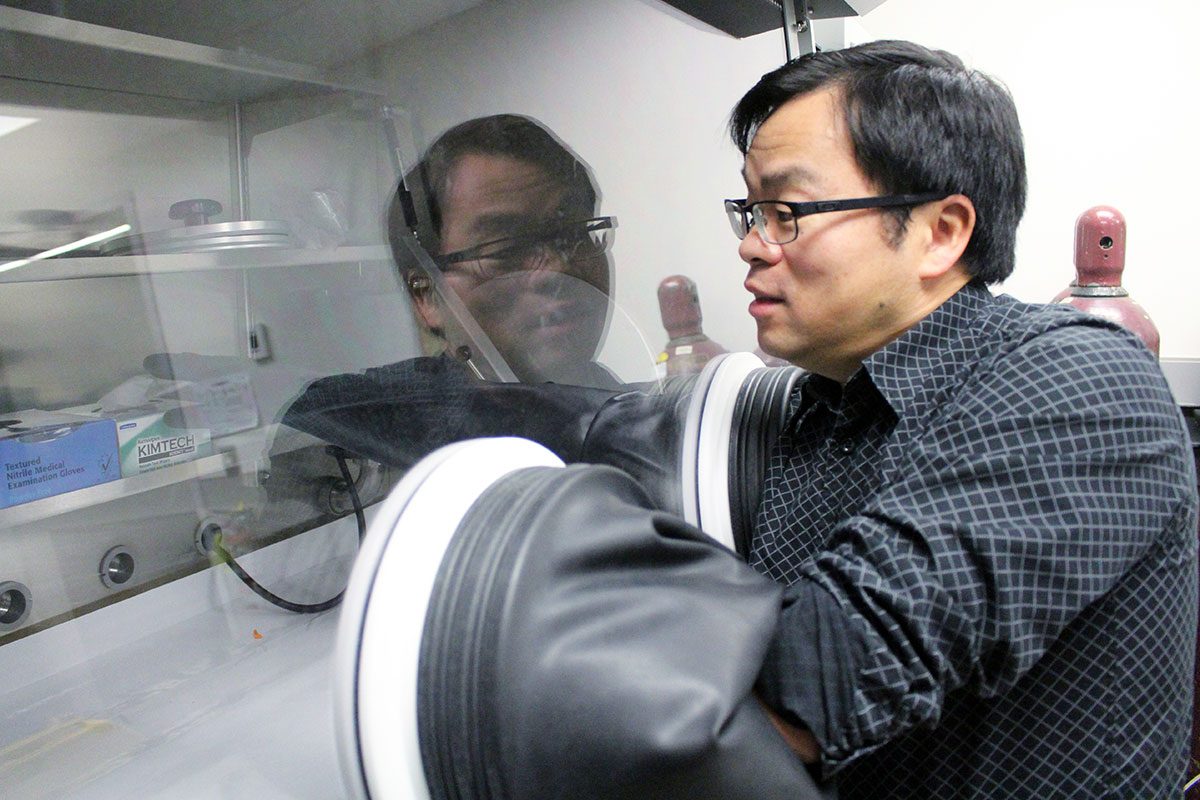

Feiyue Wang uses a glove box in his lab, allowing him to work with samples sensitive to oxygen. // Photo by Kaitlin Vitt

Professor leads the way in Arctic environmental chemistry

A cold lab in the Wallace Building at the University of Manitoba’s Fort Garry campus allows scientists to conduct Arctic research all year round. The lab has rooms of different temperatures, -4 C, -20 C and -40 C. To work in the cold lab, researchers bundle up, wearing gloves and winter parkas, just like they do when in the field.

“We started to wear Canada Goose a long time ago,” Feiyue Wang says. “In the last five years, suddenly it’s become very fashionable. Everyone is wearing them.”

Wang is a professor of environment and geography at the Centre for Earth and Observation Science in the Clayton H. Riddell Faculty of Environment, Earth, and Resources. He was recognized Dec. 9 for being a leader in more than just the fashion world. He was named a Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in Arctic Environmental Chemistry, receiving $1.4 million over seven years to support his research.

Quite a few Canada Research Chairs have mentored Wang, and he says he’s thrilled and humbled to be named one himself. When he heard the news, he says he sent an email to his current and past students.

“They are the ones who make me look good,” he says.

Arctic impact

Wang is looking at chemical processes happening in the cryosphere — the frozen parts of Earth, like snow, sea ice and permafrost — and what their implications are.

“We always think once you freeze your stuff, nothing happens,” he says. “That’s how we keep our food in the freezer and so on.”

But as it turns out, there’s more to it.

Because of the high concentration of salts, frozen sea ice has different properties than frozen lake ice. When seawater freezes, it doesn’t become a solid piece of ice — a small amount of liquid remains, filling the space between ice crystals.

Salts and contaminants concentrate in these pockets of water, which can result in unusual chemical processes. These processes may change the cycling of contaminants, like mercury, making them more prone to deposition in the environment and accumulation in organisms. Or sometimes these brine channels create products, such as ikaite, a mineral that acts as a new pathway for carbon dioxide exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean.

We need to understand these processes so we know how to clean up contaminants like oil spills in the Arctic, Wang says. So far, technology to clean up oil spills is used in open oceans, not oceans covered in ice. Wang and his team need to determine if the same processes can be used in either place.

“Working in the environmental field… we’re driven by curiosity, but we’re also driven by real world problems and problem solving.”

Feiyue Wang was named a Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in Arctic Environmental Chemistry Dec. 9. // Photo supplied by Feiyue Wang

Wang has travelled on the CCGS Amundsen, the icebreaker on the Canadian $50 bill. There are labs where researchers can conduct experiments right on the vessel after collecting samples in the field.

Besides fieldwork and using the cold lab, Wang does research at the Sea-ice Environmental Research Facility (SERF), originally constructed with funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the Province of Manitoba, located in Smartpark, the university’s research and technology park. He calls the large inground outdoor pool at SERF a “big beaker.” This is where his team conducts experiments, like growing and monitoring sea ice under controlled conditions.

Since Wang started working at the U of M in 2000, his research has focused on mercury as a contaminant, particularly in the Arctic. People living there rely on marine mammals as part of their diet, which can have high concentrations of mercury.

Thanks to Wang and other researchers, there is now an international treaty, the Minamata Convention on Mercury, protecting people and the environment from anthropogenic emissions and releases of mercury. To date 128 governments, including Canada, have signed the treaty.

In terms of further mercury research, Wang’s team will focus on whether or not the environment will recover after past mercury contamination, and if it can, how long will it take.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.