Making smarter devices

Technology of the future developed at the U of M

A big part of Dr. Pourang Irani’s job is to dream.

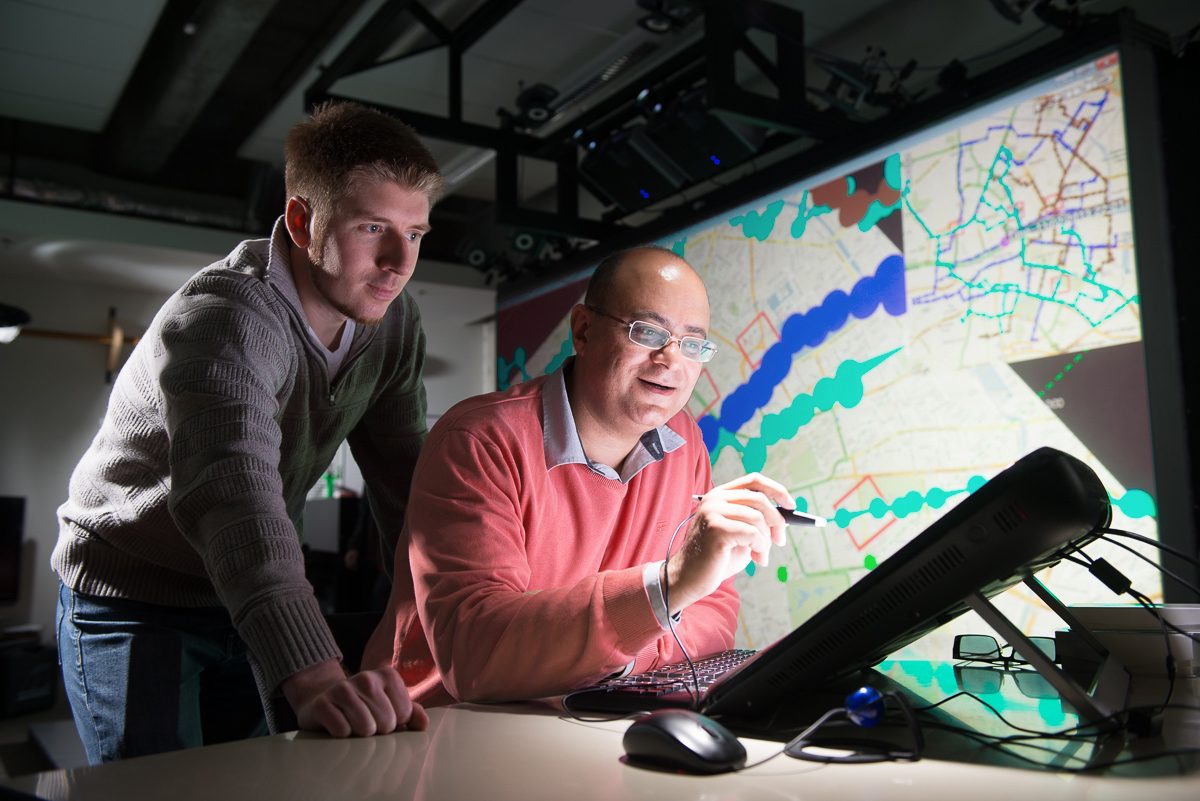

The computer scientist makes the technology often considered science fiction a reality, giving the world new ways to access the digital experience. Think Tony Stark in Iron Man and how the superhero interacts with projected screens and uses head-worn displays to make decisions on the fly. Irani’s role may sound complex—Canada Research Chair in Ubiquitous Analytics—but he insists his goal is simple: to help people navigate the daily storm of data coming our way.

“It could be holographic. It could be contact lenses you wear. It could be devices that are floating and flying through the air. It could be any number of these,” says Irani. “The question is, ‘How do we use data and make sense of it on a day-to-day basis, to improve our lives?’”

Smarter devices

The Faculty of Science professor and his students at the Human-Computer Interaction Lab bring to life the wearable technologies and hologram projection devices of tomorrow that could give new tools to disaster-response workers, doctors and educators.

The team enhances the use of smart phones, watches and tablets that allow “sense-making on the go, anywhere, anytime” believing that access to information shouldn’t be restricted to one physical space, but instead be available as people move around.

While smart devices already do this to some extent, Irani is looking at how to best display information so that it’s easier to interact with and make sense of. Mobile devices, for example, have limited screen space and people frequently put them down to work on a laptop or desktop for more data-intensive tasks.

“We’re making these devices we carry even more powerful,” says Irani, who was a graduate student when he first began exploring this emerging field. “[This area of research] drew my interest in terms of its beauty and utility and function and design.”

Direct impact

Advancing our knowledge of human-computer interaction has a direct benefit for individuals, which also inspires Irani.

His research can be applied to real-life scenarios where users need access to information when both hands are in use. Surgeons or mechanics, for example, could scan information they see through contact lenses or head-worn displays. They could see graphics and analytics without looking away from what they’re doing.

“If you imagine the content to be spread around the device, not only on the device screen, but projected around it as well,” he says.

Interest in his research from industry has been hard to keep up with. In the next decade, big changes are coming.

“Say 10 years from now, the ability to see data appear on your countertop beside your sink as you’re washing the dishes may not be so unusual, so bizarre, so fictional,” Irani says.

To get there, he and his students are looking at head-worn displays like Google Glass, using the devices alongside desktop screens and effectively expanding the workable area by three or four times. They’ve also been able to apply this to mobile devices, allowing users to expand and interact with a much larger working area than the physical screen itself.

“It was very interesting to see that platform emerge,” says Irani. “We’re doing a lot of work in that area and trying to see how we can make it a powerful device, much more powerful than it is today.”

But at the same time Irani says he treads carefully. He’s well aware that the technologies he’s trying to improve are also criticized for intruding into people’s personal lives and values. Some of his research found mobile devices can alienate people from one another, including in family settings. That’s not a new phenomenon.

“How do you balance that? I think five, 10 years from now I’m going to be interested in looking at how these personal technologies that can be so powerful in giving us what we need at any given time for any particular purpose and be so efficient, not distract us from the more important things in life such as person-to-person interaction. How we do it? I don’t know. For now I’m busy building the technologies but I like to think about how they help us live better together.”

Shaping the next generation

Irani shares his passion with the PhD students he supervises. He beams when he talks about students who have interned at Microsoft, are working at China-based Lenovo Research, and teaching and researching at the prestigious Dartmouth College.

“It’s not just fun [working] with the technology but fun when you see students have breakthroughs,” he says.

One recent breakthrough kept Irani awake with excitement. “We’re looking at one particular style of data and information presentation with a new device that will soon enter the market. We’ve been cracking on it for a couple of weeks then just last night I got a video from the students—they cracked it,” he recalls. “I didn’t sleep until 2:00 in the morning. I was just so excited about it. I re-reviewed the video five times.” Irani is happy to be the bridge to his students’ success.

“You do your thing; you have fun and the students go on and do things that are bigger and better.”

For more information visit the Visual and Automated Disease Analytics (VADA) site.

Dr. Irani’s research is funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Research Chairs program, MITACS, the Province of Manitoba, and corporate sponsors Honda, Boeing, and Microsoft

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.

Pourang is a great researcher and one of the nicest people I’ve met!

Great story. Cool guy