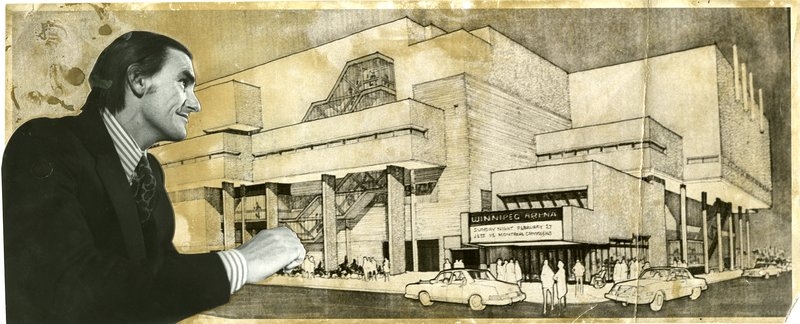

Architect John Turner admires his 'new look' arena in 1979 after he added some enhancements, like escalators. // Image from U of M Libraries Digital Collections

The price of ice and the cost of hockey

The following post is from Hockey Night in Headingley, a new(ish) blog created by University of Manitoba economics professors and hockey parents, Ryan and Janice Compton.

As the Comptons write in their inaugural Oct. 16, 2013 post introducing themselves:

“Janice spends most semesters teaching large classes in first year microeconomics where hockey examples tend to be class favourites, while Ryan frequently offers a course in sports economics with a significant focus on hockey. With the recent return of the NHL to Winnipeg, coupled with our boys playing hockey most months of the year, hockey and economics is a frequent topic in our household, and we hope this blog will be a place to give our thoughts as well as learn a thing or two ourselves.”

The two also come clean about their own biases: “Janice is a Boston Bruins fan, while Ryan is a St. Louis Blues fan!”

The price of ice and the cost of hockey

The Globe & Mail series on the effect of inequality on our communities and aspects of our daily lives is quite interesting. In one article, James Mirtle writes that inequality has impacted the ability of many families to enroll their children in hockey. I have previously blogged about the impact that inequality may have on the costs of hockey, and noted that the provinces with the highest levels of inequality have the lowest participation rates in minor hockey.

However, I disagree with Mirtle on the ‘obvious’ solution to spiraling costs – subsidizing arenas and ice times. This changes the price of hockey, not the cost of hockey. In fact, it’s not improbable that such interventions could lead to an increase in the average amount spent on minor hockey.

The G&M article laments both the amount required to play elite hockey, and the amount required to play at lower levels of competition. I’m more interested in enabling families to enroll their children in hockey just for fun. I’m not convinced that competitive hockey is that much more expensive than other competitive activities. I have one niece who plays year-round competitive soccer, another who is involved in competitive Irish dancing and a nephew who plays elite baseball. The amounts spent on these activities are comparable to what we spend on competitive hockey. So why the continual focus in the media on the spiraling costs of minor hockey? I believe the differences is that, unlike these other activities, it is becoming too expensive to even play organized hockey just for fun and this strikes some as simply un-Canadian.

We also need to be clear on the difference between the costs of playing hockey and the amount spent on hockey. The G&M article quotes the average amount spent. If we are concerned with enabling children to play hockey (as opposed to enabling children to play elite hockey) then the important figure is the cost necessary to play the game. It is quite possible to outfit a child for hockey for a couple of hundred dollars, and to play only the regular Hockey Canada season. If your team practises once a week and does not travel to out of town tournaments, the overall cost can be comparable to other activities. The average amount spent is higher because many children and their parents want to play more often and participate in out-of-town tournaments, and this leads teams to raise the price. Outside the regular season, many families also invest more time and money in better equipment, training camps, spring hockey, power-skating, 3-on-3, dryland training, etc. etc. The teams practise more because other teams practise more; players engage in additional training because other players engage in additional training. Economists would explain this over-investment in hockey using either labour economic theory or basic game theory.

Like all sports, success in hockey is relative. You don’t need to be good to win the game, you need to be better than the other team. To make the competitive 9A1 team, the AAA spring team, the WHL, the NCAA or the NHL, you don’t need to be a great hockey player. You need to be greater than everyone else competing. While this is true in most sports, I would argue that, in Canada, the gap between the reward for making it versus the reward for just missing out is much greater in hockey, both at the top levels (consider the gap between the NHL and the AHL*) but also at minor hockey levels. Kids idolize hockey players, and this filters down so that the 13-year old who plays AAA hockey has quite a bit of swagger walking around in his team jacket, perhaps more so than his friend who is a competitive swimmer.

In labour economics, this is called a Tournament Model of Compensation. When the gap between the reward for the top level and the next level is very high, there is a strong incentive to invest work effort in the hopes of moving up. In fact, the model can predict that players not only invest in work effort, they over-invest. Vice-presidents of a company will work 100-hour weeks, trying to out-perform the other VPs in an effort to be promoted to the top spot. Similarly, kids will spend 10 hours a week at the rink, in the hopes of winning the city championship or grabbing a spot on the competitive team.

We can also model this as a repeated prisoner’s dilemma game in which players end up at the inefficient equilibrium of over-investing.

So the problem with subsidizing ice times is that this type of intervention lowers prices but does not necessarily lower costs. Since teams have flexibility in how often to practise and where to travel, the result of lowering the price of ice time could simply be more ice time. Similarly, providing grants to lower income households to cover hockey costs means more competition for the elite teams. This could result in the wealthier parents demanding even more ice time or additional training and the cost of being on the team could rise.

A solution that better fits the problem is one that introduces limits on the amount of training teams can purchase. In the types of models described, constraining behaviour can have a positive outcome. Hockey Canada could set the amount that teams could charge, or set a maximum number of practices, games and tournaments for the season. Granted, this would not eliminate the ability of parents to go outside the Hockey Canada program and so over-investment in hockey would still occur, but it would at least open up a base level of ‘playing for fun’ that currently may be difficult to find, especially in jurisdictions with high inequality.

JRC

*This isn’t to say the gap between the top levels in baseball, football and basketball are not high, just that they aren’t as popular or widely discussed as hockey.

Janice Compton is an assistant professor of economics and holds a PhD from Washington University.

Ryan Compton is an associate professor of economics and holds a PhD from Washington University.

The featured images above of the Winnipeg Arena are from the University of Manitoba Libraries new Digital Collections website. To see more images of professional hockey in Winnipeg, click here.