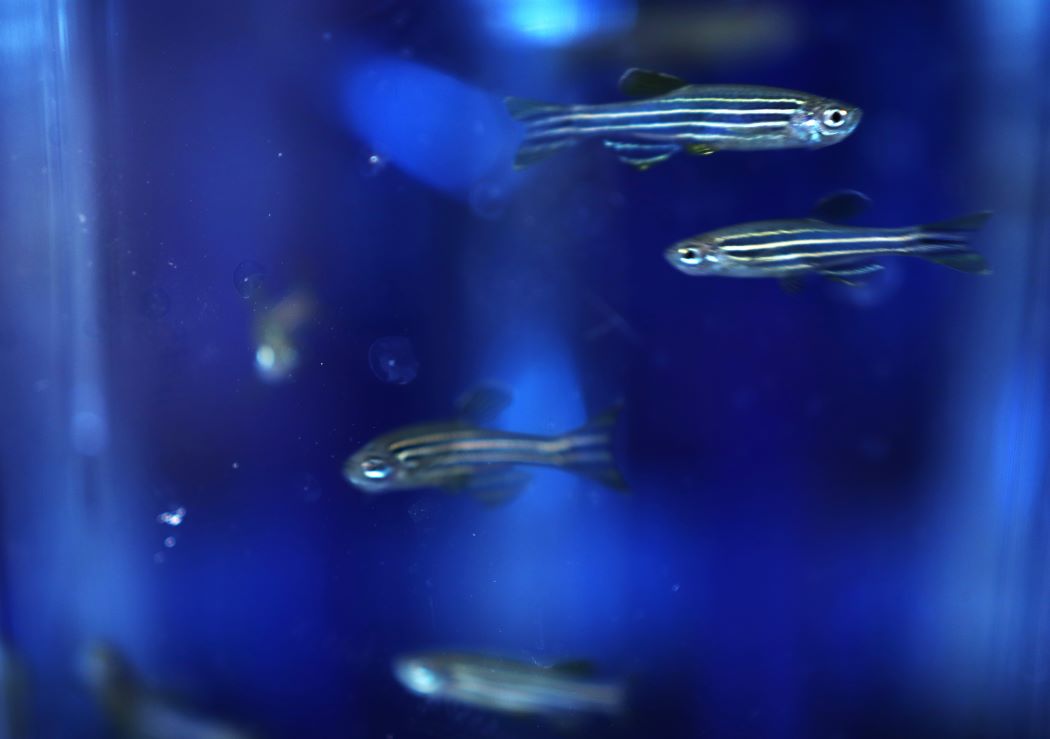

Zebrafish, which are used worldwide in biomedical research, can serve as a model for many human diseases, including cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

UM unveils new research facility where tropical fish shed light on human health

At the official opening on Nov. 18 of a $2.5-million facility on UM’s Bannatyne campus, scientists showed off laboratory animals with surprising potential for biomedical research: tropical fish.

The new Rady Biomedical Fish Facility in the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences is outfitted with cutting-edge equipment for studying two freshwater species: zebrafish and Mexican tetra fish.

Among the qualities that make these vertebrates fascinating to researchers is their capacity to regenerate body parts. If they’re injured, they can heal themselves.

They also grow and shed many sets of teeth over their lifespan. Genetic understanding of this ability might help pave the way for dentists of the future to regenerate patients’ teeth.

“We are honoured to be part of this world-class research facility,” said Jennifer Cleary, CEO of Research Manitoba, which contributed to funding the new equipment.

The facility, located in the basement of the Chown Building, currently houses about 2,000 zebrafish and 250 Mexican tetras. The fish tanks are stored in a state-of-the-art, multi-rack holding system that automatically maintains every aspect of water quality.

The Rady Biomedical Fish Facility was spearheaded by two scientists who are co-leading it: Dr. Devi Atukorallaya, associate professor of oral biology at the Dr. Gerald Niznick College of Dentistry, and Dr. Benjamin Lindsey, assistant professor of human anatomy and cell science at the Max Rady College of Medicine.

“We now have the most advanced facility for small laboratory fish on the Prairies, in terms of equipment and technologies. We’re leading players in this,” Lindsey says.

“We encourage other Manitoba scientists to learn about the potential of these animals for health research and collaboration. One advantage is that fish are more cost-effective for research than small mammals, such as mice.”

“The developmental genetic pathways in these fish are remarkably similar to those in humans,” Atukorallaya notes. “About 70 per cent of the genes are the same as human genes.”

Dr. Devi Atukorallaya

Atukorallaya, a dentist and scientist, is the only researcher in Canada using the Mexican tetra species for biomedical research.

She conducts experiments with both Mexican tetra and zebrafish to gain insight into skull and facial development in human embryos. “The fish embryos are transparent, so under the microscope I can study how the bones, teeth, organs and sensory systems develop. This helps us to understand human congenital malformations, such as cleft palate.”

The Mexican tetra species has evolved into two types that are of great genetic interest: pale-coloured cave fish that have no eyes and an abnormal face shape because they live in total darkness – but have other highly developed senses – and surface-dwelling fish that do have eyes.

Atukorallaya has several research projects underway. In one, she has been the first in the world to expose fish eggs to alcohol in order to study abnormalities of tooth and tastebud development that correspond to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in humans.

Zebrafish are used worldwide in biomedical research, Lindsey says. They can serve as a model for many human diseases, including cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

Lindsey, a neuroscientist, is one of a handful of Canadian researchers using zebrafish to study brain and spinal cord injury. His focus is on investigating the species’ extraordinary ability to self-repair.

Dr. Benjamin Lindsey

“The neural stem cells in zebrafish are very good at regenerating tissue after trauma. If we can discover how they do this, it could one day lead to treatments for humans with brain injuries or neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s.”

When Lindsey’s team works with zebrafish, different parts of some fish are “tagged” with harmless fluorescent colours that allow the researchers to see cells of interest in the brain or spinal cord.

Lindsey is also interested in using fish to study the plasticity of the brain – its capacity to “rewire” its networks.

The Rady Faculty of Health Sciences invested about $1.5 million into renovating the facility space. The equipment was funded by joint grants received by Atukorallaya and Lindsey from the Canada Foundation for Innovation John R. Evans Leaders Fund and Research Manitoba ($843,000) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council ($90,000).

The features of the Rady Biomedical Fish Facility include:

- Incubators for fish eggs;

- A high-end confocal microscope that captures fluorescent images of fish;

- A micro-injection station that enables researchers to inject fish or larvae with tiny volumes of chemical solutions;

- A system for studying the behaviour of adult fish or larvae that includes video cameras to record the animals’ movements, plus sophisticated software that analyzes variables, such as the speed of swimming or an aversion to bitter-tasting food. One application of this setup is to study fish learning and memory.

Watch an Instagram video about the fish facility opening.