Honouring distinguished achievement

During Fall Convocation, honorary degrees for distinguished achievement will be awarded to:

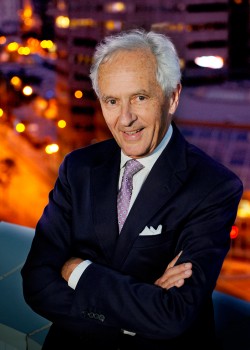

Michael F. B. Nesbitt

A businessman, philanthropist and patron of the arts, Mr. Michael Nesbitt grew up with an understanding that education opens doors. Eager to learn, he wasted no time and by 21 had completed two degrees at the University of Manitoba—in commerce and arts.

Following graduation, he headed to Toronto to work on Bay Street for the TD Bank and soon started a family, doing so on the advice of his dad who encouraged his son to: ‘Go explore, and come back only when you’ve got some life experience.’

When Mr. Nesbitt returned in 1965, he took the helm of his father’s mortgage company. He grew Montrose Mortgage Corporation into one of the largest privately owned mortgage banking and servicing companies in the country. Today, the firm manages $2 billion in loans from coast to coast.

As its Chairman and President, Mr. Nesbitt is known for leading by example. He believes if you’re ethical and hard-working that’s the type of employee you’ll attract, and hiring good people is key. It’s equally important to get out of their way and let them shine.

With five decades of experience, Mr. Nesbitt has been a beloved mentor to many, always mindful to teach in a manner that he’d want to be taught. When colleagues speak about him they use words like: integrity, inspiring and humble.

Few know the depth of Mr. Nesbitt’s philanthropic contributions in the home province he treasures. Out of the spotlight, he’s been building a better community by taking steps to: send more kids to Camp Stephens, attract more graduate students to Manitoba, and ensure Indigenous students have access to university. When Mr. Nesbitt sees a need, he finds a solution: in the mid-60s he helped found the first Montessori School in the province, and in 1977 he supported Winnipeg’s first public, co-ed squash courts.

Mr. Nesbitt has also shaped the creative landscape in Manitoba. Local organizations—including the Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, the Graffiti Gallery, the Manitoba Opera, and the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra—know well the impact of his generosity.

Mr. Nesbitt’s drive to make a difference has brought world-class exhibits to Winnipeg—the type of shows normally reserved for galleries in Paris or New York.

He is also eager to celebrate Winnipeg talent, commissioning artists’ work and underwriting project and exhibition costs. He has invested in people—like U of M alumnus Micah Lexier, a Winnipeg artist who in 2015 received a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.

Mr. Nesbitt also supported the Art Gallery of Ontario’s acquisition of a major installation of U of M alumna and Winnipegger Sarah Anne Johnson in 2009, ensuring the unique artworks stayed in Canada.

Believing in the intrinsic power of music, Mr. Nesbitt has been an enthusiastic supporter of the Desautels Faculty of Music. He helped establish the Babs Asper Professorship in Jazz Performance and later helped the faculty launch the Bridge Program to bring jazz music instruction to inner-city kids.

His steadfast support has made it possible for emerging artists and musicians to not only dream, but to dream big. One thoughtful gift at a time, Mr. Nesbitt has had a transformational impact on the projects and people he believes in.

Marie Wilson

Before she became a tireless advocate for Indigenous communities across this country, Dr. Marie Wilson was a 15-year-old who longed to explore.

She spent two weeks as an exchange student near Montreal and instantly her world was much larger than the small Ontario town where she grew up. She fell in love with the French language, and believed it was key to learning about different cultures.

By 23 she was on her way to Africa to teach high school students in the impoverished francophone country of what is now known as Burkina Faso. With civil unrest happening all around her, Dr. Wilson saw that foreign media coverage was focused on politics rather than on the impact the strife was having on the local people. At that moment, Dr. Wilson knew she wanted to become a journalist.

She pursued a master’s degree in journalism at the University of Western Ontario and by 1980 was a national reporter for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC/Radio-Canada) based in Quebec City, covering the first referendum on Quebec sovereignty. She also covered important stories affecting Indigenous people—stories that would challenge Canadians to face tough issues involving the rights of the country’s First Peoples. A lengthy Radio-Canada labour strike in 1981 prompted a move for Dr. Wilson and her husband, Stephen Kakfwi, to his hometown in the Dene community of Fort Good Hope near the Arctic Circle.

Dr. Wilson found the North rich in stories that needed to be shared with the rest of the country. With her skills as an experienced reporter, she trained community news contributors and encouraged them to recognize the value of their own stories and expertise. As a non-Indigenous woman, she was in awe of traditional northern skills used to make shelter, source clean drinking water and navigate by the stars.

In 1982, CBC launched Northern Canada’s flagship TV current affairs show, Focus North. As its first host, Dr. Wilson helped pioneer the broadcast industry above the 60th parallel. Ten years later, Dr. Wilson became the CBC’s senior manager for northern Quebec and the three northern territories. As regional director, she launched daily television news for Canada’s North, navigating four time zones and 10 languages, the majority of them Indigenous.

She developed the Arctic Winter Games and the True North Concert Series for network television to showcase Indigenous talent. She received a CBC North Award for Lifetime Achievement and the Northerner of the Year Award.

By the time Dr. Wilson left the CBC, nearly half of her reporters were Indigenous northerners.

Because of her expertise in cross-cultural communications, the South African Broadcasting Corporation invited Dr. Wilson to work with their journalists as they brought Nelson Mandela’s dream for democracy to life. Throughout the 1990s, she taught reporters how to hold their new public government to account.

All these experiences would prove valuable when Dr. Wilson, two decades later, bore witness to the stories of Canada’s Residential School Survivors. As one of three Commissioners of the historic Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, she heard horrific accounts of cruelty and abuse from among the 7,000 courageous Survivors. Yet she found a thread of beauty and of shared hope. She continues to lend her voice to encourage all Canadians to explore our past so we can move forward together on a path to national healing.