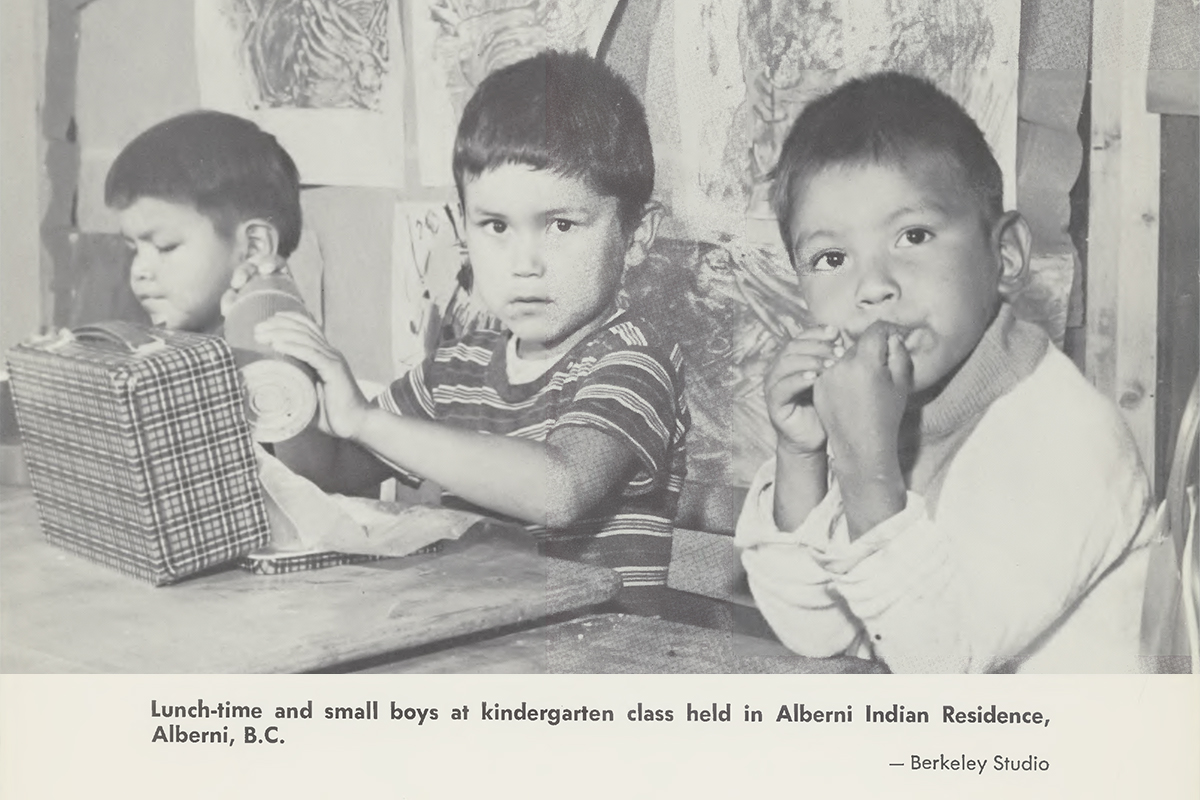

Most images in NCTR's archives only have the viewpoint of the colonists attached to them, as shown in this image. A new project will rectify this by having Survivors explain the context of the photos, providing their voice and perspective. // Image: NCTR

NCTR reimagines what its archives can be, and do

Will create a new international benchmark for making archives an agent of social change

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) is reimaging what its archives can be, and do, as it undertakes an ambitious project to restructure and decolonize its data, thanks to funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation’s Innovation Fund.

Raymond Frogner, head archives at NCTR, has received $2,411,773 for the national project team he will lead to rebuild the Centre’s digital architecture. The funding was announced on March 3, 2021, by the Honourable François-Philippe Champagne, Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry.

“The materials held within the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation are of primary importance to Canada’s future and I commend the NCTR on their efforts to reimagine how their archives can better serve all Canadians. Their project is a paradigm shift,” says Catherine Cook, vice-president (Indigenous) at UM. “The University of Manitoba is honoured to support the work of the NCTR.”

Currently, NCTR has access to roughly 5 million documents, siloed in various bureaucracies of government and church offices. The information was originally gathered by these institutions to meet their colonial needs and there was never a need or desire to connect the data points in meaningful ways. This new project will take on the herculean task of finding the narrative held within these documents. It will shift the focus away from the institutions and onto the individuals: future archive users, for instance, will be able to follow one student from school, to hospital, to school, and anywhere else they were shuttled about by settlers.

“Residential schools were a social engineering project of the federal government to basically erase Indigenous cultures from the Canadian landscape,” says Frogner. “In one sense, the records held by NCTR are very much the institutional, administrative records of the colonial operation of these residential schools…. But these records are more than the administration records of schools. They record of some of the most profoundly important events in a child’s life, and to bring Indigenous voices to them, is to decolonize them.”

This project will take four years to complete and it will maintain ongoing engagement with Indigenous communities as the projects evolve. It includes many team members from multiple institutions including the University of Manitoba, the First Nations Information Governance Centre, the University of British Columbia, the University of Winnipeg, and Ryerson University, and the National Film Board of Canada.

Another example of how the information will be decolonized involves photographs. Many teachers took photographs from within the Residential Schools and the information attached to them comes only from the teacher. This new project will allow Survivors to explain the context of these images from their perspective, greatly expanding on our understanding of what took place.

“There was a time when we Survivors did not speak of our experience at Residential School,” says Levinia Brown, NCTR Governing Circle member and Survivor. “Things are starting to change and we must honour those voices that were brave enough to share their pain. The work to be done through this grant is so important, not only because it preserves our words, but it will make them more available to all, including future generations. It is one crucial step we must take towards ensuring this history is not repeated.”

The open-source system to be developed will allow many other partners to access the data in meaningful ways.

Enter the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) in the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, which has a decades-long track record of using anonymized health data to spotlight community health issues. As the NCTR organizes records around individual students, a single virtual case file will be created. MCHP will be able to use these new files to look at the contemporary downstream health and welfare legacies of the childhood trauma that was experienced in schools. This will be the largest such study ever undertaken (the Netherlands did similar work on the effects of WWII, but not to the extent this project entails).

NCTR will also hold training sessions to empower communities to statistically analyze the data held in this new format so that they can glean their own insights, enabling them to work with source material directly rather than asking for an academic to assist.

“Communities, survivors and family members still have so many unanswered questions about both what happened in residential schools as well as the intergenerational legacies of the residential school system,” says Ian Mosby, project team member and assistant professor of history at Ryerson University. “Even now, though, the archives where they might find answers are almost totally inaccessible to ordinary people. By making the data and archival materials held by the NCTR accessible to communities and community-affiliated researchers, then, we’re enabling communities and individuals alike to take control of their own history in a way that’s simply impossible right now.”

The project will create a new international benchmark in cultural heritage policy, Indigenous rights management, Indigenous research and education methodologies, and Indigenous perspectives on IT development.

“It recognizes that, like human rights and public memory, archives are socially constructed,” says Frogner. “This recognition carries responsibility for archives to reposition themselves as agents of social change.”

NCTR is also preserving its vast stores of audio-visual recordings—over 7,000 items—with the help of the project collaborator, the National Film Board of Canada, so that all recordings made by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission will be available for generations.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.