Taking up the work of Reconciliation

How a new measuring tool based on research can push us further down the path to good and just relations

The mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was to inform all Canadians about what happened in residential schools. The TRC documented the truth of Survivors, their families, communities and anyone personally affected by the residential school experience. This included First Nations, Inuit and Métis former residential school students, their families, communities, the churches, former school employees, government officials and other Canadians. The TRC also hosted national events in different regions across Canada to promote awareness and public education about the residential school system and its impacts.

Funding for the TRC began in 2007, and it took several years to define its mandate. Its work concluded in 2015 when it transferred all of its records to the safekeeping of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), created in fulfillment of part of the TRC mandate as a permanent resource for all Canadians.

Ry Moran, associate university librarian – reconciliation, University of Victoria. Photo: Nardella Photography

When Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its 94 calls to action in 2012, it was a big question for all of Canada: of how—and even if—this work would be taken up. It would take years to achieve. And how would we know when we’d arrive at Reconciliation?

But as many Indigenous leaders and educators point out, because it’s relational in nature, Reconciliation is less of a question of “arrival,” and more a matter of working for continual, incremental progress in building understanding and relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.

“We have a number of goals, one of which is to understand what Reconciliation means to Indigenous and non-Indigenous in Canada.”

And now, with the inauguration of the Canadian Reconciliation Barometer project, the digital tools that have become common over the past decade will help to assess the progress being made.

“We have a number of goals, one of which is to understand what Reconciliation means to Indigenous and non-Indigenous in Canada,” says the project’s principal investigator, Katherine Starzyk. As an associate professor of psychology at the University of Manitoba, Starzyk focuses on psychometrics in her academic work—relying on theory and consultation to know what questions to ask and then large surveys as well as advanced statistical methods to develop statements or questions that are valid and reliable.

Monument located at Long Plain First Nation, to those killed in the 1942 airplane crash that killed students returning home from residential school.

How to measure progress?

Ry Moran calls the Barometer “a complementary tool” to the work being done by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), which was created in fulfillment of part of the TRC mandate as a permanent resource for all Canadians. Moran worked as the first director of the NCTR, established in 2015.

Simply put, the Barometer will provide more data for how we are doing as a nation, he says. “Whether we are taking substantial steps in improving the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, [and] whether or not the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples are being protected and promoted.”

Starzyk notes that the project currently has 13 indicators of Reconciliation, which may evolve as the project continues.

To pinpoint factors that could be used to measure progress over time, the project drew on input from Survivors, Elders and Reconciliation leaders, and research through NCTR, including Survivor statements and transcripts.

“We wanted to listen to people rather than just come up with an idea ourselves,” she explains.

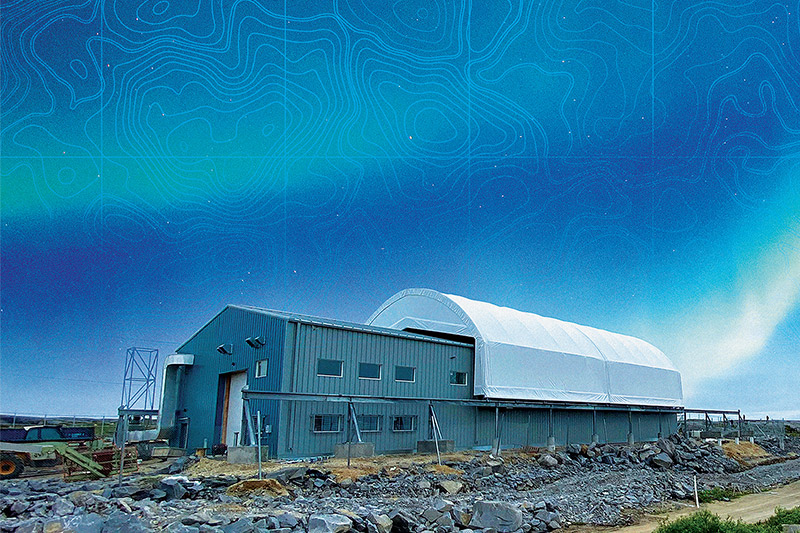

MacRae Library at Long Plain First Nation

The research is being led by a team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, and the project has also partnered with Probe Research to increase its polling capacity.

Highlighting the gaps in understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada and comparing progress across sectors of society, the Barometer’s current indicators include: Good understanding of the past and present, Acknowledgement of ongoing harm, Respectful relationships, Personal equality and Systemic equality.

Defining Reconciliation Forward

Any attention to its progress equally brings into view the multifaceted aspect of Reconciliation and what it means—how it’s understood by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, notes Brenda Gunn, current academic and research director at the NCTR. Gunn, who is also a professor at UM’s Faculty of Law, joined the project in 2021 after starting her NCTR position.

Gunn says that a great value of the Barometer is how it “provides a perspective on Reconciliation, and a definition and a place to work from.”

“There are lots of definitions out there, but part of what we have here [with the Canadian Reconciliation Barometer project] is a definition and an approach and indicators of Reconciliation that are grounded in the years of research that are drawing on existing research [through NCTR]. But the other starting point is that residential schools are just one part of a broader colonial project that was grounded in law and policy for the assimilation of Indigenous peoples.”

“The hope is for the findings to help inform future public policy,” Gunn adds.

“So if we accept that Reconciliation is complicated and that residential schools were part of a coordinated approach to [Indigenous] assimilation grounded in law and policy, then I hope that it becomes clear that part of what we need to do in achieving Reconciliation, moving forward, is to … address the laws and policies that supported residential schools, and its legacy as it exists today—because we know the impacts are ongoing.”

Monument at Millbrook, near Truro, Nova Scotia paying tribute to Glooscap—a legendary figure to the Mi’kmaq people of Nova Scotia.

The Long Walk Toward Reconciliation

For, as Moran asserts, “The harm inflicted upon Indigenous peoples is not only a problem for Indigenous peoples. It is a Canadian problem that requires all Canadians to take responsibility and action to repair the damage done.”

“The harm inflicted upon Indigenous peoples is not only a problem for Indigenous peoples. It is a Canadian problem that requires all Canadians to take responsibility and action to repair the damage done.”

The Barometer is intended to help prevent regression and ensure continued commitment to and investment in Reconciliation, as he puts it.

“The idea of a just, fair and equitable society—and Canada —still has to be created, and the continuous nature of it is something emphasized by the calls to action.”

Starzyk agrees. “The walk toward Reconciliation will be a long one and lead us down many paths.”

Read more about the Canadian Reconciliation Barometer project and its first report, released in February 2022

Watch the Café Scientifique discussion on “The Canadian Reconciliation Barometer” (Jan 11, 2022)

ResearchLIFE

ResearchLIFE highlights the quest for knowledge that artists, engineers, scholars, scientists and students at UM explore every day.

Learn more about ResearchLIFE