It's insufferable gobbledygook. What did you expect?

Rare birds: The good, the bad, the turkey

Early American poet Emily Dickinson once suggested that good poetry gets under the skin and into the bones — and maybe blows off the top of your skull!

“If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry, ” she wrote. ” If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?”

There are a million more stinkers for every great poem (a compendium of rare birds follows). But how does someone identify that exotic species, the turkey?

In light of tonight’s Bad Poetry Night at The Hub, organized by student life, UM Today asked the university’s poet and assistant prof in the department of English, film and theatre, Alison Calder, how she knows when a poem is bad — as bad as it can be.

ALISON CALDER: Anyone can write a bad poem, but is your poem bad enough? This handy checklist will remind you of just how bad your poem can be!

1) Did you write it an hour ago?

2) Does the explanation of the poem need to be longer than the poem itself?

3) Do you need to provide your audience with decoder rings so that they can unlock your cryptic genius?

4) Is the poem missing at least two of the following elements: nouns, verbs, or adjectives?

5) Is it about how you used to love someone, and then they didn’t love you anymore, so you murdered them, and the last line is the drip, drip, drip, of their blood hitting the floor?

6) Does it rhyme?

7) Does it contain the phrase “I am alone,” which you’ve emphasized by stringing it down the page like you are channeling ee cummings, whom you’ve never read because you are afraid of “being influenced”?

8) Was it easy to write?

Alison Calder teaches Canadian literature and creative writing in the department of English, film, and theatre, Faculty of Arts. Her second poetry collection, In the Tiger Park, will be published in April 2014.

*******

Rare birds by great poets: Poems

Emily Dickinson: Hope is the thing with feathers

Most of the work of prolific and reclusive American poet Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886), aka the Belle of Amherst, wasn’t published until after her death. That was when her remaining family discovered over 1,800 poems, in 40 bound notebooks. Her wit, pathos and distinctive style have made her one of the greatest poets of all time.

Hope is the thing with feathers

“Hope” is the thing with feathers —

That perches in the soul —

And sings the tune without the words —

And never stops — at all —

And sweetest — in the Gale — is heard —

And sore must be the storm —

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm —

I’ve heard it in the chillest land —

And on the strangest Sea —

Yet — never — in Extremity,

It asked a crumb — of me

Wilco’s lead singer Jeff Tweedy was inspired by the poetry of Emily Dickinson for the single “Born Alone” from the 2011 album The Whole Love.

Don McKay: Sometimes a Voice

Birds figure prominently in the poetry of award-winning Canadian Don McKay. An avid birdwatcher and nature lover, McKay often employs themes of birding and flight, perhaps most directly in his 1983 work Birding, or Desire. Here’s an excerpt of his poem “Sometimes a Voice” from his book Another Gravity, which won the Griffin poetry prize in 2001.

Sometimes a Voice

Sometimes a voice — have you heard this? —

wants not to be voice any longer, wants something

whispering between the words, some

rumour of its former life. Sometimes, even

in the midst of making sense or conversation, it will

hearken back to breath, or even farther,

to the wind, and recognize itself

as troubled air, a flight path still

looking for its bird.

Karen Solie: Migration

Canadian Karen Solie’s third collection, Pigeon, also won a Griffin Prize, this one in 2010. Here’s her poem, “Migration,” from that book.

Canadian Karen Solie’s third collection, Pigeon, also won a Griffin Prize, this one in 2010. Here’s her poem, “Migration,” from that book.

Migration

– for Cathy

Snow is falling, snagging its points on frayed

surfaces. There’s lightning

over Lake Ontario, Erie. In the great central

cities, debt accumulates along baseboards

like hair. Many things were good

while they lasted. Long dance halls

of neighbourhoods under the trees,

the qualified fellow-feeling no less genuine

for it. West are silent frozen fields and wheels

of wind. In the north, frost is measured

in vertical feet, and you sleep sitting because it hurts

less. It’s not winter for long. In April

shall the tax collector flower forth, and language

upend its papers looking for an entry adequate

to the sliced smell of budding

poplars. The sausage man will contrive

once more to block the sidewalk with his truck,

and though it’s illegal to idle one’s engine

for more than three minutes, every one of us will idle

like hell. After all that’s happened. We’re all

that’s left. In fall, the Arctic tern will fly

12,500 miles to Antarctica as it did every year

you were alive. It navigates by the sun and stars.

It tracks the earth’s magnetic fields

Sensitively as a compass needle and lives

on what it finds. I don’t understand it either.

From Pigeon, by Karen Solie

Copyright © 2009 Karen Solie

Tim Lilburn: There Is No Presence

Equal parts philosopher, eco-activist, nature poet and Prairie mystic, poet and essayist Tim Lilburn is another Canadian award winner. His book Kill-site won the 2003 Governor General’s Award. A few years later, the book of selected poems, Desire Never Leaves: The Poetry of Tim Lilburn (edited by Alison Calder), included the poem, “There Is No Presence.” Below is an excerpt.

There Is No Presence

(excerpt)

There are geese over the water, flickering in bad light, something pushing

through

from the other side; here is desire,

a light around the tongue, world next

to a world, a garden that would appear if the word were found.

What glitters in things is a mountain, it can’t be held in the

mouth.

The heavy grasses; night bends from the waist and

goes down into them.

The last light is the intelligence, the smallness

of birds in wild berries.

The stars clank up, black-wet weight running

on the oil of anticipation.

The geese participate in the boiling dark and they

are a speech of it.

Gertrude Stein: Chicken

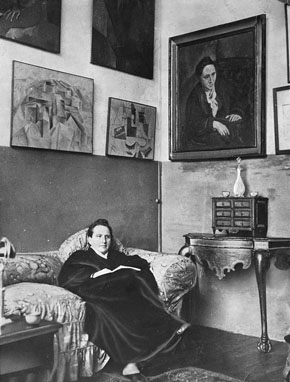

Gertrude Stein at her Paris apartment. Picasso’s cubist portrait of her hangs on the wall to the right.

American Modernist Gertrude Stein (1874 – 1946) took a decidedly avant-garde approach to poetry (along with narrative and drama), preferring to push the limits by decentring meaning and subject, rejecting realist linear narrative and logic and foregrounding “essences” through sound, rhythm and repetition. Her writing was heavily informed by the Modernist visual art movement of cubism (and vice versa). Tender Buttons, one of her most famous books, is comprised of prose poems and divided into three parts: “Objects,” “Food” and “Rooms.” “Act so that there is no use in a center” begins the “Rooms” section. Here’s Stein’s humorous take on the bird from “Food.”

CHICKEN.

Pheasant and chicken, chicken is a peculiar third.

CHICKEN.

Alas a dirty word, alas a dirty third alas a dirty third, alas a dirty bird.

CHICKEN.

Alas a doubt in case of more go to say what it is cress. What is it. Mean. Why. Potato. Loaves.

CHICKEN.

Stick stick call then, stick stick sticking, sticking with a chicken. Sticking in a extra succession, sticking in.

Wallace Stevens: Thirteen Ways

And finally, there’s this famous poem about rare ways of looking at a common bird by another American Modernist, poet Wallace Stevens (1879 – 1955).

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

I

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

II

I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

III

The blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.

It was a small part of the pantomime.

IV

A man and a woman

Are one.

A man and a woman and a blackbird

Are one.

V

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

VI

Icicles filled the long window

With barbaric glass.

The shadow of the blackbird

Crossed it, to and fro.

The mood

Traced in the shadow

An indecipherable cause.

VII

O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?

VIII

I know noble accents

And lucid, inescapable rhythms;

But I know, too,

That the blackbird is involved

In what I know.

IX

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

It marked the edge

Of one of many circles.

X

At the sight of blackbirds

Flying in a green light,

Even the bawds of euphony

Would cry out sharply.

XI

He rode over Connecticut

In a glass coach.

Once, a fear pierced him,

In that he mistook

The shadow of his equipage

For blackbirds.

XII

The river is moving.

The blackbird must be flying.

XIII

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.