Law and CATL host workshop on promoting classroom engagement

Law faculty and students share what works and what doesn’t to improve classroom engagement

Recognizing the universal need to improve the engagement of students in today’s classrooms, Assistant Professor Virginia Torrie recruited colleagues and students from Robson Hall Faculty of Law to discuss challenges and solutions at a recent workshop hosted by the Centre for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning (CATL). The February 13th noon-hour panel included Assistant Professors David Ireland and Shauna Labman, Associate Professor Amar Khoday, and law students Yassir Al-Naji, Caleigh Glawson, Madison Pearlman, and Zita de Sousa.

Each professor gave examples of techniques of classroom engagement that have worked for them, while students shared experiences of strategies that have caught their attention in what would otherwise be extremely dry – but mandatory or critical material that they need to know for their degree program.

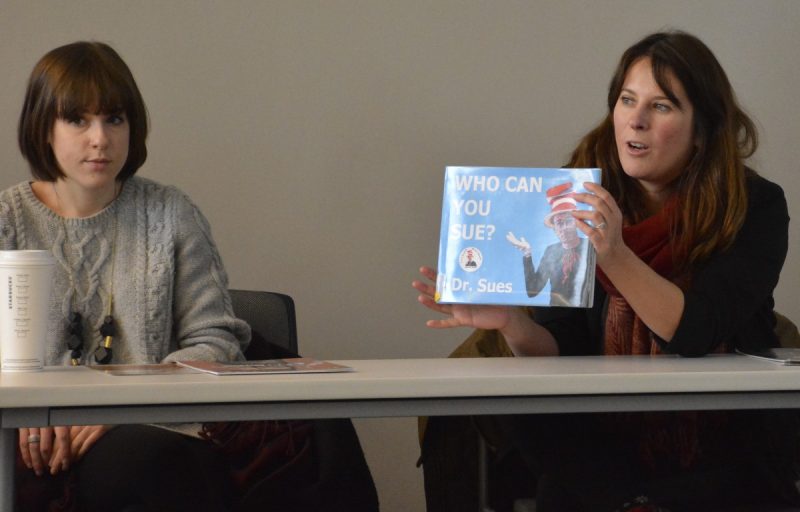

Student Madison Pearlman (3L) looks on as Assistant Professor Shauna Labman shows off a creative class assignment that helped students retain otherwise dry information.

No Investment, No Return

Labman found having her students write either a critical or creative commentary on a case in her Torts class (a mandatory course for all law students), resulted in excellent retention of lessons. One creative assignment example was a Dr. Seuss-style book two of her students did for their assignment. Although having to mark all the 30%-valued assignments was time consuming, Labman said, “Those students will never forget the lessons they learned.”

The difference between student engagement and success in class, she said, is where students “are not engaged but still doing well”. Getting students to do both involves more grading for the teacher and more assignments for the students, but she found that, with shorter or online assignments including use of UM Learn discussion boards, students were getting and staying engaged with discussion continuing outside of class.

Reality Check

Pearlman (3L), who took Immigration Law with Labman, said having assignments throughout the term rather than basing grades on a 100% final exam engages students more during class time. Having guest speakers and going to actual Immigration and Refugee Board hearings outside the classroom, she said, helped students to see the practical application of what they learned in class.

Gawson said having a professor like Ireland is great because he has actually practiced law. She said it was very helpful to hear his personal experiences from which students could draw real- life, practical examples that helped them to understand the law and how to use it.

Khoday recalled that as a law student, he also most enjoyed professors who applied a lesson to an actual example. “Having an opportunity for students to talk through a problem is a good way,” to get the discussion going, he said, adding he now has students write their thoughts down and upload them to UM Learn to keep the conversation focused. “There’s more accountability to have them generate a written document,” he said, adding, “It helps solidify material in their heads rather than just lecturing [at them].”

Lively Discussion

When he first started teaching the mandatory Evidence course, Ireland said, he tried to develop students’ communication skills by starting with a low-pressure engagement exercise like putting quotes on the screen and having the students read them out loud. Incorporating small group exercises engaged students more with each other and with the material, he added.

Al-Naji found getting involved in classroom discussion to be effective, for example, getting students to think about why a particular criminal code provision is in place or how can it be made more effective. “You may not be interested in criminal law,” he said, “but if you invite people to discuss it in a more policy way than an academic way, you get more people engaged. Invite opposing views is good.” An example of the latter, he said, was in his Bankruptcy class where Professor Torrie would invite an opposing view and then step back while the students engaged in discussion.

Knowing That You Know Nothing is Just Fine

De Sousa observed that in law school, “you don’t know what you don’t know,” adding that Professor Torrie made her interested in classes she was not originally interested in by sheer teaching technique. Torrie regularly uses the educational software, Socrative, she said, with which students could anonymously answer questions and then see if they understood what they were just taught. As De Sousa explained, it was, “a good tool to help point out weaknesses or build confidence that you’re not off.” Additionally, she said she found it helpful when Torrie played video clips of news articles to show how laws were working in the world around them.

Speaking from her own experience, Torrie said she hadn’t realized how hesitant students are to raise their hands and ask questions. Rather, she found they were more comfortable sharing in class after they had had a chance to discuss material with fellow students in small groups.

Possibly a characteristic of law students in particular, Al-Naji observed that often when professors ask questions of the class, no one wants to give an obvious answer, but at the same time, no one wants to be completely wrong. Instructors need to find a “sweet spot” where a question is not insultingly easy, and not so hard that no one will take the risk of answering incorrectly. Another reason for non engagement, he said, is simply because students are asleep. To get everyone’s attention, just say the magic word: “exam” and everyone will perk up, he advised. Even, “This is not on your exam,” will awaken sleepers, or changing up the class like having a group assignment or a break can relieve the boredom.

De Sousa observed that an obstacle to classroom engagement is material that is simultaneously important but dense and boring. The problem is that after a professor has talked for 3 hours and then asks if anyone has any questions, no one will be able to engage. De Sousa recommends having short breaks, or if everyone looks like they’re in pain, then to stop and check in with students rather than inviting questions at the very end. “No one wants to be that student who holds up the class with a question with five minutes left in a three-hour class,” she said.

Torrie said she has noticed how everyone suddenly becomes more engaged in their laptops whenever she asks a question. But rather than take it away, she said, “If technology is in the classroom, let’s use it for something,” citing her use of video clips and slides as being effective.

Torrie said she has had to work hard to make her drier courses like Bankruptcy Law interesting. It would seem that her hard work has paid off, with students like De Sousa signing up for the course simply because she liked Torrie’s teaching style, even though her interests lie in Criminal Law.

Obstacles to Classroom Engagement

- Dry but mandatory material;

- Long lecture without breaks;

- Timing and challenge-level of engagement-seeking questions;

- 100% exams = no reason to attend or engage in class;

- Inappropriate use of power point slides;

- Online shopping (!)

The Unfortunate Case of Online Shopping

Ireland echoed that major obstacles to classroom engagement include boredom. The unfortunate fact is that mandatory classes are not for everyone. “Computers in classrooms are a big distraction with social media and online shopping,” he said explaining that he has entered classrooms from the back and been incredulous to see that everyone is engaged in purchasing something. “I don’t get it!” he said.

To combat screen time, he tries to break up classes with small groups or some kind of face to face engagement. Most people need to take notes on their computers but Ireland has found taking students off-screen to be effective. For example, he will try to use students as actors in a legal scenario to illustrate the law. It helps to look at faces when thinking about legal situations, he said, and it seems to have increased the level of engagement.

This year, Torrie is teaching a smaller seminar and does not have any computers in the room. With this paper-based course, students tend to take hand written notes or no notes at all. De Sousa, who is taking that seminar, noted that students listen actively in that setting, “because there is nothing else to do. Making eye contact makes a huge difference,” adding that was how she got more engaged.

Effective Classroom Engagement Techniques

- Engaging in lively classroom discussion;

- Creative assignments;

- Small group discussion;

- Invite opposing views

- Splitting long classes with breaks;

- Relating material to real-life examples;

- Attending actual hearings outside classrooms;

- Inviting guest speakers;

- Using technology to advantage (i.e. UM Learn, Socrative);

- Communicating purpose of readings and assignments;

- Communicating class expectations at outset;

- Strategic use of power points;

- Out-of-class access to instructors.

Learn with Purpose

Glawson noted that it is not effective when a professor assigns 10 cases to read without explaining what they are for, leaving the student to discover after the fact that they are reading a history lesson of the case law. “If I don’t know the context going into the reading,” she said, “it’s frustrating by the time you get to the end. Having purposeful readings is better rather than not knowing the purpose of the reading at the outset.”

Pearlman noted that it is critical for professors to acknowledge that not everyone is interested in the mandatory courses and set expectations at the start of the school year. Students appreciated a particular professor who said on the first day of a mandatory class, that, “I know you guys maybe don’t want to be here today,” she said. “Demonstrating that you’re aware of the realities of the class is appreciated by students,” Pearlman said.

Khoday said subject matter plays a role in classroom engagement. While criminal law is not hard to engage students, administrative law is far more dry. For his part, he shows video clips and then has students identify legal issues in them. Allowing students to participate online also helps, and Khoday found that when he invited online comments for marks, the amount of comments submitted far exceeding the required participation.

Pros and Cons of Power Points

Having power points made available before class is very helpful, De Sousa said, since it means students don’t have to split their focus between what’s on-screen and what the professor is saying. Without advance power points, students are frantically taking notes and not paying attention to the lecture. “Then you get garbage notes and garbage listening,” she said.

Al-Naji agreed that slides posted online were a good idea, but a down side to that is that once students have them, the professor has lost 75% of the class. To combat the risk of no one showing up or paying attention in class, he recalled one professor who would post slides online but leave words missing from them so students were forced to pay attention in class. Finding a middle ground with providing notes versus not providing notes is important. “No one wants to type out the whole screen,” he said, “but at same time if the whole thing is available online, they won’t be paying attention: they are shopping.”

One way to avoid the frantic scribbling of notes and unresponsiveness to questions, Al-Naji suggested, was to ask questions with a blank slide showing to force people to look away from the slide or their computers and pay attention to the instructor.

Lastly, De Sousa noted, “Don’t read the text book to me. I’ve already done that.”

Last Thoughts

Al-Naji summarised the students’ sentiments saying, “when you take a really well-taught course from a professor who is clearly passionate about the material, it makes you want to take [it]. I think students in law school will take a class based more on who’s teaching it rather than the subject.”