New book fills gap in research on perpetrators of genocide

Master of Human Rights program director co-edits guide

Until within the last few years, very little research had been done on perpetrators of genocide, and so far, there has certainly not been any books published on how to do such research. Perpetrators were caught, brought to trial and locked away, but no one looked too closely at why they did what they did or circumstances contributing to their emergence – until recently.

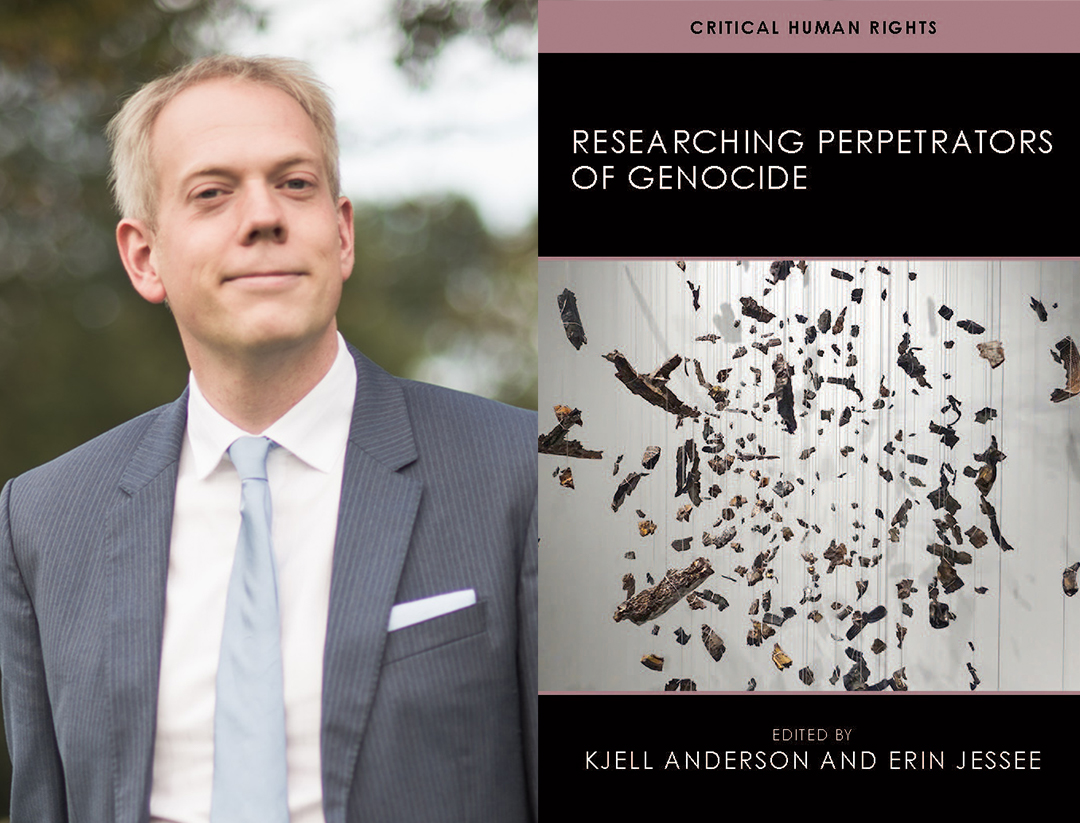

Talking to perpetrators involved many ethical and methodological challenges, not to mention the physical and mental hazards posed to researchers venturing into this field, their assistants and victims being interviewed. As two such ‘pioneers’ in this field, Dr. Kjell Anderson, director of the University of Manitoba’s Master of Human Rights (MHR) program and his co-editor, Dr. Erin Jessee, a senior lecturer in History at the University of Glasgow’s School of Humanities have pooled their experiences along with a number of other colleagues in a new book intended to guide others in this emerging area.

Researching Perpetrators of Genocide, officially launching March 11, 2021 from the University of Wisconsin Press, addresses challenges including overcoming biases, recruiting interview subjects, risk mitigation, self-care in precarious research environments and when conducting interviews relating to extreme violence, and ensuring the safety of interviewees. The book, a collection of case studies by multi-disciplinary scholars, describes a code of best practice for future researchers to follow while furthering studies in genocide, transitional justice and related areas. The book is intended to help guide researchers of perpetrators, and scholars of genocide in the ethics and methods of perpetrator research.

Anderson, who teaches human rights law at the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Law to both law and MHR students, shared his thoughts on how the new book contributes to furthering research in genocide and international criminal justice. (This interview was edited for length and clarity.)

Law: What was the impetus for publishing this book?

Dr. Kjell Anderson: I’ve spent years interviewing perpetrators and also victims of genocide and other mass atrocities, in a number of countries in Rwanda, Burundi, Bosnia, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Iraq…. I’ve probably interviewed at least 200 perpetrators. My colleague who co-edited the book with me, Erin Jessee, who’s an anthropologist and historian, similarly, she’s done interviews with perpetrators especially in Bosnia and Rwanda. For both of us, we realized that this topic was under-served.

Perpetrator research as a topic has certainly come along a lot in the last 15 years. Before that, almost nobody was doing it. Around the time of my PhD in 2007, there were very few people doing research on perpetrators. Now there are more, but it’s still a niche within a niche within a niche. This is the first book as far as I’m aware, which is about the methods and the ethics and all these issues that are involved in doing research on perpetrators.

It served an un-served need in the field: we realized how complex this research can be in the kind of dilemmas that we would encounter, a lot of which might have been unanticipated, just because we hadn’t done this kind of research before. Nobody had taught us how to do it until we actually started doing it years ago.

Law: Is there anything here that the Juris Doctor and Master of Human Rights program students you teach at the University of Manitoba could take away from this book?

Anderson: I think so. Especially in terms of how to do research, I guess it’s two-fold. One area is just how to do research. I think law students, and maybe even legal scholars don’t often do interview-based research. More commonly, they’re looking at things like case law, sometimes they might do things like trial observation, or things that are maybe slightly ethnographic, but not so many people are doing interview-based research. Certainly, that’s something I could speak to, and inform the students and also more broadly, see the ethical implications of working on what you could call fraught political subjects, things that are very controversial, which applies to many contexts: it applies to Canada, and it applies to research ethics as well.

How do you deal with subjects who might be stigmatized, for example, who might even be condemned? How do you deal with governments that might be trying to stop you from doing your research? Or they might be trying to distort your research? How do you protect the people who are involved in that research?

Protection is different, obviously, in Canada than it is in a kind of society experiencing violent conflict. But at the same time, we have these issues in Canada as well, we think about vulnerable subjects. So that’s definitely one thing I think that I can teach them. And if they’re studying genocide more broadly, then there’s probably much in the book that might be useful as well. For international crimes, but also crimes against humanity, war crimes.

Law: Why must this work be done? It’s such a frightening, scary topic. Will it benefit the furtherance of human rights and can it help in bringing perpetrators to justice?

Anderson: There are several things that it’s about. The research ethics, to me, also relate directly to human rights. If you’re doing unethical research, you’re probably also violating the human rights of your subjects in one way or another. It’s something I teach my students, certainly in the Master of Human Rights program, that when we’re doing human rights research, we also have to have the human rights-based approach to doing research. It doesn’t make sense to do research on human rights issues that exposes people to risk or that exposes them to other kinds of stigma or vulnerability or even physical threats in some case, or that we coerce people. Of course, we can’t do any of these things as researchers, if we want to respect the human rights of our subjects.

It also forms part of this broader literature on understanding genocide and understanding mass atrocities. You would hope that by understanding these atrocities, we can work to prevent them. That’s a complicated endeavor, very much embedded in politics, but important nonetheless. Even for people working on international criminal trials, I’m sure some of them might find the book also useful and interesting, because certainly they encounter a lot of the same dilemmas, obviously through a legalized context, but if you think of witness protection, there are a lot of actually similar and overlapping issues to what we would deal with in terms of vulnerable subjects, for example, and maybe also understanding the nature of perpetrators and perpetration as well.

Law: How do you overcome your biases? You’re sitting down with someone who has committed terrible crimes, and you’re bringing things to the table as an interviewer. How do you do that?

Anderson: I had a lot of assumptions about perpetrators before I started interviewing them. I would say my assumptions have changed. It’s almost cliché. Now, for those of us who study perpetrators to say this, and you can even go back to Hannah Arendt [political theorist] and her concept of the banality of evil, which is much used and maybe much criticized. But fundamentally, perpetrators are human beings, so you have to approach them as human beings. That was something that disrupted my assumptions.

When I started the work, I had the feeling that – I kind of chuckle at it now – like I was sort of confronting evil. It probably wasn’t that heightened, but I think there was a little bit of that in my approach to wanting to work on perpetrators.

In Rwanda, for example, most of the perpetrators I would interview – and I interviewed about 80 – were farmers who’d never committed crimes before they became involved in the genocide in 1994. They hadn’t committed any crimes since they became involved in the genocide. So that disrupts assumptions about deep-seated pathologies, whether they be found in ideology, or in character flaws, or in psychosis, or mental illness. You might find that with some perpetrators, but most perpetrators don’t fit those kinds of extreme stereotypes.

It’s not that I’ve reached a place where now I have no bias about anything. That’s not really the point. In a sense, it’s more about thinking critically about your place in things, and approaching people as human beings no matter who they are, and no matter what they’ve done, or no matter what they’re accused of doing. So that’s to me where overcoming bias comes in. But I wouldn’t say that I’m totally free from bias. I might feel more empathetic when I’m interviewing a victim, perhaps, who’s telling me about something that happened to them, than I would a perpetrator, or somebody who did something.

Approaching people with hostility in an interview is not a very effective method, either. Aside from the ethical issues, I think you’re just going to shut people down. It’s not that I’m a sycophant, and tell them what they want to hear. But at the same time, I maintain a pretty neutral demeanor, and that helps to bring things out of them. They feel more comfortable speaking with you and like they can tell their story, just like a victim would also want to do.

Law: Will this book offer some help to future lawyers pursuing a career in the area of international criminal law?

Anderson: I think it might, especially the investigative phase. A lot of the people doing interviews aren’t necessarily highly trained investigators. It sounds like a funny thing to say, but it’s actually true. In the case of the ICC [International Criminal Court], a lot of the people hired as investigators didn’t come with police backgrounds, unlike for other courts. A lot of them were lawyers, in fact, but they then had to train to be investigators, which to be honest, hasn’t always worked out perfectly smoothly. There’s much to be learned about the process of talking to people and I think it also relates to things like witness protection, bearing in mind that there are legal frameworks that they’re operating within, which are different than what I would be doing if I’m just interviewing somebody for my own research.

In the other thing I’m working on – a book on Dominic Ongwen, who was abducted as a 10-year-old child by the Lord’s Resistance Army rebel group in northern Uganda, led by Joseph Kony, his war crimes and crimes against humanity trial at the International Criminal Court just ended. This is a case where I think understanding more about the social processes underlying perpetration is important – you think about somebody being a young child, and how their perspectives were shaped just by being in this group, and how it actually contributed directly to their offending. If you’re a defence lawyer for a Dominic Ongwen or somebody like that, these are things you have to consider even as you get into defenses like duress, or mental illness, understanding the social and cultural context is crucial to actually mounting a legal defense in that case.

Law: Can you talk about the papers included in this book, including the chapters you and your co-editor wrote?

Anderson: Both Erin and I co-wrote two chapters and we each wrote one of our own. In terms of the contributors, it’s a very interdisciplinary group that we’ve assembled. We have people who are historians, anthropologists, lawyers, and the range of cases is similarly diverse. We tried to get cases from every continent. We didn’t quite succeed, but we came close. We have people working on Bosnia, we have papers on Rwanda, on Cambodia, on Syria, Argentina, and on Hungary.

The chapter that I solely authored is kind of conceptual. It’s called “The Perpetrator Imaginary,” about different perspectives on perpetrators. It starts with [Jean-Paul] Sartre’s analogy of the cube, that you could only see one side of the cube and that’s your whole perspective. I’m using this to describe perpetrators and differentiating between the perspectives that an artist might have on perpetrators versus a lawyer versus a victim versus the perpetrator themselves, versus the researcher. I’m arguing that our understanding of perpetrators is shaped by our own perspective and how we’re approaching perpetrators, what we’re actually trying to get out of them.

There are also legal chapters dealing with treating perpetrators as respondents. That’s the concept of the authors Damien Scalia, Marie-Sophie Devresse who are writing from a legal perspective. They’ve interviewed people at both the Rwanda tribunal and the Yugoslavia tribunal. They’re saying that these people are not only subjects of the judicial system, but that they’re also research subjects, that they’re also people who have something to say. They’re also sources of information beyond the context of the criminal trial. It’s a diverse group of people and a diverse group of papers.

At the end of the book, Erin and I wrote a chapter which is a tentative code of best practice for perpetrator research. We’re trying to make it also practical. People who are doing research with perpetrators can look at this thing and think about, what do I need to do as I’m conceptualizing my research?

What do I need to do to get a research permit? If I’m researching in another country? Even in your own country, you need to research permit. How do I actually locate perpetrators? How do I talk to perpetrators once I’m in an interview setting?

And of course, crucially, how do we protect people, both the people who are the research subjects, but also often overlooked: people like research assistants, translators, who maybe you leave the country, and they stay in the country if you’ve gone somewhere else to do research. You have to be really conscious of the effects that the publication of your materials might potentially have in some cases on these people as well.

Law: Do you have any thoughts on why so little research has been done in this area? Genocide has been happening for a long time. Have we all been too squeamish to take this bull by the horns and deal with it? What is different now as opposed to in the past?

Anderson: I’m not sure what’s different. But I think you’re right in the sense that people avoided not just perpetrators, maybe especially perpetrators, but they also avoided researching genocide. In terms of levels of squeamishness to use your phrase, genocide is one thing, and … people don’t want to hear that you’re trying to understand perpetrators. You’re not necessarily exonerating them morally, or otherwise or legally. But people are nervous about the idea of understanding something which I think it’s easier to just think these people are really bad people. Some of them are probably really bad people. I think I’ve probably met a few as well, but a lot of them aren’t. And I think that’s actually more troubling.

For people to grapple with that I wouldn’t go so far as to say it can happen anywhere at any time. There are certain social conditions present, obviously. But things change over time. I wouldn’t really rule it out – genocides happening. Many genocides have happened throughout history in many, many places. So, I think squeamishness is one thing.

I think there’s a kind of moralizing, which is troubled, especially by studying perpetrators. It’s also complicated research. If you’re doing archival research, that’s one thing. That could be difficult – I’m not taking away from that. But if you’re actually going to a country where atrocities are happening, or where atrocities did happen recently, then there are all kinds of risks and complications that are endemic to that, that are part of that process. It’s politically contested. Genocide, in almost every case, is quite controversial, making it more difficult to do research. You might put yourself in personal risk in certain circumstances.

You have to go through these complicated research ethics processes. We have been through many of them, and they’ve never been easy for me. I don’t think I’ve ever had a project where they just said, “Yeah, great, you’re done. Let’s move on.” Because I’m always dealing with abuse and violence and marginalization and political controversy, all wrapped up into one package.

So, I think that is the reason there’s been a bit of reticence to study it. I’m not sure why that’s changed. Maybe it’s just that some people started doing it. Before Erin and I, there were some people and it just sort of picked up some momentum. I still think it’s relatively small.

Law: Were there any submissions for the book that address the genocide of Indigenous peoples in the North American context and Residential Schools?

Anderson: Erin and I actually tried mightily to get a submission on Residential Schools. Some people came close, and sometimes it was just that they were busy. But actually, I think people were reticent to be in a book that had the word ‘perpetrator.’ This is something about the context of Canadian Residential Schools, because – I’m simplifying the complex and long history – but in the Residential School context, you had some people who were very obviously perpetrators, in terms of people who were doing physical abuse, for example, but then a lot of what happened in terms of the injustice, was about this very systemic process of dispossession, and of marginalization of Indigenous peoples that was rooted obviously in a very racist view of these peoples.

At the same time, a lot of the people who might have been involved in Residential Schools, it is difficult to put the label ‘perpetrator’ on them. Some you could probably do it. But let’s just make up an example: the teacher who might be teaching in a Residential School, maybe they’re not directly involved in physical abuse. But the whole system is abusive. Is that individual then a perpetrator? I’m not saying they’re not a perpetrator. But the answer is complicated.

That’s what some of the scholars that we spoke with shied away from a little bit, even though they’ve written about Residential Schools. Sometimes they use the label ‘genocide’. For example, some of them had done interviews with teachers, because there are some living teachers of Residential Schools that they were reluctant to label [as perpetrators]. It might also have something to do with the timeframes we’re talking about, because as we know, the Residential School system manifested in different ways in different time periods. If we look at it writ large, it was certainly an abusive system aimed at the elimination, essentially, of Indigenous identity in Canada.

Law: Any key things that you would want people to know about this book and your process of publishing it?

Anderson: I think it’s of interest to people who are certainly doing any kind of sensitive research involving human subjects. Interview-based research primarily is what we’re talking about. Whether or not they’re doing research on genocide, it’s still got relevance for other areas. Certainly, if you’re doing research on genocide, perpetrators, maybe it’s being immodest to say this, but I would have liked to have had a book like this, when I started doing the research years ago, and I didn’t have that much mentorship in terms of the methods side of things, because actually, my supervisors also hadn’t done this kind of research.

So, I did have to learn through books and through talking to people, and there were things I could have done better. Inevitably there is this kind of iterative learning process. If somebody is embarking on this research for the first time, this book can certainly help them but people who are more experienced researchers would probably find something useful in the book as well.

Further media about Researching Perpetrators of Genocide, Kjell Anderson and Erin Jessee, editors:

Podcast interview of Kjell Anderson and Erin Jessee. New Books in Genocide Studies with Jeff Bachman, senior lecturer in Human Rights at American University’s School of International Service in Washington, D.C.

Book Launch: Researching Perpetrators of Genocide. March 11, 2021 at 9:00 a.m. (CST). Perpetrator Studies Network. Join event at Zoom link here.