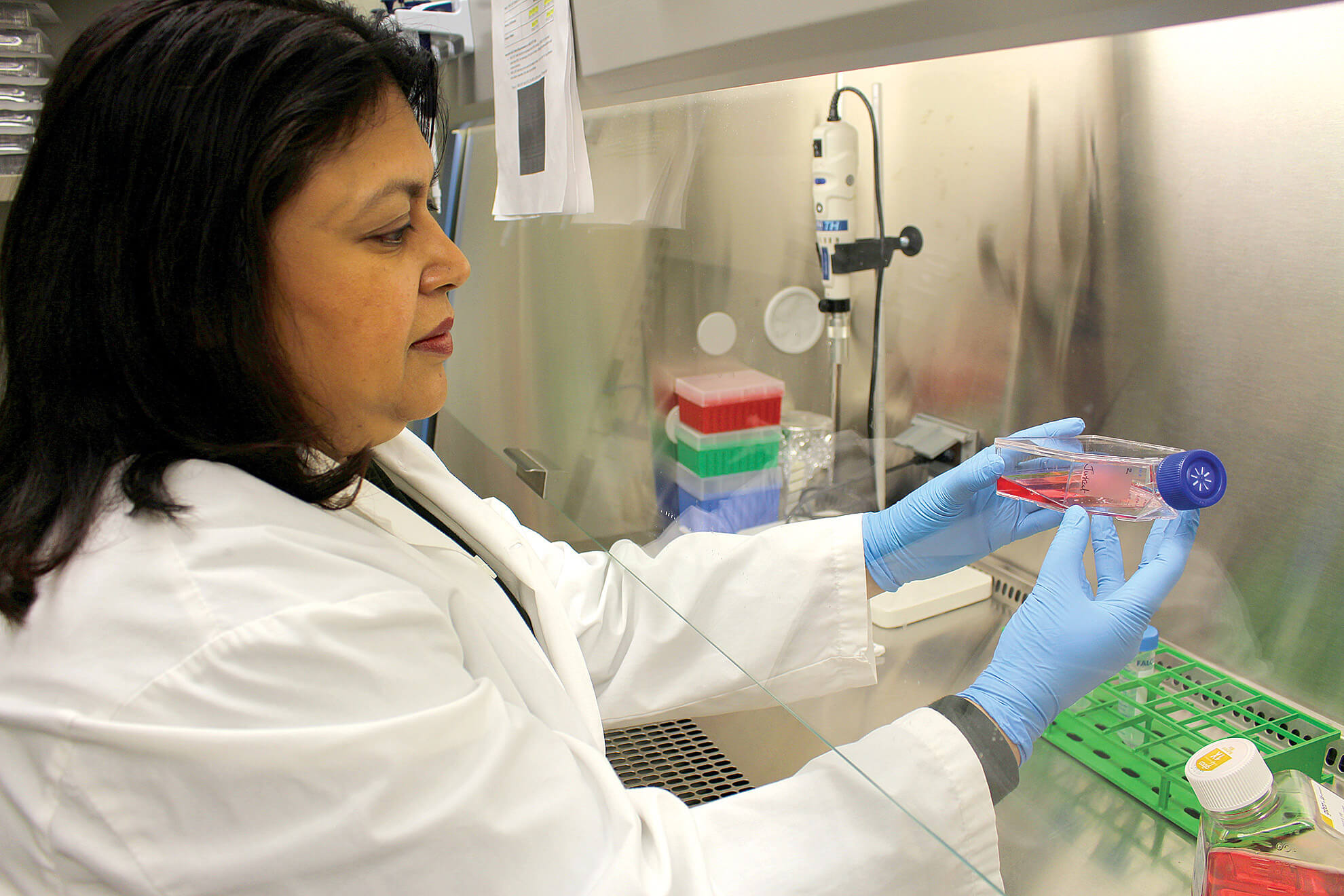

Professor Neeloffer Mookherjee, CIHR Sex and Gender Science Chair in Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Max Rady College of Medicine.

Experimental equity

Women with asthma tend to experience more severe symptoms than men. Women are also more likely to be non-responders to steroid treatments for the disease. “That means women are more likely to develop uncontrolled asthma,” says Neeloffer Mookherjee, a UM immunologist whose research focuses on lung inflammation. “Yet these sex-related differences have largely been ignored in drug development research, which has taken a one-size-fits-all approach. If drug-testing experiments are skewed toward males, the treatment can be less effective when applied to females.”

The professor of internal medicine and immunology in the Max Rady College of Medicine says scientists are only beginning to investigate how disease risk, disease progression and response to treatment differ between the sexes in many illnesses.

Professor Neeloffer Mookherjee.

Mookherjee’s expertise in this emerging approach to research has earned her a prestigious, four-year funded position as Canada’s first Sex and Gender Science Chair in Circulatory and Respiratory Health. The chair was awarded in 2020 by the Institute of Gender and Health, part of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“The entire field of incorporating sex and gender-based analysis into biomedical and health research is very new,” she says. “Canada is becoming a world leader in this field, and this chair will allow my lab to be at the forefront of advancing it. The ultimate goal is personalized medicine that tailors treatment to individual characteristics, including biological sex.”

“The ultimate goal is personalized medicine that tailors treatment to individual characteristics, including biological sex.”

Mookherjee, a UM faculty member since 2008, studies the molecular processes involved in chronic inflammation. In her lab at UM’s Manitoba Centre for Proteomics and Systems Biology, she conducts some of her experiments using mice, and others using human lung cells.

It has long been standard practice, she says, for immunologists to study mice or human cells of only one sex.

“Recently, data has started coming out that the immune response is wired differently in males and females,” she says.“That has been the impetus to take sex differences into account in designing our experiments and analyzing data. The knowledge and the tools to do so have only been available to researchers for about a decade.”

Mookherjee points to a landmark study co-led by scientists from McGill University and Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. Published in 2015, it showed that the long-accepted theory that pain perception relies solely on immune cells called microglia is only true in males. Interfering with the function of microglia blocked the sensation of pain in male mice, but had limited effect in female mice.

“This study revealed that in females, a different kind of immune cells—T cells—are also involved in perceiving pain,” says Mookherjee. “That was a paradigm-shifting result.”

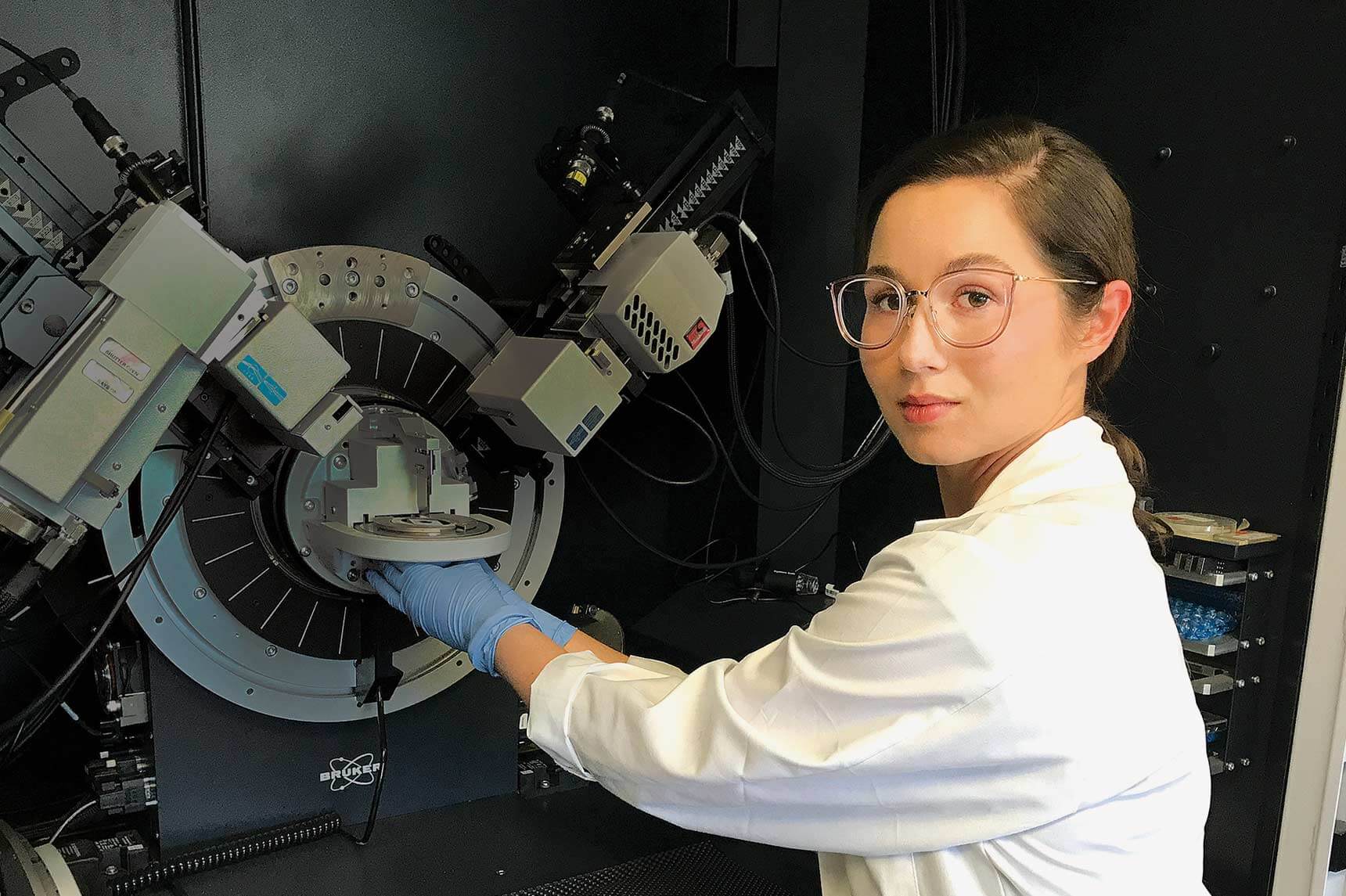

Image of peptides generated from Mookherjee's research.

Such findings have helped turn the tide toward equitable research design. “The major funding agencies are now requiring researchers to examine sex as a variable by using animal models and cell lines of both sexes,” Mookherjee says.

In asthma research, a key challenge is that both chronic lung inflammation and the steroid drugs that control it can weaken the immune system. That makes asthma patients susceptible to infections, including respiratory viruses.

Mookherjee’s current research focuses on innate defence regulator (IDR) peptides, which are synthetic versions of human “defender” molecules. In 2018, her team was the first to publish evidence that IDR peptides are effective against asthma. “These peptides can control both inflammation and infection,” she says.

Her lab is now investigating sex-related differences in IDR peptides’ effects on the immune system. “We’re starting to identify inflammatory proteins in the lungs that differ in male and female mice when they’re exposed to asthma-inducing allergens. In a year or so, if we detect the same differences in lung cells from asthmatic men and women, that will be exciting.”

Mookherjee in the lab.

Mookherjee also studies the inflammatory process in arthritis—another disease that is more prevalent and severe in women. In preparation for including sex as a variable in her arthritis research, she plans to develop female mouse models with various kinds of arthritic joints.

A unique aspect of Mookherjee’s Sex and Gender Science Chair is that it includes dedicated funding for outreach, communication and capacity-building. That is enabling her to promote sex and gender-based analysis through events such as workshops and symposia.

She also belongs to a number of networks and groups, such as the Biology of Breathing Group at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba. “Through these affiliations, I’ll be able to advocate for sex and gender-based analysis and train researchers to integrate it into their own research programs,” she says.

“The major funding agencies are now requiring researchers to examine sex as a variable by using animal models and cell lines of both sexes,”

“We’re starting to identify inflammatory proteins in the lungs that differ in male and female mice when they’re exposed to asthma-inducing allergens. In a year or so, if we detect the same differences in lung cells from asthmatic men and women, that will be exciting.”

ResearchLIFE

ResearchLIFE highlights the quest for knowledge that artists, engineers, scholars, scientists and students at UM explore every day.

Learn more about ResearchLIFE