Op-ed: Does it matter where a city council candidate lives?

The following is an op-ed written by Royce Koop, associate professor and head of the political studies department. It was originally published in the Winnipeg Free Press on Oct. 5, 2018.

A recent investigation on the Winnipeg civic election found that one in five Winnipeg city council candidates does not live in the ward they’re running to represent. Local journalists dug up the primary residences of all candidates and double-checked to see if they are in the wards. When candidates live outside their wards, the journalists cleverly measured the distance between their homes and the wards they are running in. Some candidates live within a hop, skip and jump of the wards they are contesting; others live further afield.

Fort Rouge-East Fort Garry council candidate Stephanie Meilleur got the ball rolling when she issued a news release announcing that one of her opponents, Winnipeg School Board chair Sherri Rollins, “…doesn’t even live in the ward!” However, in a classic case of throwing stones while in a glass primary residence, it was then revealed that Meilleur herself had only moved from a home in Warren to a West Broadway apartment seven months earlier. She splits her time between Warren and her Winnipeg apartment. Warren is lovely, but it is decidedly not in Fort Rouge-East Fort Garry.

The assumption throughout this reporting and subsequent discussion is that candidates for public office should live in the communities they seek to represent. There are good reasons why we would want this. For one thing, we want our representatives to have a personal stake in the decisions they make for the wards they represent. There are such immense differences in the needs and demands across Winnipeg’s wards that it necessarily feels wrong that an outsider would assume they understand those needs and demands.

We want our representatives to share in our experiences, as well as to bring those experiences to bear on the decisions they make. One way to increase the probability that this happens is to belong to the same community. This is especially true for the diverse, lower-income wards in central Winnipeg, where it might be difficult for someone from outside the ward to understand and work toward addressing the unique challenges that face these communities.

On the other hand, we can take this too far. Some candidates live just outside the wards they are running in. People may cross ward boundaries to take their kids to school, go shopping, visit community centres or visit friends and family.

The reason for this is that while boundary commissions try to preserve the integrity of communities when they draw ward boundaries, they can also create wards that do not reflect the lived experiences of all residents, especially those who live close to boundaries. Someone may be quite aware of the circumstances of a ward while living outside its boundaries.

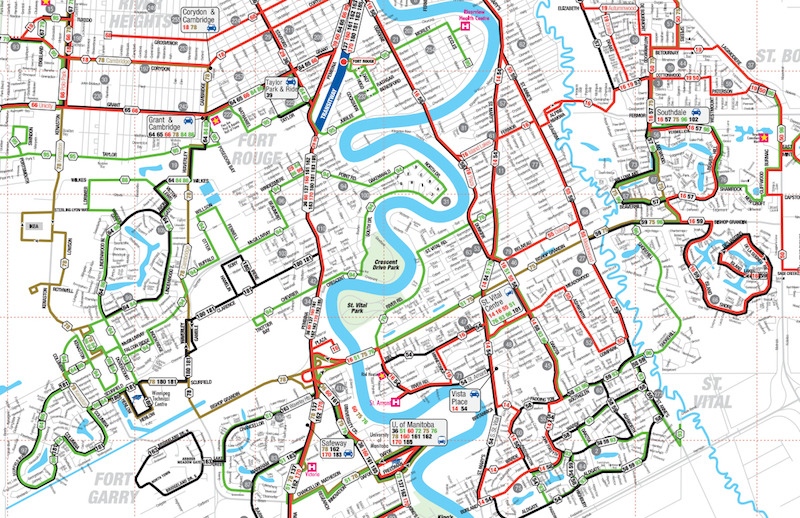

In fact, boundary commissions may create the opposite situation when they combine distinct communities into a single ward. My ward, St. Norbert–Seine River, includes River Park South, Fort Richmond and St. Norbert. These three neighbourhoods are distinct in their character and have different needs and concerns, and are separated by the Red River. It’s perfectly fair to ask whether a candidate from one of these neighbourhoods can truly understand the other neighbourhoods, yet this is not viewed with the same suspicion as candidates who live outside the wards they seek to represent.

Sometimes, candidates can use other local experiences to assure voters they’re familiar with the ward despite not living within its boundaries. Point Douglas candidate Vivian Santos, for example, lives outside the ward, but argues that her experience as executive assistant to departing councillor Mike Pagtakhan has given her insight into the important issues in the ward. It’s a convincing argument, especially because Santos was involved in dealing with constituency matters while in her position.

Further, the question of where candidates live ignores that representatives make choices about how they do their jobs and who they seek to represent. Some politicians are strongly focused on serving their constituents, while others are more focused on other matters, such as learning about and advocating for policy changes at city hall. Councillors make these choices and then have to justify them when they are up for re-election. Someone who lives outside a ward may nevertheless be a hard-working, conscientious constituency representative.

We should not assume that all councillors will be focused on their wards. In 2013, I surveyed councillors in Canadian cities about (among other things) their “focus of representation” — who they sought to represent as councillors. Of those councillors elected in wards, 70 per cent reported that they focused on a certain geographic area of the city, such as their ward. But 73 per cent of those councillors also responded that they hoped to represent the interests of their cities as a whole. And doing that does not require one to live in the ward in which they’re elected.