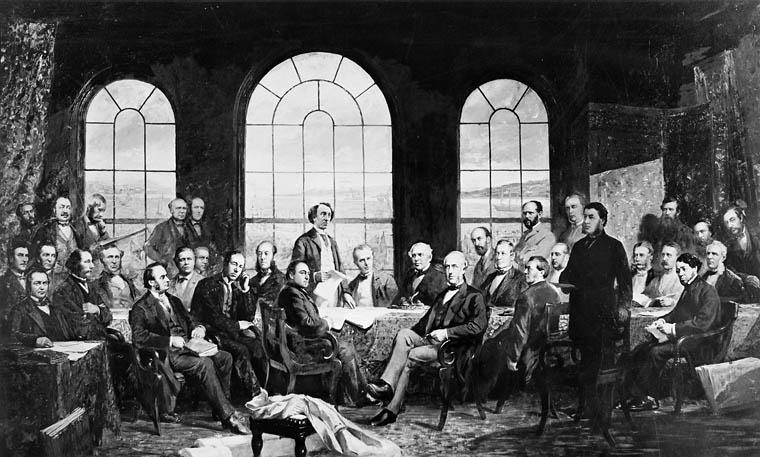

New parties find it difficult to get a foothold, professor Koop says. Consider the fact that Canada’s two largest parties — the Liberals and the Conservatives — are still variations of the same parties that were doing battle with each other in the 1800s // Image: "Fathers of Confederation" By Robert Harris

Op-ed: Bernier’s party likely won’t last

The following is an op-ed written by Royce Koop, an associate professor and head of the political studies department. It was originally published in the Winnipeg Free Press on Sept. 21, 2018.

Former Conservative party leadership contender and recently departed Conservative MP Maxime Bernier kept his promise to start a new right-of-centre party. So it was that the People’s Party of Canada (PPC) — espousing Bernier’s longtime views on federalism and taxes, as well as his more recent pronouncements on refugees and immigration — came into being last week.

Of all the remarkable things that have happened in Canadian politics recently, Bernier’s new party is perhaps the least consequential. Canadian history is littered with wreckage of small parties that started with a bang and ended shortly thereafter with a fizzle. This is in large part due to the system we use to conduct elections in Canada, which tends to favour big parties and punish small parties when it comes time to translate votes into seats.

Consider the fact that Canada’s two largest parties — the Liberals and the Conservatives — are still variations of the same parties that were doing battle with each other in the 1800s. Canada’s big parties have accomplished this remarkable feat by stomping all over “third party” challengers like Bernier. Of all the challenges to Liberal and Conservative dominance, the NDP is the only “third party” that has successfully broken into federal politics and remained a force.

Further, Bernier himself doesn’t provide much assurance that the PPC will be anything other than a flash in the pan. Building new parties is just plain hard work. Ask Preston Manning, who spent countless hours as leader of the nascent Reform Party of Canada, working to build the party organization before its breakthrough in the 1993 federal election. One must build party organizations from the ground up, and that includes shaking countless hands and delivering myriad speeches in legion-hall basements. The work is mundane and the payoff is always in doubt.

Bernier’s track record as a minister and MP contains amusing anecdotes which suggest that he perhaps lacks the tenacity and discipline to carry out this challenging task. For example: in 2008, Bernier forgot a confidential briefing document at his then-girlfriend’s apartment and, as a result, resigned as minister of foreign affairs. Bernier was also known for indulging in periodic catnaps during Conservative caucus meetings. As the story goes, Bernier’s surreptitious snoozing did not escape former prime minister Stephen Harper’s notice.

We all make mistakes, and God knows I’ve been tempted to give my eyes a rest during meetings here at the University of Manitoba. But I’m not the one proposing to build an entirely new party from scratch; Bernier is.

Still, certain people seem to want to give Bernier as many assists as possible. Maclean’s columnist Paul Wells, for example, speculated that Bernier’s voter base consisted of “the stupidest people on Twitter.” A CTV headline blared that Bernier favoured two-tiered health care, when Bernier had in fact explicitly stated that he opposed it. Such treatment by the media is a precious gift to insurgent politicians such as Bernier, who can point at apparent media bias and use it to attract support and financial contributions. Bernier did not miss the opportunity to do so.

I have every expectation that Bernier’s party will eventually fizzle. But Bernier could exercise a substantial influence on Canadian politics before his final departure. This could take place in several ways.

The most obvious is that Bernier may recreate what Canadian conservatives experienced in the 1990s and early 2000s, when right-of-centre voters split their support between the Reform party and the Progressive Conservative party, allowing the Liberal party to come up the middle and win four elections between 1993 and 2004. It was only when the right got its act together and merged into the Conservative party that the Liberals were eventually shown the door by the electorate.

Bernier may also influence both the tone and the content of Canadian politics. For example: he is a longtime critic of the supply management system that co-ordinates supply and demand of dairy and poultry products in Canada. Bernier claims it benefits wealthy producers and gouges consumers; by staking this position, he is challenging an all-party consensus in favour of supply management. This could make life difficult for Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer, a steadfast defender of the practice.

Bernier’s contrarian musings on diversity, refugees and immigration may also find an audience. The influx of irregular migrants across the Canada-U.S. border is potentially fertile policy ground for Bernier, as polls demonstrate that most Canadians see the influx as a crisis and disapprove of the federal government’s handling of it.

Scheer’s Conservatives have tried to give voice to public concern over irregular migrants while not going overboard, in order to avoid Liberal accusations of racism and fear-mongering. Bernier’s harsh rhetoric, in contrast, suggests that he is not much concerned about being accused of racism, and that he will exploit Canadians’ concerns on this issue more directly and effectively than the Conservatives have.

In so doing, Bernier will likely drag the Conservatives toward a tougher stance on migrants and change how we discuss this and other policy matters.