

The born-and-bred Winnipegger, who is currently finishing her MFA in creative writing at UBC, wrote the poems in the book over a period of about ten years.

In the poems, Vermette was thinking back to her childhood and coming-of-age in North End Winnipeg. UM Today spoke to her the day before she boarded a plane for Ottawa to receive her award. The ceremony takes place November 28.

She struggled with her identity during that time, a struggle that reflected in her writing, she says: “living in an impoverished neighbourhood, being a bi-racial person in a world that does not always look positively on Indigenous people and culture.”

Much of the book focuses on the loss of her brother, who went missing on November 3, 1991, after his friends left him at the bar where they all had spent the evening. He had just turned 18.

The bar was across the river, says Vermette, and his body was found months later, in the lake north of the Grand Beach area.

The disappearance wasn’t taken very seriously at the time. “There wasn’t any discerning effort made to find him as a missing person. The assumption was that he was on a bender and because he was a young guy, that he was out partying,” she recounts.

Vermette says that she believes that “though we’re not defined by the trauma that happens to us, it becomes a part of us. We grow through it, we learn.

“[My brother’s death] really did shape a lot of my beliefs and my later reactions as an adult.”

The stories in her poems are also part of her cultural heritage.

Her self-described tendency to tell stories in her poems comes from her influences of Indigenous poetry, she says.

“[Indigenous poetry] has the other aspects of poetry, too, what we think of poetry today — rhythm, sound, images … but it also has this strong connection to the oral tradition.”

How did she develop that link between poetry and story in her own writing? According to Vermette, she’s always written that way.

In fact, she says, “I find there’s always a story in poetry; it’s just a little more evident in some poems than in others.”

Q + A with Katherena Vermette

What do you love most about writing poetry?

Poetry is like breathing. No one writes poetry unless they really love it. I really love it. I write other things, and they’re great and all, but poetry is the most organic for me. When poetry is going well, it’s like meditation, like that first sip of coffee, that first breath of winter air. And, when it’s going not so well, I still manage to remember that I love it anyway. That’s true love right there!

You mentioned that your book ended up being a bit of a coming-of-age story. How do you see the relationship between identity and writing, and poetry in particular?

I write poetry when I am confused. I write my way through things to articulate what I am thinking and feeling. Sometimes I looked back on a finished poem, and go “oh, that’s what that was all about!” This is how all art helps shape our identity. It’s one part catharsis, one part magic, and then a whole bunch of work that still manages to be fun.

Can you say something about the relationship of heavy metal music to this writing?

Heavy metal was a big part of that time in my life. As a kid I was a big headbanger, and my brothers — I had two older brothers — were headbangers, so it had a big part in our whole upbringing. So when I started thinking about this story and how I wanted to frame it, the music became a big part of that. I started listening to a lot of old stuff — the stuff my brothers listened to — Mötley Crüe, AC/DC, Skid Row.

Sound is like smell. You hold a lot of memories in the music you listen to.

It was great to immerse myself in that music, 20 years later, and then write through that.

In the book I talk a lot about heavy metal ballads, because as a 14 year old kid … you have an incredibly emotional experience with that. It was a really emotional place that I went back to.

When and how did you start writing?

As a kid. I was a sad kid. I remember my mom handing me a notebook and pen when I was about 10 and telling me that I should write things down, figure them out. My mom was an old hippie. I went to a lot of therapy as a kid as well, so it was really just a part of that whole cathartic process of figuring out my head.

As for poetry, I just always did it. You asked how I came to write this story in poetry, and I guess it was because I heard it that way. All of the rhythms came out in poetry. You have to listen to it; a poem will tell you what its rhythm is.

Who are the poets and short story writers you like to read and/or ones that have influenced your own writing?

Oh so many. My friends at the Indigenous Writers Collective for starters, particularly those who have been like mentors to me – Marvin Francis, Duncan Mercredi, and Rosanna Deerchild (a trifecta of Cree goodness). I’ve been working on my short fiction this past year, and have read a lot of Richard Van Camp, Annabel Lyon, and of course, Alice Munro. Jeannette Winterson is a dream, and I am certain that Maria Campbell and Beatrice Culleton Mosionier changed my life.

Do you consider yourself a prairie poet, and how does the landscape come into your work?

I’m very much a prairie girl and I love the whole farm/ocean/crop/sea thing — I love getting outside of the city — but I am a city girl. I like this town. I’m a river poet, definitely — and[rivers] are part of prairie poetry. It’s from an urban perspective; there are prairie cities.

Has the shock worn off? Have you done any proper celebrating yet?

I don’t think it has. I’m leaving for Ottawa tomorrow, and the week is going to filled with a lot of really intimidating Governor General-type stuff. It’s going to be a lovely party, I’m sure, but I’m kind of waiting until all of that’s done and then life will return to normal and we can properly celebrate.