Building connections

A holistic approach to graduate education

The following is an excerpt. For more on grad student mentoring, see the current issue of TeachingLIFE online.

The “bliss of solitude,” as poet William Wordsworth once rhapsodized, may be lost on the graduate student hustling to meet deadlines, slogging through comps and filing necessary paperwork, all while trying to publish and present their research. Graduate school can be solitary, especially once coursework is completed or if a student is far from home.

Having a mentor can make a huge difference.

One of the key benefits of mentorship is the strong relationship that develops between the mentor and mentee, which may become vitally important to a student.

A supportive environment

A supportive environment

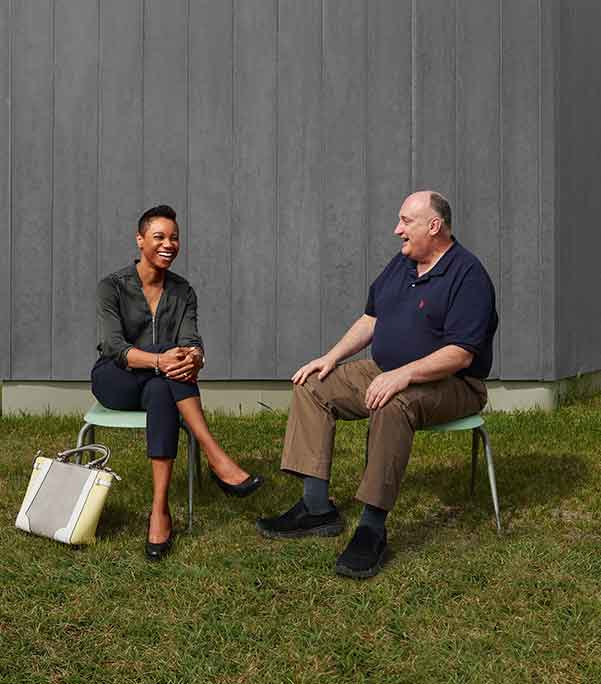

Sean Byrne suggests that good mentors remember the stress of being students. For the past decade, Byrne was director of the Arthur V. Mauro Centre for Peace and Justice. He’s also a professor in peace and conflict studies and a recipient of the 2017 Faculty of Graduate Studies Award for Excellence in Graduate Student Mentoring.

Byrne believes that part of being a mentor is providing “a home away from home,” adding that students may need something as basic as a warm meal or a good conversation. Some students may be facing homesickness, culture shock or personal challenges such as health issues, divorce or even financial troubles. Each student has different needs, but all students need an open and supportive environment to ensure that they are able to be honest about challenges they are facing, whether professional or personal.

Beyond signing forms

For Juliette “Archie” Cooper, professor emeritus, College of Rehabilitation Sciences, mentoring similarly plays a role beyond simply directing students through their thesis or research projects and signing forms.

And being an advisor does not automatically mean that you are or will be a mentor, she notes in her “Mentoring Graduate Students” workshop at the Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning.

Cooper: “Mentors are chosen. You really can’t impose mentorship.”

Cooper suggests encouraging students to approach different people, whether researchers in the field or faculty in other departments. As she puts it, “Mentors are chosen. You really can’t impose mentorship.” The key is to create a collaborative, nurturing environment for students.

Guidance, tangible support and suggestions play a significant role in mentorship. Tenured faculty members may forget how intimidating and challenging it was to be a graduate student learning the ropes, from ordering supplies to presenting at and attending a conference.

Whether it is identifying opportunities, such as publishing or applying for grants or preparing for conferences, a little guidance can make a huge difference, especially to an inexperienced graduate student. Megan Campbell, an M.Sc. student in community health sciences, stresses the importance of those opportunities. Assistance with applying for grants, constructive feedback or contributing a paper can help graduate students build confidence.

Empowerment to join in as a peer

The holistic approach used by her advisor Sean Byrne makes her feel empowered and included in the academic community, says Patlee Creary, who graduated in spring 2018 with her PhD in peace and conflict studies.

When she began her graduate degree, she had a larger concept of her work, but was unsure of what the research project would actually look like. As Creary explains, Byrne “gave [her] room to ask questions and to pursue storytelling [as a method].” She appreciated the respect he showed in providing a complete education experience, encouraging her exploration of different paths and empowering her as a researcher and academic.

Read the rest of the article in the current issue of TeachingLIFE, now online and out in print. TeachingLIFE is an annual publication mailed to U of M teaching faculty and staff.