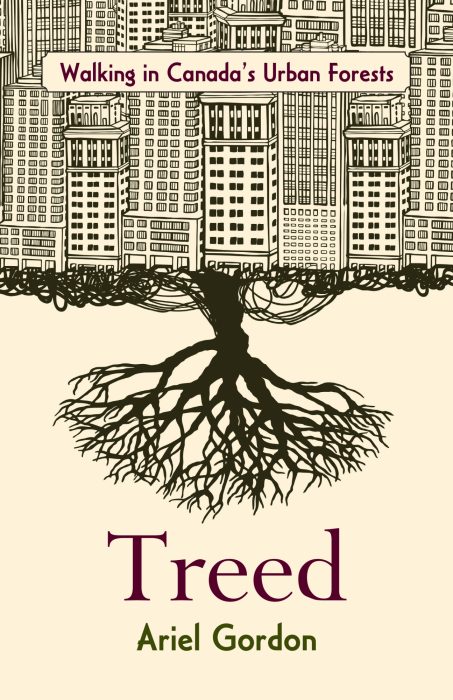

Southwood lands. // Photo: Ariel Gordon

A treed life

Ariel Gordon, who usually helps launch University of Manitoba Press books, has launched her own book exploring Winnipeg’s urban forest.

Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests is the latest project from the award-winning poet and in it she takes readers across the country, from the U of M campus to Banff National Park to a ranch in Langruth, Manitoba, sharing stories of the lives of trees and the creatures that depend on them.

On July 20, Gordon will be leading a guided forest walk in Assiniboine Forest that features forest bathing techniques and finish with tea and a book signing. (Learn more.)

Here is an excerpt from an essay set in the University of Manitoba’s Southwood Lands called “The Social Life of Urban Forests”:

April 2018. I’m walking through the Southwood Lands, a decommissioned golf course next to the University of Manitoba. The first settler use of the land was the Norwood Golf Club, founded in 1894. Six years later, it became the Winnipeg Hunt Club, with stables, kennels and hounds imported from England, as well as a luxurious clubhouse. After World War I resulted in a shortage of hunters to go with the shortage of local game, the seven-hole Winnipeg Hunt Golf Club was built. Another parcel of land was purchased from the university for an eighteen-hole course, which was built around 1919 and renamed the Southwood Golf Club.

April 2018. I’m walking through the Southwood Lands, a decommissioned golf course next to the University of Manitoba. The first settler use of the land was the Norwood Golf Club, founded in 1894. Six years later, it became the Winnipeg Hunt Club, with stables, kennels and hounds imported from England, as well as a luxurious clubhouse. After World War I resulted in a shortage of hunters to go with the shortage of local game, the seven-hole Winnipeg Hunt Golf Club was built. Another parcel of land was purchased from the university for an eighteen-hole course, which was built around 1919 and renamed the Southwood Golf Club.

The University of Manitoba bought the land in 2011 and intends to develop it, but until that happens, they’ve renamed it the Southwood Lands and have allowed its use as a park, to the delight of commuting students and dog walking, skiing and cycling locals. The path I am walking, broken through the last of the snow, leads me to a spot where two trees have been cut down this morning.

I approach the closest one. There is sawdust on the gritty ice and snow. Sawdust on the half-frozen grass, unearthed by steel-toed boots and machines, but still surprisingly green. The trunk of the tree, as wide around as a barrel, is cut into manageable chunks and laid on the ground nearby, like a sushi roll cut into pieces.

I’d known these trees were going to come down. They’d been part of a trio, planted in a line near a path that went through the trees and emerged onto the greens and fairways that are the bread and butter of a golf course. A month ago, when everything was starkness, white snow and black limbs on bare branches, I’d come out of the trees and seen that two of the three had orange dots on them.

I appreciate colour in winter: the red bark of dogwood branches, the orange berries of mountain ash or the orange- red of overwintering rosehips. But these blots of colour only mean one thing, a DED diagnosis. A death sentence for the trees.

Today, those blots are gone. All that’s left are fresh stumps, two and a half feet across. Trees that were seventy-five or a hundred or 120 years old. Two trees that had been a part of the approximately 230,000 elms in Winnipeg’s urban forest.

These trees are part of the monoculture of elms (and ashes and oaks) in our canopy. And even if there’s an elm tree on every block, even if they’re ordinary to us, taken together, these trees are a rarity, part of the largest population of American elms remaining in North America. I want to honour them somehow.