Demonstration at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, D.C., during the influenza pandemic of 1918 // Photo: Library of Congress

Pandemic parallels: UM expert compares Spanish flu and COVID-19

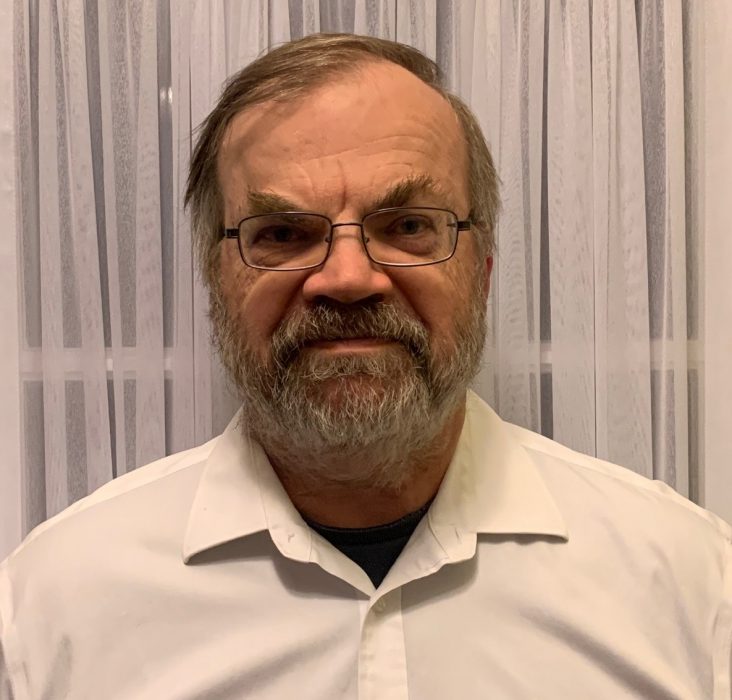

A Rady Faculty of Health Sciences professor with experience studying the Spanish flu says there are parallels between the deadly virus from 1918 and today’s novel coronavirus, and he is hopeful a vaccine will be developed.

Dr. Kevin Coombs, a professor in the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases, Max Rady College of Medicine, researched the Spanish flu for a study that was published in EBioMedicine in 2018.

The study compared how Spanish flu reacted and the types of proteins it affected in cells compared to other mild or highly pathogenic viruses. The research team, which included Dr. Darwyn Kobasa, Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and Dr. Charlene Ranadheera, PHAC, noticed that the Spanish flu affected many proteins not identified in other studies.

Dr. Kevin Coombs said we’re in a much better position today to mitigate a pandemic than those living 100 years ago.

“Spanish flu disrupted one particular pathway more than the other viruses, including bird flu, so this ties in with the fact that not only was the virus pathogenic, but it was able to spread to so many different people.”

It is estimated that the Spanish flu infected approximately 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population. The virus caused at least 50 million deaths around the world.

Coombs said there are several parallels between the Spanish flu and today’s novel coronavirus. Both viruses cause cytokine storm syndrome, a complication in which the body overreacts to the virus, and this overreaction does more harm than the virus, Coombs said. He added that the viruses were both brand new, so the majority of the world’s population had no antibodies against the viruses. Both are also respiratory viruses and are highly infectious, he said.

“It’s still early days but the case fatality rate appears to be a bit higher for COVID-19, but the infectivity for the Spanish flu – the capacity for flu to spread – is a little bit higher than it is for COVID-19,” Coombs said. “Now whether those will equal out in the long run we still don’t know.”

Because the Spanish flu happened more than 100 years ago, Coombs said they are relying on reports and accepting that the information collected back then is accurate. He said that it took much longer for people in 1918 to practice social distancing. Not only have we adopted the practice sooner, he said we’re in a much better position today to mitigate a pandemic than those 100 years ago.

“We’re so much better off now,” Coombs said. “Our health-care systems are much more developed. There were a lot of things that weren’t around, for example, penicillin wasn’t discovered until a few decades later so there was no treatment for anyone who had a bacterial infection. A lot of people who succumbed to the 1918 virus, they either died from cytokine storm or from some other infectious disease because their immunity was weakened.”

In studying the COVID-19 data, Coombs said it looks like the things we’re doing to help mitigate the pandemic, like social distancing and testing, are working.

“We might have a handle on this,” he said. “It’s a big ‘might’ because it’s still very early. It’s too early for people to go out and enjoy the sunshine and start doing the things we’re being told not to do. It’s tempting, but we can’t do it yet.”

Coombs is currently working with his colleagues at the National Microbiology Laboratory to potentially establish a research project to study COVID-19.

He said that scientists have known about coronaviruses for a long time and this knowledge will help researchers develop a COVID-19 vaccine.

“So I think the thing for people to realize is that this particular virus is relatively new but the group as a whole has been around and we’ve known about it for many decades,” Coombs said. “I am sure there will be a vaccine; the question is just how long it will take?”