Rate of children diagnosed with type 2 diabetes rises over 50% over last 10 years, MCHP study finds

First Nations individuals twice as likely as all other Manitobans to be newly diagnosed

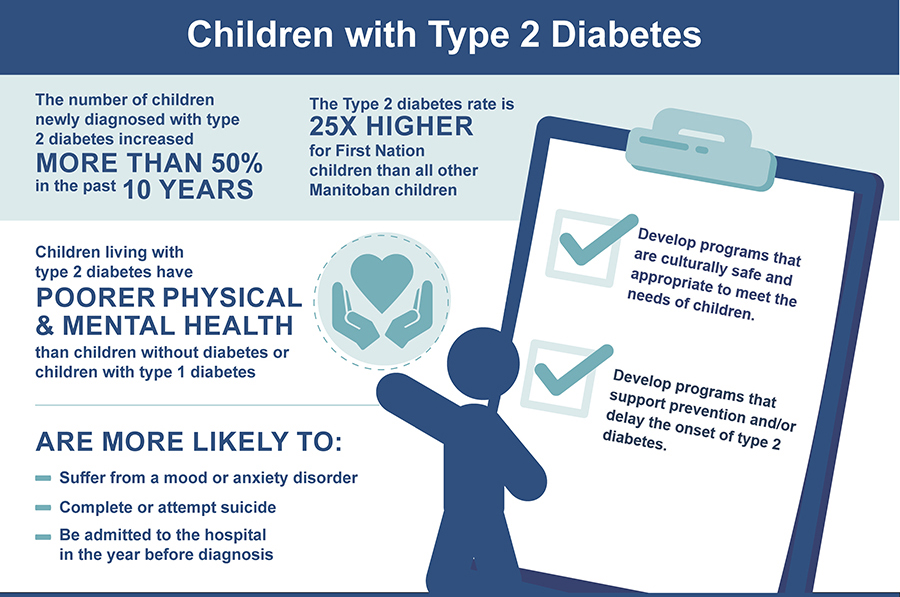

Once thought of as a disease affecting mainly older adults, type 2 diabetes has been on the rise among younger people in Manitoba. In the last decade, the number of children in the province diagnosed with type 2 diabetes has risen by more than 50 per cent, and the rate of diagnosis is even higher in First Nations communities, according to a new study from the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) in partnership with the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba (FNHSSM).

The report found that children in First Nations communities are 25 times more likely to be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes than other children in Manitoba.

“Type 2 diabetes is increasing in all populations in Manitoba, including children, but the numbers are disproportionately high for registered First Nations children,” said Dr. Chelsea Ruth, assistant professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Manitoba, and one of the study’s co-leads.

She said First Nations individuals are accessing primary care at a similar rate as all other Manitobans, but noted that care is not reducing the complications from type 2 diabetes, such as leg and foot amputations and kidney failure.

“There is this prevailing belief that First Nations individuals have more complications because they’re not accessing health care, but this report actually shows they’re receiving health care in the same numbers but the care received is not adequate to fit their needs,” she said, citing the impact of systemic racism and colonial laws. “First Nation individuals also saw specialists at lower rates than all other Manitobans, which may contribute to worse outcomes. This lack of equity needs to be addressed.”

Ruth also noted many Manitobans are not receiving the care recommended by national guidelines to prevent complications. She said a screening that should be done annually to discover early kidney disease is by 63 per cent for First Nations Manitobans and only 53 per cent of all other Manitobans.

The report, which used multiple data sets from the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository at MCHP to identify Manitobans living with the disease, urged that type 2 diabetes care cannot have a one-size-fits-all approach, especially in First Nations communities, which need strategies that work for their unique needs.

The study also said that as the age of people being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes decreases, more women will go through pregnancy with the disease. Over a six-year study period between 2011 and 2017, there were 2,283 infants born to women with type 2 diabetes in Manitoba, about half of which were born to First Nation women.

“Pregnant women with type 2 diabetes are three times more likely to be hospitalized than those without diabetes, and their babies are four times more likely to be admitted to intensive care,” Ruth said.

The report recommends expansion of neonatal and prenatal care in hospitals close to rural communities where many women with type 2 diabetes live, to allow for prenatal hospitalizations and care of late premature infants.

About 109,000 Manitobans have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, and more people are diagnosed with the disease each year. Type 2 diabetes is an illness that develops when the insulin your body produces is not working well and/or when your body does not make enough insulin. The sugar in a person’s blood is not taken up by the cells that need it for energy, resulting in higher than usual amounts of sugar in the blood.

The disease has often been naively associated with lifestyle choices, leading people with the illness to blame themselves while health-care professionals fail to look for other solutions, said the study’s primary investigators.

“The health system has made it the responsibility of the client with this simplistic idea that if you live healthy, eat healthy, and exercise, you’re less likely to have type 2 diabetes. We know there’s more to it than that,” said Lorraine McLeod, associate director of the Diabetes Integration Project (DIP), FNHSSM. “As health care providers, we really need to provide care that is non-judgemental and client focused. The health-care system has a responsibility to support and ensure the delivery of high quality and culturally safe care.”

Dr. Elizabeth Sellers, a UM professor of Pediatrics and Child Health, said DIP is one positive solution to addressing type 2 diabetes in First Nation communities. Another is Wijii’idiwag Ikwewag: Manitoba Indigenous Birth Helper’s Initiative, which promotes traditional Indigenous child birth and parenting teachings in Manitoba.

“These targeted initiatives have been incredibly positive. We saw a high level of eye and kidney screening in the Northern Regional Health Authority, where these programs are,” she said.

The full study is available here: http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/health_sciences/medicine/units/chs/departmental_units/mchp/Landing_T2DM.html