The not so sweet truth about food politics

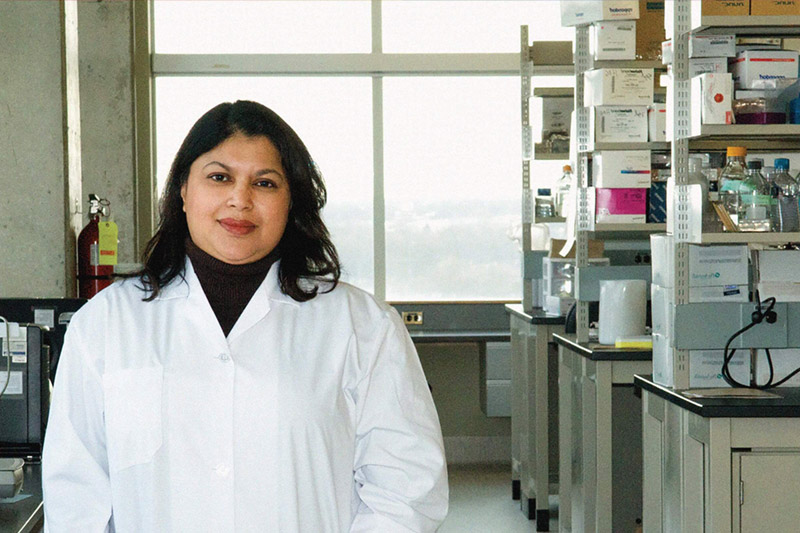

Identifying inequities in Canadian food policies is what Natalie Riediger undertakes. Research by this assistant professor in UM’s Department of Human Nutritional Sciences demonstrates how the distance between governments and the legislation they propose detrimentally affects marginalized communities, particularly First Nations in both urban and rural centres, such as those living on reserves and in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

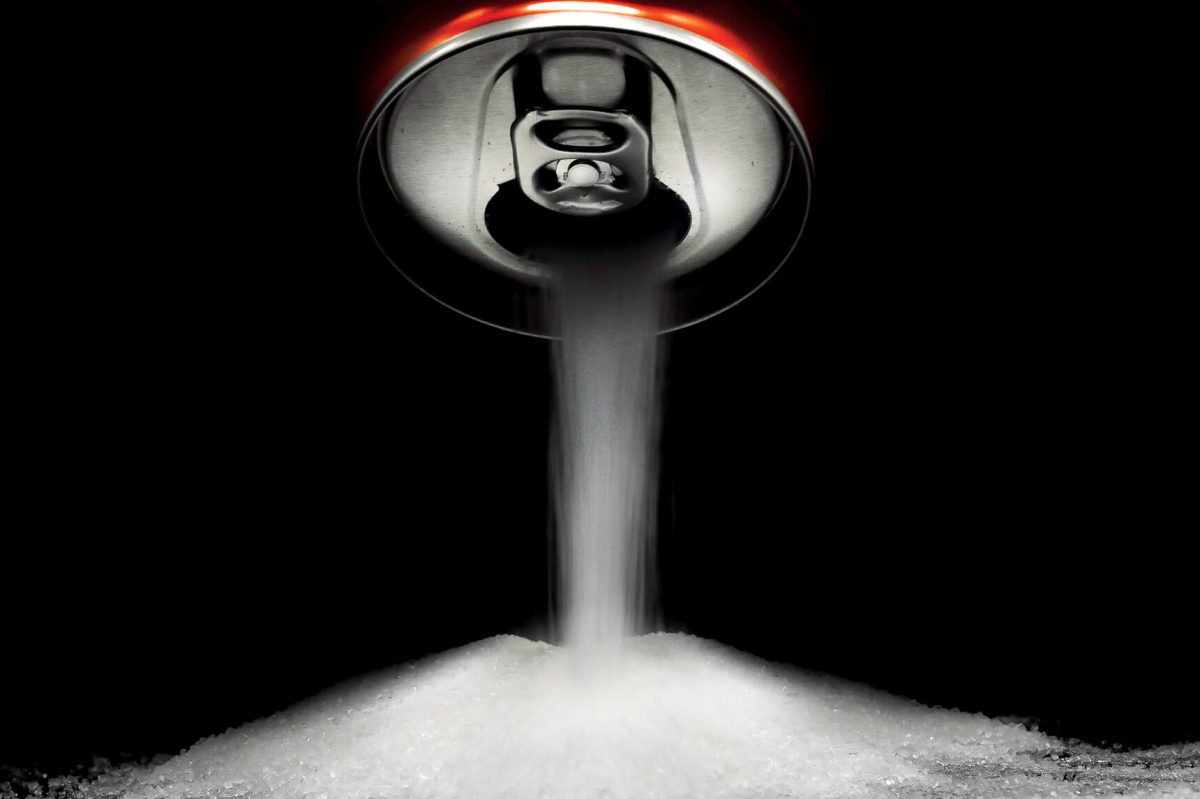

Because Riediger’s research examines the legal contexts surrounding a proposed tax on sugary drinks, she partnered with Myra Tait—an alumna of UM—now an assistant professor at the University of Athabasca and First Nations lawyer to understand the legalities behind its enactment. They question whether governments can legally enforce the tax, as under the Indian Act, they cannot tax on reserves. However, as Riediger mentioned in our interview, “the Indian Act plays a big role in taxation on reserves, but it is its own conversation.” Self-determination must be at the forefront of any discussion.

“The Indian Act plays a big role in taxation on reserves, but it is its own conversation. Self-determination must be at the forefront of any discussion.”

Instead, Riediger is focusing her attention on understanding the social, economic, and cultural contexts that may influence the acceptability and effectiveness of a proposed tax on sugary drinks, which the Government of Canada considered in 2016, though did not implement.

Although the World Health Organization and Diabetes Canada supported taxing sugar-sweetened beverages in hopes to influence healthier choices, as Riediger’s research explores, this policy may be harmful to marginalized communities. In working with Indigenous Peoples, she uses food inequities research to reveal the complicated nature of this proposal.

Natalie Riediger, assistant professor in UM’s Department of Human Nutritional Sciences.

As it turns out, it is much more complicated than simply making a healthier choice at the supermarket. Riediger says that initial inquiries that led to her current project with the National Indigenous Diabetes Association indicate the legal contexts that would follow its implementation are nuanced and complex, “something governments should consider if implementing this tax.”

The target population for her research includes Indigenous residents in urban and rural settings: Winnipeg, Manitoba focusing on the North End, a central urban hub for Indigenous Peoples, and Flin Flon, a border town between Northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. As well, she includes residents in First Nations reserves across Manitoba.

Winnipeg, home to one of the largest populations of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, exposes the contexts of Riediger’s research. Before COVID-19 lockdowns, she and her team interviewed Indigenous adults in the urban and rural settings to obtain their perspectives and attitudes on taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. To ensure comparative data, she interviewed residents in River Heights, a predominately middle-class neighbourhood in Winnipeg.

“We uncovered various nuances in which inequities could emerge,” says Riediger. “For instance, small business owners vocalized their concerns about the impacts of the tax due to provincial cross-border shopping. And, ultimately, we found that [soda] pop is very classed and folks who consume it are susceptible to judgement.”

Many participants from River Heights supported the tax, as they did not perceive it as negatively affecting them. One participant expressed that “pop isn’t even a food, so why shouldn’t it be taxed?”

Indigenous residents in the North End and Flin Flon were much more skeptical of its positive impacts and had substantial concerns regarding negative impacts among people who are food-insecure or lack access to clean drinking water. Residents became more trusting of the tax after they were asked what they would want the revenue to go towards.

“They were more comfortable with the idea when they felt they had a say in the matter,” indicated Riediger. “Once they knew how the tax would promote health in their communities.”

Thus, the inequities surrounding the sugar-sweetened beverages tax expose colonial narratives; to combat these inequities, community input, self-determination and trust are critical. Riediger and her team argue that any government, federal or provincial, should consider this context before implementing this potentially devastating tax.

Many research participants only realized the overarching complexities of the tax when they recognized familiar beverages, such as Frappuccino’s, sweetened coffee, diet drinks and juices, whose eligibility for taxation may be fraught. Riediger suggests that it is almost like prompting interview participants to ask, “Is my sugar okay?”

Her team is identifying intersecting issues within the research as they examine how, along with pop as a classed beverage, the actions of carrying it around in a shopping cart or purchasing it and giving it to a child can be stigmatized for Indigenous Peoples. There are multiple oppressions taking place simultaneously, which can be particularly detrimental for Indigenous mothers, who may experience judgment for giving pop or sugary drinks to their child, for their weight and their poverty. “Health is much more than pop and what we eat,” says Riediger.

Food security research tells us that the inability to purchase food increases stress, injuries and affects mental health. Riediger’s findings indicate that many Indigenous Peoples are not convinced that they will consume less pop if a tax is implemented, as pop is part of community gathering and socializing—although she says that “this ‘norm’ is changing.”

Food security research tells us that the inability to purchase food increases stress, injuries and affects mental health.

“This research is part of a global conversation that requires critical perspectives to ensure the inclusion of Indigenous voices during policy discussions,” shares Riediger. For her, conducting interviews and hearing the voices of Indigenous Peoples is fundamental to the research, as this project identifies the gaps in overarching policy initiatives.

She recognizes the power of listening to experiential knowledge and those directly impacted by the tax. “We need to give people time to pause, listen and really consider, or reconsider the tax,” comments Riediger.

“As a mixed-methods researcher, I recognize the importance of numbers, [but also] the social meanings of the community.”

The Nuances

Riediger’s research is essential as it identifies the complexities of taxing sugary drinks in colonial contexts.

“Capitalism can be traced back to sugar production, and intertwined with capitalism, is colonialism,” she says.

An example would be the use of stolen lands to produce corn for corn syrup. The Indian Act may further complicate the tax when discussing its implementation in Indigenous communities. Although, it remains clear that paternalistic attitudes are still controlling the discourse surrounding legislation that will affect marginalized populations.

When interviewed, small business owners vocalized their concerns about the impacts of the tax due to provincial cross-border shopping and on lower income and working class Manitobans.

Many participants from River Heights supported the tax, as they did not perceive it as negatively affecting them.

Residents from River Heights were generally not of the opinion that the proposed tax will hurt many people, though there were concerns regarding potential lack of fairness.

ResearchLIFE

ResearchLIFE highlights the quest for knowledge that artists, engineers, scholars, scientists and students at UM explore every day.

Learn more about ResearchLIFE