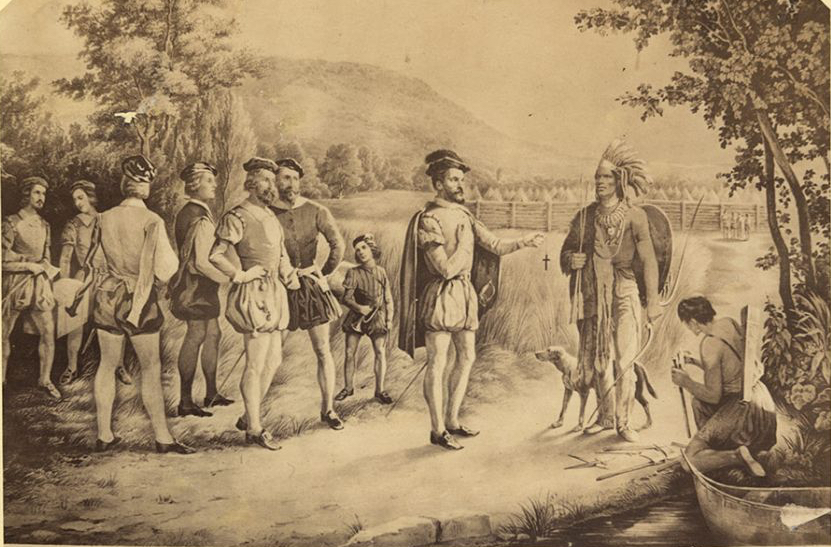

Meeting between Donnacona and Jacques Cartier // Photo: Digital Collection of the Bibliothèque nationale du Québec

Kanata 150+, not Canada 150

The following is an article by Niigaan Sinclair, Associate Professor, Department of Native Studies at the U of M.

You’re going to hear a lot of stories this summer about Canada 150. Go to Ottawa; the entire city is papered with posters, placards, and maple syrup. The entire country is going to join it this weekend.

What you’re probably not going to hear though is the most important story of all. Of the name.

As is with most things Indigenous, you understand the name you understand how to live. The key to this is our languages, which holds a millennia of understandings of how life operates best here.

The fact Indigenous languages are threatened at the same time environmental disaster is imminent and our very lives are at risk is no coincidence.

If you understand the word “Canada,” or rather “Kanata,” you can understand how to negotiate life here. How to grow and build a community. How to live in peace and harmony.

You might even boil some maple syrup once in a while too.

This story doesn’t come from 150 years ago though; it starts with a little meeting almost five centuries ago – in 1534.

Turtle Island in the 16th century was a village made of thousands of villages, a nation of nations. Not perfect by any means, this was a place of large and small governments and communities who worked collaboratively and competitively, trading and warring and sharing and migrating over the seasons and with many reasons. People were travelling all the time, meeting new people, tasting new tastes, witnessing new ways of being, adopting and changing, and so on. It was this way for millennia.

Not one bit of this changed when Europeans arrived. Europeans were just a new leaf on an already existent tree, a knot, a ring in a long series of rings. They certainly were not the whole tree.

One of the first to arrive was Jacques Cartier, who came to North America looking for a path to Asia in May of 1534.

Like so many European explorers, Cartier was terrible at relationship-building. Reaching the eastern shores of Turtle Island, he first encountered groups of Mikmaq and traded furs for metal, the first recorded trade between Europeans and Indigenous peoples this far north. The next day, when more arrived to trade, Jacques commanded his men to shoot at them. Then, he and his men spent a few days shooting over 1000 birds on his way inland.

Like I said, Cartier was a terrible guest.

On July 24, 1534, Cartier travelled to the mouth of Kaniatarowanenneh, later known as the St. Lawrence River, and landed near a village called Stadacona. A few hours later he did what most Europeans did: claiming everything he saw for his King, God, and nation.

He signified this by planting a 10-metre cross in the earth with the engraving “Vive le Roi de France” on it. To him the land was uninhabited, empty, and conquered.

The problem, of course, was that he was standing in someone’s living room. Back yard at least.

Arriving soon after was a Iroquian leader named Donnacona, who had witnessed Cartier’s arrival. Introducing himself as a chief at Stadacona, he asked Cartier what he was doing and gestured that planting a huge monument without permission was a little disrespectful. Some of his men even started to take the marker down. The Stadaconans clearly had law and it dictated that individuals did not simply walk into someone else’s territory and take over the place.

In response, Cartier invited Donnacona onto his ship with the promise of trade.

Accompanied by his three sons and carrying furs to exchange, Donnacona later arrived on Cartier’s ship. He sought from the Frenchmen metal and immediately refused trinkets or decorations. Donnacona knew a trick when he saw one.

Cartier, however, saw an opportunity to achieve the real purpose of his journey: spices and gold. Seizing the moment to get interpreters, Cartier took two of Donnacona’s sons – Dom Agaya and Taignoagny – captive and told the chief they would be returned the following season. For Cartier, profit and resources was the primary reason he came to the New World, not relationships.

Donnacona, likely seeing an opportunity to get a new trading partner, let his sons travel to France, no doubt wondering if he would ever see them again (I have always wondered how he explained this to their mother).

So, Cartier left, traveling up the coastline, searching for spices and gold.

What he found instead were communities who invited him into relationships and didn’t appreciate his obsession with riches.

Returning to France, Cartier turned to Dom Agaya and Taignoagny and demanded his two captives tell him where the riches of North America were.

The boys told him that the riches they knew of resided in “Kanata,” the “great village.” Cartier then marked his map with the name “Canada” and vowed to return to fulfill his vision.

Cartier returned with the young men years later, instructing them to show him Canada. The second the two sons reached Stadacona, though, they escaped from Cartier’s captivity and returned to their father, for the men had reached their riches: their community, their family, their home.

A furious Cartier, in the meantime, continued to look for Canada. The captain hunted furiously, almost succumbing with his men to a scurvy epidemic.

And who saved him? His former captive, Dom Agaya, who returned to feed them cedar tea.

Riches aren’t always spices and gold, I guess.

Still, blinded by dreams of wealth and profit, Cartier continued to search for his illusion. He could not see Kanata for what it is: a place of relationships. Of medicine, healing, and life. Of people. Instead, Cartier saw Canada for what he could take, turn into profit, and sell.

Unfortunately, much of Canada still lives under Cartier’s delusion.

Nowadays we call spices and gold by other names: oil, shale gas, diamonds. Commerce, profit, and exploitation of the land in the name of resource “development” is the foundation of Canada’s past 150 years.

The killing of the birds continue.

Canada’s biggest project has been its manipulation, control, and attempts to assimilate Indigenous cultures and communities. Literally every segment of this country has been built off of Indigenous backs. From the sprawling cities to the national policies Canada “invented” to the very names Canadians carry on their drivers licenses, Indigenous histories are everywhere – even if the textbooks and teachers “forget” to mention this.

Canada was never founded by two nations but hundreds, even thousands, with French and English communities bringing food to an already bustling and full feast. English and French communities are just two new members of a great village, where everyone was welcomed.

This is the story of Kanata. Not Canada, for that place is a fantasy.

We will do well to see Kanata for the riches it is rather then the Canada we think we see, for one is real and the other is an illusion. And, an illusion that is killing us.

The more flags and crosses we drive in the earth to divide ourselves, the more we buy into visions of profit instead of people, and the more we tell one-dimensional stories of one another the less we know about ourselves and our history.

The more we fantasize about ourselves as Cartier’s Canadians and less about who we really are, a great village with riches of relationships, the less we will reach our fullest potential. The riches of Canada lie not in imaginations of gold and spices – and the policies and stories we create from this vision – but in strong, healthy, and equal relationships with people, the land, and the world around us.

That’s the Kanata we deserve to tell stories about.

Miigwech.

Thank you for sharing this history.

It is good to read something off the beaten tracks and that tells historical truth. Thank you for writing this article.

Awesome piece! Tells it like it is. Someday it will be listened to and respected.

Great article

Wonderful article! I have felt badly that the indigenous people have been ignored. I was drawn into the misconception that the residential schools were a good thing but at the same time my heart cried for the separation of children from parents not even realizing the additional problems of abuse! I’m glad to hear of so many well spoken indigenous people who are able to tell their stories on the CBC radio. I’m a 72 year old grandmother of 10 grandchildren 6 of whom are part indigenous.

I love this written piece Niigaan. Truth must be told. Our Grand Children is who I see. As our Grandparents wanted for us, so too, do I want good truth for those yet to be born.

Chi-miigech Aawendaan.

Very illuminating