Near, though far

University of Manitoba statistics instructor Jenna Tichon’s students were thrilled to see their pets used as a teaching tool. And computer science instructor Robert Guderian set up virtual coffee hours, where students could talk about anything from coursework to geocaching.

Statistics instructor Jenna Tichon and computer science instructor Robert Guderian.

As the Faculty of Science instructors found novel ways to engage classes in virtual classrooms, they discovered remote teaching had made them even closer to their students. Rituals, familiar routines and building personal connections helped learners feel connected to instructors—and vice versa.

“Something that I had to do is make a point of showing more of myself and making sure that, even if you’re doing an asynchronous course, that your presence is felt as a person.”

“Something that I had to do is make a point of showing more of myself and making sure that, even if you’re doing an asynchronous course, that your presence is felt as a person,” says Tichon.

Guderian and Tichon shared their remote teaching experiences at a February teaching café run by the UM’s Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning (CATL).

Colleen Webb, CATL team lead in development and consultation, started the annual round-table teaching cafés in 2017 to share strategies and innovations across UM faculties. The COVID-19 pandemic pushed the 2020 café to February 2021. Three months later, a second café was held, focusing on incorporating Indigenous perspectives and knowledge into teaching.

“With the teaching café we really try and bring in a range of presenters from the different faculties,” says Webb. The small-group participants find inspiration and ideas from their peers, like the joint presentation by the Faculty of Arts and Desautels Faculty of Music involving interpretive dance for the session Dance Like Nobody’s Watching: Interdisciplinary Teaching and Learning in the Era of COVID. (read more about that here.)

Guderian says rituals are important to students. One he wanted to replicate for remote learning was the risk-free, informal discussions that typically break out as students leave a lecture. He started a virtual coffee time and told the students: “You can talk about whatever the heck you want.”

He started a virtual coffee time and told the students: “You can talk about whatever the heck you want.”

“And you can actually connect,” he says. “A lot of it was the students talking to other students and that’s something that they’ve lost.”

It was also beneficial for Guderian.

“The thing that I missed the most teaching was those the keen students that would come down and just talk to you after class. How do you find your future graders, how do you find your future lab TA, how do you find your future grad students? Those are the people who would linger after class,” he says.

Predictable things, like always following the same structure of recorded lecture followed by a real-time time class bring a calming sense of pattern. “It’s kind of comforting,” says Guderian. “They really need to be able to lean on something like that.”

Guderian teaches large classes. His smallest group is 65 people. Yet remote learning has made him feel more connected to learners. He feels like he’s sitting across a table from them now—when students have their camera on for virtual learning—rather than lecturing to people in rows of seats that stretch to the back of the room.

Chat functions have been a surprisingly useful tool, Guderian says.

“It’s amazing. Some students that would never ever, ever talk to me, I’ve actually built relationships with.”

“It’s amazing. Some students that would never ever, ever talk to me, I’ve actually built relationships with,” he says. Students who may be reluctant to speak in class are willing to express themselves in a chat function.

Engaging with students weaves through Tichon’s remote instruction. Before Fall Term classes began, she posted a letter, telling students about herself, her academic background and her hobbies. They now know she’s training for half marathon, enjoys playing Final Fantasy and usually has a knitting project on the go.

“Something that I had to do is make a point of showing more of myself. You’re making sure that your presence is felt and that your presence is felt as a person,” she says.

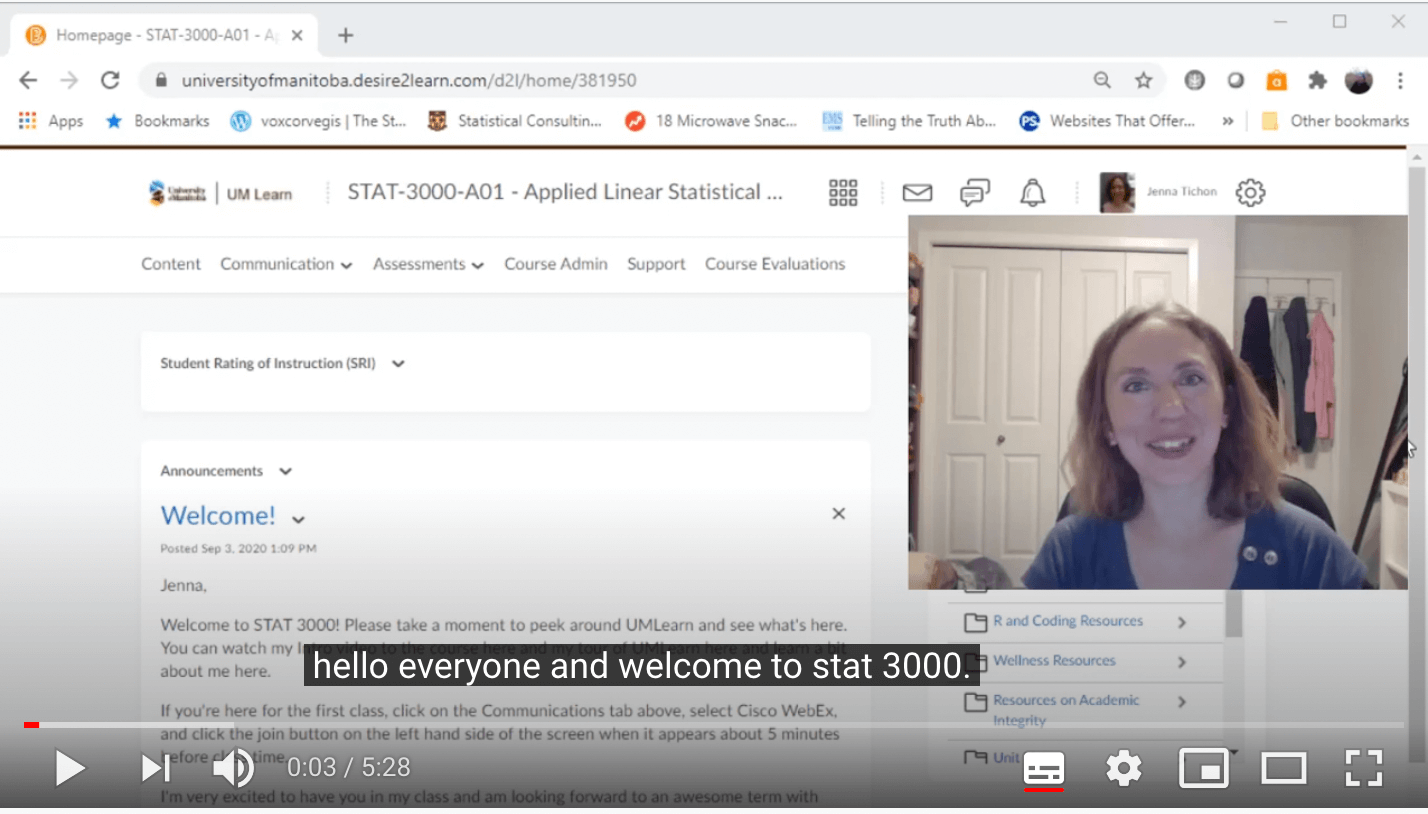

A screenshot of one of Jenna Tichon's online lessons.

Tichon’s first year student welcome video included a virtual tour of the university learning management system UM Learn, as well as where to find online tools like discussion posts and quizzes.

“I also took a moment to say I know this is a really crazy kind of scary time but we’re in this together. If you have problems, you have suggestions, please come talk to me. I’m here. This is an experience that we’re going to figure out together,” Tichon says.

Because she teaches hundreds of first year students, she wanted their initial university experience to be positive, one that extended beyond sitting at a computer. That included opportunities to make connections with her and their classmates.

She was inspired to use her students’ pets as a future teaching tool after an end-of-class chat where they enthusiastically shared photos of their dogs.

Tichon picked up on their engagement by using their dogs’ names to teach a class on setting up a basic randomized experiment. The pooches had to run a timed obstacle course with three possible starting points. Students analyzed the data using computers to see if one led to faster times. The bonus was the surprise of seeing their pets’ names on the assignment.

Like Guderian, Tichon incorporates rituals and routines. She sends a Sunday evening reminder email detailing the classes, labs and what’s due in the coming week to help keep students on track. She includes an encouraging message.

“There’s something important about actually telling someone I care,” says Tichon.

“There’s something important about actually telling someone I care.”

For her third-year classes, Tichon continued her regular classroom practice of a lesson-based prompt question at the end of the day.

“I always told them if you want to say anything else, or talk to me, or tell me anything, include it in there and then we’ll start the next class by talking about it.” The students responded. They had fun with it, too. Some included a stats joke, she says, others added photos.

“I had 325 students that I was having this back and forth with and they each got at least one and usually two or three times a week, a chance to say something personally to me,” says Tichon.

There have also been teaching benefits from remote learning. Guderian says he’s going to continue with pre-recorded lectures when students return to campus, allowing his in-person class time to focus on giving the students experience with the concepts they will have watched already. The pre-recorded lectures are an artifact he can keep and students can return to them as an adjunct to note taking.

“I think we’ll definitely look back and recognize that there were some things that we’ve learned from this experience that we can take forward,” Webb says. “I think we’ve definitely learned how to work with technology far more effectively.”

TeachingLIFE

UM is where teaching, learning and research collide to create an outstanding educational experience. TeachingLIFE tells the stories of our innovative educators and their impact on student success.

Learn more about TeachingLIFEOther TeachingLIFE articles

About CATL

The Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning is an academic support unit that provides leadership and expertise in furthering the mission of teaching and learning at the University of Manitoba.

Learn more about CATL