Jen Sebring at the University of Manitoba's Bannatyne campus, standing beside a collage of participant-created artwork.

Turning illness into art: PhD student uses art to transform chronic care

Most people wouldn’t think of art to address chronic illness. But for Jen Sebring, a PhD candidate at the College of Community and Global Health (CCGH) in the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, art became a powerful and thought-provoking tool to better understand and support those with chronic health conditions and disabilities.

Drawing from their own lived experience, Sebring brings firsthand insight to the challenges of chronic illness. Their research focuses on functional neurological disorder (FND) – a condition that causes multiple neurological symptoms without a clear medical cause.

“I was appalled by my experiences as a patient trying to find a diagnosis and how difficult it was to get the care I needed for debilitating neurological symptoms,” they said. “At the same time, I was also fascinated by what I was learning about the brain and how these symptoms manifest.”

As they learned more about FND, they were inspired to focus their research on supporting others with FND and involving the community in improving care.

Sebring said no research currently exists on the experiences of people with FND in Canada. They hope their work will change that.

They completed an undergraduate degree in women’s and gender studies at the University of Winnipeg before pursuing their master’s and PhD at UM. Sebring is a 2022 Vanier Scholar and 2025 Research Manitoba PhD studentship recipient.

Sebring shared more about their journey in community health and how art became central to their research.

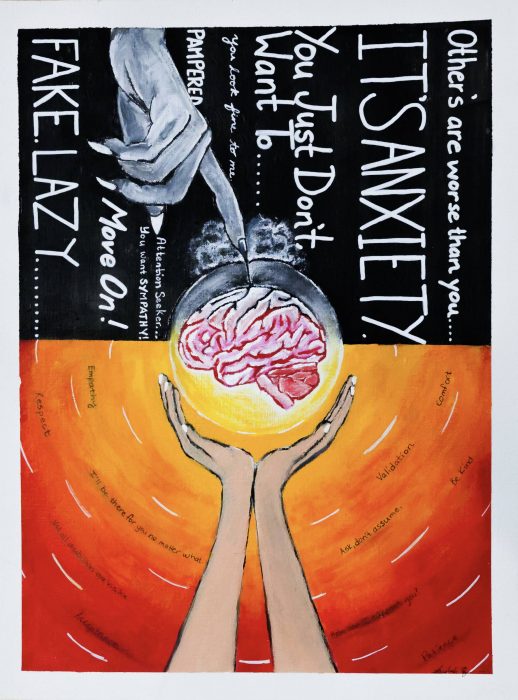

“Lift the Weight or Deepen the Wound” by Vaishali Sharma

What challenges do people with FND face that make it different from other conditions?

FND symptoms can range from cognitive issues – such as memory and concentration problems – to speech disorders, limb weakness and seizures. These conditions can be quite unpredictable, and health-care providers may know little about them.

Patients often struggle to access care, frequently shuffled between specialists without clear direction. Some physicians refer patients to psychiatrists, who then send them back to neurologists. This referral pattern creates a cycle of confusion and stigma.

They’re not considered high priority, even when FND affects their daily lives. Many are accused of faking their symptoms because test results show nothing abnormal.

Can you tell us more about your research and how it can impact health care?

I conduct qualitative research with people living with FND across Canada, using interviews, conversations and art-based methods.

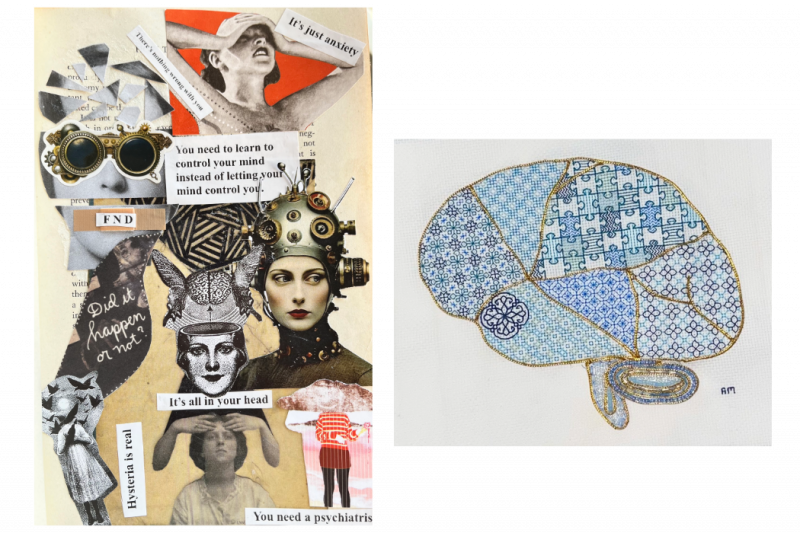

Participants first share their experiences with the health-care system through interviews. Then, they take part in a six- to eight-week workshop where they create art that reflects their stories. This approach gives us rich insights – often ones we wouldn’t have come across through interviews alone.

My goal is to raise awareness in the medical community and ensure patients’ perspectives are reflected in research and health-care education. By centring their voices, we can create meaningful change that addresses their needs and concerns.

Left, “It’s All in Your Head” by Bronwyn Berg; right, “Une connection à la fois” by Amélie M.

How has the College of Community and Global Health supported you in your learning?

It’s been a great college to be in because we get a solid grounding in health research, our health system and all these different dimensions of what that research can look like. CCGH has been very open-minded since my study isn’t what typically comes to mind when people think of health research.

I’ve also received mentorship, travel funding and other forms of support. Those resources have helped me pursue different professional opportunities, which has been exciting.

What’s next?

I recently launched a website featuring artwork created by research participants, where health-care providers and Canadians can learn from their experiences.

My next project will explore what recovery looks like for people with FND, including the creation of visual timelines that map their journeys. I’m also envisioning an interprofessional health education initiative – training health professionals across disciplines to better support those living with FND.

Through my continued commitment to this community, I hope to shed light on the realities of FND and help patients access the care they deserve.

***

To learn more about Sebring’s research, visit: undoingdisorder.ca.