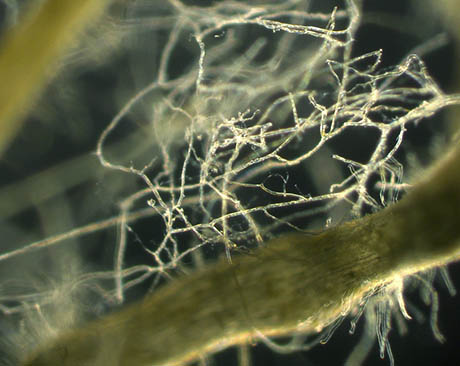

Photo: Natural Resources Conservation Service Soil Health Campaign

What organic soils and teenagers have in common

For healthy results, you have to force them to look after themselves

The United Nations has declared 2015 the International Year of Soils. Soils are overlooked and underappreciated by many, but healthy soils are crucial to all terrestrial life. UM Today has celebrated soil already, and now it examines how soil can impact our food.

When deciding to buy organic or non-organic food, consumers should ponder more than just pesticides because research shows healthier soils makes healthier foods, and well-managed organic soil is much healthier than soil on conventional farms.

Discovering that well-managed organic farms (and there are plenty of poorly managed ones) have healthier soils surprised researchers like Martin Entz, a plant scientists who operates Canada’s longest-running organic-versus-conventional crop system study at the University of Manitoba’s Glenlea Research Station.

Compared to the soil of conventional agricultural systems that rely on fertilizers, the soil of well-managed organic agricultural systems harbours more life such as bacteria, fungi, and worms; all desired stuff. Why? How?

What Entz and others learned is that soil – like teenagers – will eventually learn to do something if left on their own.

“We thought fertilizers were always helping soils build up their health,” says Entz, a professor in the Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences. “But what we’re learning now, especially with phosphorous, is if we restrict that nutrient a little bit, we actually wake up the soil biology. We force it to actually look after itself.

“It’s kind of like cleaning a teenager’s room: if you do it for them, they never will. But if you are patient with a messy teenager for a time, and coax them, eventually they learn to clean their own room. So interventions that appear practical and make the visitors to your house happy, may actually not be good for the teenager in the long run. And the same is true for soil: if we keep putting in high-energy fertilizers into the soil, we’re making it lazy. That’s what was surprising: That less is more.”

To have a well-managed organic system, the farm needs plant diversity. Soil microbes, like humans, need to eat their veggies and the only way to get more food into the soil ecosystem is to grow more plants. This idea is spreading across Canada. Visit an apple orchard or wine vineyard in Ontario and you won’t likely find well-groomed grass between neat rows of trees or vines. Instead, you’ll see a cocktail of different plants growing between the rows that will change every year, offering a different menu to soil’s microscopic life.

All microscopic life in soil is important but a specific fungus has a particularly big role to play. Living inside the roots of most plants is mycorrhizal fungus, a master of absorbing micronutrients like zinc and iron into the plant. But in heavily fertilized fields, Entz has found, the fungus resigns from its nutrient gathering duties, passively absorbing fewer fertilizer nutrients instead of aggressively finding more for itself.

“The data is pretty clear on this,” Entz says. “Organic foods in well-managed systems have more micronutrients, and a better balance of micronutrients, which may be just as important. It’s more nutritious food and for years people poo-pooed the idea that organic foods can be more nutritious, but studies are showing this to be the case – again, in well-managed organic systems.”

Another benefit is that when the soil is more biologically active, it communicates with plants in new and interesting ways.

Soils constantly “talk” to plants. Bacteria produce chemicals that switch on genes in plants. A classic example is a cover crop called vetch. It switches on a self-defense mechanism in tomatoes, making them much less susceptible to diseases. What’s more, biologically active soil triggers plants to produce more compounds beneficial to humans, like antioxidants.

Why then are conventional cropping systems still so popular?

“I think because you can intervene and deal with unexpected circumstances very quickly,” Entz says. “If you have an insect attack, you can just spray insecticide. If you have a deficiency of a particular nutrient you can fix that within 10 days with a fertilizer. That’s why we went down that road and invented all those things: farmers needed tools to fix problems. “

The problem, Entz says, is we have taken this to the extreme and farmers now need to constantly intervene, spraying more agents more frequently just to keep the system running. But things may be on the cusp of changing.

“I think a general recognition in the agricultural science community is that we have to get back to looking at how we make soils healthier to allow all these benefits to cascade from a healthier soil into rest of the system, including the food…. We’re not going to be able to intervene as quickly as just putting fertilizer down to fix a problem. But because we understand the ecology of the soil – and the organic community has to understand it the best – we can design that system to avoid the problem in the first place. Organic agriculture builds soil for preventative medicine.”

Interested in learning more?

The Glenlea Long-Term Study Field Day will be held Wednesday, July 8, at the Glenlea Research Station at 1:00 p.m. Tour begins at 1:15 p.m. sharp. The focus of the day is “Designing productive farming systems that require fewer fertilizer and herbicides”. Topics include lessons from the 24-year-old Glenlea crop rotation study including alternative weed and soil fertility management practices, direct seeding wheat using mulches instead of glyphosate, inter-row tillage for small grain production, making nutrient-rich compost from farm and urban waste, soil health measurements, and oat variety development for organic and ecological production. Visit the website for all tour details.

The Ecological and Organic Farming Systems Twilight Tour will take place Wednesday, July 15 at the Ian N. Morrison Research Farm in Carman, MB. At 5:30 p.m. there will be a free BBQ and meet and greet and then 6:30-8:30 pm is the tour. Topics include new organic seed quality research, organic soybean variety test, organic food grade corn production (a first in Manitoba!), evaluation of farmer-selected wheat and oat varieties – see how farmer-bred varieties compare to popular wheat and oat check varieties, and tools and ideas on how to conduct inter-row tillage for weed control in small grain production. Visit the website for all tour details.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.