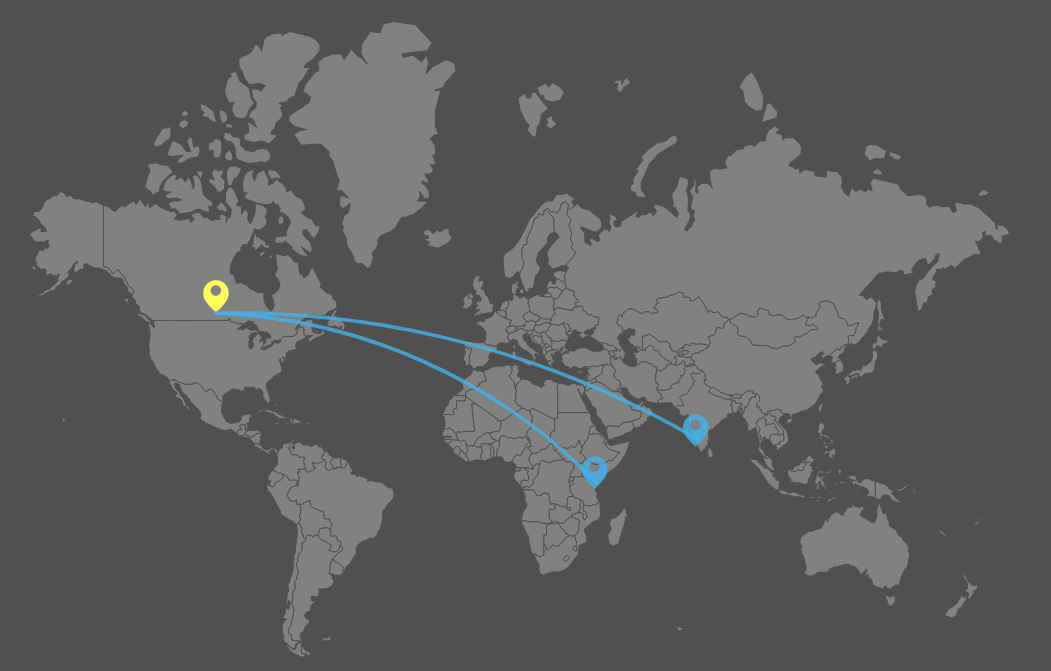

Two of 137 connections across the globe

Q&A with David Barnard on U of M’s international affairs

The University of Manitoba offers a gateway to the world. Every year our International Centre welcomes over 5,000 international students from more than 100 countries to our campuses, facilitates international travel through exchanges and internships, and assists our faculty in finding partners in countries across the globe.

Two projects the U of M is well known for involve our work in Karnataka, India, and in Kenya. But the U of M has a footprint in virtually every country – the latest issue of UM Today The Magazine recently told stories of some of our 140,000 alumni living in 137 countries and the work our researchers do in far-flung places.

Such a global presence can make one ask, why? Why do we do so much work abroad? UM Today sat down with President and Vice-Chancellor David Barnard to get his perspective on the benefits U of M and our community receive from this international reach.

UM Today: What benefits do Manitobans receive from the U of M’s international partnerships?

Barnard: I think from an international research perspective, there are a number of things that directly impact the province, and then there are a number of impacts that are indirect.

To draw from some of our signature areas, for example, with respect to communicable diseases, we had people working in Kenya more than 35 years ago when the AIDS epidemic first broke out. As a result, University of Manitoba scientists were among the first people to witness it and try to figure out what this unknown disease was. That’s had real benefits in terms of developing expertise here: Dr. Alan Ronald and his students, Dr. Frank Plummer and his students. There is a long line of expertise. That’s one of the reasons the National Microbiology Lab was established in Winnipeg.

The collaborative science our researchers do attracts investments and experts here, and we have better, more cutting-edge health care because of it, and more visibility nationally on the health care front. So that’s an example of one.

I think another example from our signature areas is Arctic research. That’s something that clearly matters to Canada. Our people are world-renowned experts—these two areas I mention, there is no question we have world-leading scientists, and that attracts other people here, and it attracts research grants here.

Specifically, what does this mean to the person on the street? Well, in one case, it leads to better health care. In the other, it leads to economic advantage and also to understanding what is happening in the North, which is clearly a really big concern and opportunity for Canada and Manitoba.

So that’s one aspect of international work: what comes back here. But another aspect is what happens when people go abroad. And it’s an amazingly expanding experience. It’s a life-stretching, life-altering experience and people bring that experience back with them.

On that topic then, the U of M sets up labs across the world that we send people to. We have partnerships throughout Asia and the African continent. How do we ensure we do not bring a colonial framework to these relationships?

Allan Ronald, a pioneer in HIV/AIDS research. Credited with helping to create the discipline of infectious diseases at the U of M and across Canada.

I think our people are really good about that. In the areas already mentioned, we’ve had collaborations for years, where our people work with local people. So on the health care front, for example, on AIDS and STIs and mother-and-child care, our researchers and staff work through people locally. Our efforts help set up the offices, but the number of North Americans there is petty small; the number of local professionals and volunteers is much larger.

These relationships have enabled interested individuals from Africa and India, for example, to come here as grad students and then go to these labs to work there. We’ve had medical doctors come here for training and vice versa.

My sense from visiting our partners is that our researchers and staff work exceptionally well at embedding themselves and their staff in the local culture.

The first time I went there, part way through one of the meetings in a clinic in downtown Nairobi, I said, “I just want to ask you a more general question about this work. We’ve been going to places that are really on the margins of society. You go to people who are ill, poor, some are dying from this disease. And yet we walk into these clinics and these people jump up and are happy and giving hugs to you. And you know their names, they know your names. Where does this involvement come from? Where do you learn how to do this level of emotional engagement?”

Plummer sits with his friend Jennifer in Kenya, whom he met in his 17 years working in the country. He met her when she was 17 and diagnosed with HIV. Today she has 3 healthy children thanks, in part, to the work of Dr. Plummer // Submitted photo

A doctor from Kenya, his name is Joshua, said to me, “Well, I was a student of Frank Plummer’s. That what he does and that’s where I learned it.”

And I turned to the other doctor, I think his name was Moses, and asked him where he learned it. And he pointed to Joshua and says, “Well I’m a student of his. I learned it from him.”

What was really clear was this deeply humane contact being passed on from generation to generation. And I think our researchers and staff really have been very sensitive to making it local projects – giving advice and expertise, but embedding the knowledge locally and letting local people lead things.

It’s quite amazing to witness, to see the leadership of local people, and the partnership and the deep, emotional connections between people. I think our people are amazing and I’m proud to be part of the same community with them.

Did you ever go abroad as a student?

I went abroad just before I went to university. I went to Colombia for a summer, part of a church-based team. It was a life-changing experience.

Why do you think students should take advantage of our international opportunities?

Because they provide such a broadening experience. You see how other people live and the circumstances they live in, and you get an appreciation for how, in many cases, our lives here are privileged. And when you do it as part of an academic program, you usually engage in a more substantial way. If you go abroad as a student or professor on sabbatical, you get involved in more depth with the academic life, and you see what it’s like, what another culture offers, what another approach to university can be. It’s just tremendously broadening. You can’t go abroad and not be changed.