Frank Hawthorne // Photo by David Lipnowski

A true renaissance man

There’s an art print hanging prominently in the office of Frank Hawthorne, tucked away in a back hallway on the fourth floor of the Clayton H. Riddell Faculty of Environment, Earth, and Resources. The title is Knight at the Crossroads, painted by Russian artist Viktor Vasnetsov in 1878. It currently hangs in The Hermitage in Moscow, a gallery Hawthorne has visited half a dozen times.

“It made an impression on me,” says Hawthorne. “The knight has a choice which way he wants to go: one way to the farm, and the other to the battlefield.” He adds: “I was thinking about retirement when I saw that.”

Almost 70, Hawthorne’s career has taken him to the pinnacle of his field, having achieved prominence few others can claim. In 2007, Thomson Scientific, a leading information company, analyzed data from 150,000 scientific papers published between 1997 and 2007, noting that Hawthorne was the most-cited geoscientist in the world, with 2,204 citations during that period alone.

“I hadn’t realized there were that many,” he says modestly.

Hawthorne was born in England in 1946, trained at the Royal School of Mines, Imperial College in London, and then at McMaster University in Hamilton. He was a post-doctoral fellow and later held a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) University Research Fellowship (URF) from 1980-1990 at the University of Manitoba. In 2001 he was appointed Canada Research Chair in Crystallography and Mineralogy and is now distinguished professor in geological sciences.

Hawthorne has been described by students and colleagues as a “rock star” because of his work in geology, of course. In fact, he takes the joke in stride; his office is adorned with posters of Pink Floyd, The Who and The Rolling Stones. He admits that he’s a fan of early rock and is fascinated by the history of “beatniks” like himself.

This may seem in sharp contrast to someone who is an Officer of the Order of Canada, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, a Foreign Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and someone who has received a multitude of awards for his scientific work, including the Killam Prize in Natural Sciences.

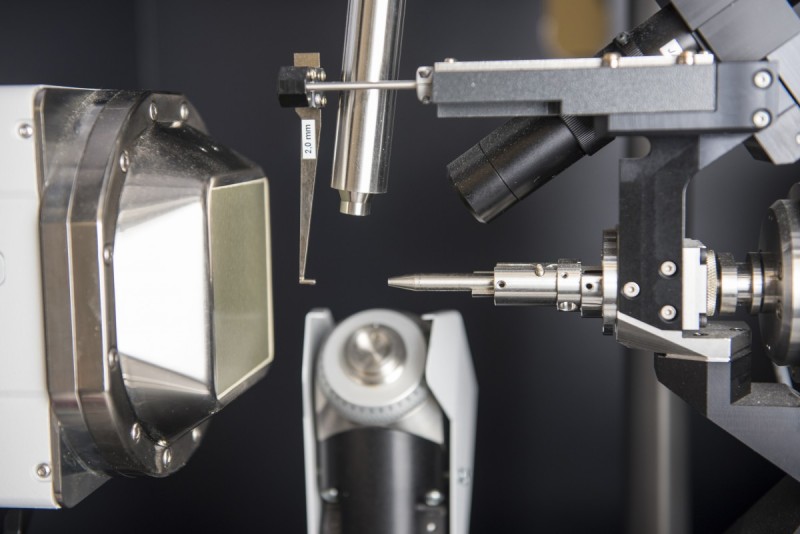

The “rock” designation is somewhat ironic because Hawthorne’s work has little to do with a chunk of granite from the Rockies or a pebble found on a beach. His research instead focuses on understanding the atomic structure of minerals, using advanced mathematical concepts such as topology and graph theory to determine how materials are assembled at the atomic scale.

In fact, his desire to quantify the atomic structure of minerals was what led to his invitation to become a Foreign Member of the Russian Academy of Science, an honour bestowed on very few. He was giving a talk in Moscow when the vice-president of the Russian academy heard him and admired his quest to inject rigorous mathematics into the geological sciences. Hawthorne was soon elected to the academy because of his work on the foundations of mineralogy.

“It’s an accolade that completely outdoes everything else,” Hawthorne notes.

That in itself is remarkable because Hawthorne has achieved such respect in his field that a mineral has been named after him: frankhawthorneite. (It’s a rare, green, copper-based mineral discovered in Utah in 1995.)

Hawthorne is personally interested in solving a problem that seems basic to all branches of science: “Why is that the way it is?” he wonders: “How do atoms come together to form solids, and can we manufacture or design new materials by arranging atoms differently?”

He points to solid state electronics that are doped with various atoms to modify and improve their characteristics, and modern high-temperature ceramics that have been developed in the laboratory to make them usable in the average home oven.

“I want to understand the chemical compositions and atomic arrangements of minerals,” he explains. “Studying three-dimensional arrangements of atoms is fascinating to me.”

Hawthorne says his research isn’t confined to his laboratory or calculations with matrices. He believes firmly in interactions with other researchers around the world.

“It’s not just going to conferences and presenting or listening to others lecture,” he says. “It’s talking with others and getting to know them and their work.”

“Café conversations are the best,” he says, smiling.

And then, there’s his non-work time, which he values highly.

“I need time by myself, just to think,” he notes. He’s spent much time in museums and art galleries around the world, like the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg in which he was enraptured by Knight at the Crossroads.

He enjoys Renaissance and Baroque art and has spent enough time in Italy that he’s “almost fluent” in Italian. He appreciates opera and other

artistic works such as sculpture and poetry.

“An artist can reach out and speak to me,” Hawthorne says poignantly. “I can look at a painting by Caravaggio and it seems as though he’s talking directly to me.”

Hawthorne may have found the ideal balance between science and art. He may deal with abstract mathematics, but he can envision the formulae creating physical structures and materials that can be used or appreciated by others.

“Science doesn’t have the personal aspect that is inherent in art,” he states, “because science is a collaborative and collective activity.”

“But both are intellectually satisfying,” he adds.