The University of Manitoba’s is home to a 135-member sea-ice research group, the largest sea-ice focused research group in the world

U of M’s Arctic expertise sought by Senate of Canada

David Barber tells Senators to expect ice-free summer in Arctic by 2030

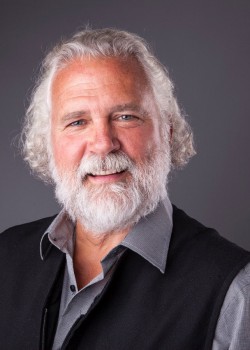

Distinguished Professor and University of Manitoba alumnus David Barber [BPE/82, MNRM/89] presented research findings to the Senate of Canada’s Special Committee on the Arctic on April 16.

The Special Committee on the Arctic is considering the significant and rapid changes to the Arctic, and impacts on original inhabitants and they asked for professor Barber to share his expertise with them.

Barber’s presentation, “The Global Implications of a Melting Arctic,” informed the special committee about the consequences of observed melt and climate change that’s going on in the Arctic right now. (Watch his presentation here, beginning at the 19:51 mark.)

Barber, Canada Research Chair in Arctic System Science, leads the University of Manitoba’s 135-member sea-ice research group, the largest sea-ice focused research group in the world. They have been doing research in the Arctic for over 35 years.

“We’re finding now very strong connections between what we call Arctic and mid-latitude teleconnections,” Barber told the Senators. “This is what we believe is responsible for a lot of the unusual weather that we’re getting at lower latitudes of the planet because we’re changing the shape and structure of the polar vortex. That is because we’re losing sea ice in the Northern hemisphere. We’re putting a lot more heat into the atmosphere, which changes the pressure patterns and, therefore, changes the polar vortex and our weather and climate at more southerly latitudes.”

At the end of Barber’s presentation, Senator Dennis Glen Patterson, chair of the committee, asked Barber about when we can expect an ice-free summer in the Canadian Arctic, particularly, the Northwest Passage.

Barber responded:

“Projections right now for a seasonally ice-free Arctic — so that means, you know, down to less than 10 million square kilometres of ice, which is really just kind of trace ice in the High Arctic — will happen somewhere around 2030. And when you think of that, it’s a complicated thing to think about, but the way ice moves around the northern hemisphere…you’ll see that most of the arrows are pointing towards the North American side. That means that the Northwest Passage will be the last of those passageways to open up.

You have three major transportation corridors across the North Pole. The one that goes along the Russian side is called the northern sea route and it is already open and the Russians are actually using it year-round right now to move natural gas in liquefied form between Asia and Russia.

The over-the-pole route, which is the middle one, has only been open since 2010 but only seasonally in the summer. That green one is the Northwest Passage that you see that goes through our Arctic Islands. It will be the last of those three routes to open. Then this red is one is the Murmansk-Manitoba bridge that we talked about that goes into the Port of Churchill in Manitoba, and it can connect to all of those transportation corridors bringing things out of the interior of North America. It’s an important bridge from our Canadian perspective because of the access to the rail system and getting interior to North America.

So we’re on a trajectory for a seasonally free ice-free Arctic somewhere around 2030 and the northern sea routes and passages are already opening up. That’s why we have to make sure we’re prepared for the kinds of things that can happen.

To give you one example, even if Canada has closed down oil and gas exploration in Northern Canada, the Russians are developing their oil reserves on the Russian side of the Arctic right now. To give you an idea, Russia generates about 26 per cent of its GDP from the Arctic. We in Canada generate a fraction of 1 per cent of our GDP from our Arctic, yet it’s the same Arctic. It has the same resources and same everything. We just don’t have the built infrastructure to be able to do things in our own Arctic.

From my perspective, we need to develop our Arctic. We need to prepare for the future. It will become much more accessible and between the Inuit who live there and the scientists who study it, we need to come up with better information so we can manage it better.”

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.