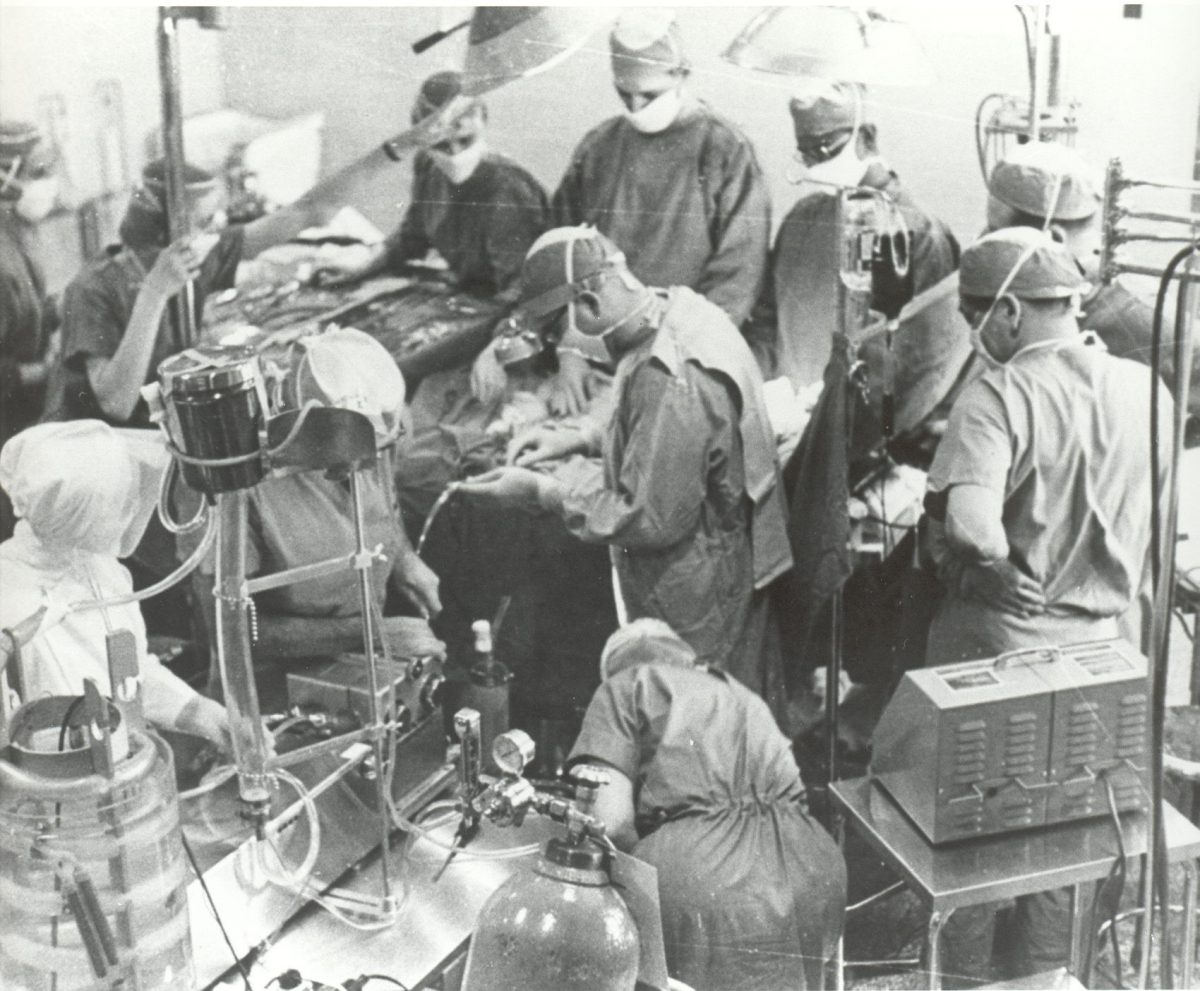

THE PHOTO ON THE BOOK'S COVER DEPICTS DR. MORLEY COHEN PERFORMING MANITOBA’S FIRST OPEN-HEART SURGERY AT ST. BONIFACE HOSPITAL IN 1959.

New book celebrates Manitoba’s Jewish doctors

The stories of generations of Jewish physicians who have influenced the course of health care, medical research and medical education in Manitoba are chronicled in a new book.

Healing Lives: A Century of Manitoba Jewish Physicians has a free, public launch on Nov. 3 at 2 p.m. at the Berney Theatre on the Asper Jewish Community Campus. It also has a launch on Dec. 8 at 2 p.m. at McNally Robinson Booksellers, Grant Park.

Published by the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada, the book is the product of several years of information-gathering and fundraising by a committee from the Jewish community. It includes a foreword by distinguished Jewish Canadian historian Irving Abella.

“In the first half of the 20th century, and even later, Jewish physicians had to overcome prejudice,” says Dr. Jo Swartz, an anesthetist and U of M faculty member who was active on the committee and whose father, Dr. Mel Swartz, was a well-known urologist.

“They were so dedicated,” Swartz says. “They persisted and they excelled. They treated their patients with compassion. And many of them explored the edges of science and medicine.”

With the goal of documenting the more than 400 Jewish physicians who have practised in Manitoba since 1881, the book committee received research assistance from the Jewish Heritage Centre, and from University of Manitoba medical archivist Jordan Bass.

A U of M website was established so that anyone with information or archival material could submit it. Eva Wiseman, an accomplished Winnipeg author, was hired to conduct further research and write the history.

Dr. Arnold Naimark, who was named the first Jewish dean of medicine at the U of M in 1971 and went on to become university president, also served on the book committee. It was important, Naimark says, that the publication be more than a who’s who.

“It’s not only about who these physicians were, but what they contributed, and how that played out in a social, political and economic context,” Naimark says.

The book recounts how, from the 1880s through at least the first half of the 20th century, Manitoba Jews faced overt discrimination. They were excluded from many careers, but medicine was open to them. Although many encountered obstacles in obtaining internships and hospital appointments, practising medicine fit with the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, or “repairing the world.”

The book recounts how, from the 1880s through at least the first half of the 20th century, Manitoba Jews faced overt discrimination. They were excluded from many careers, but medicine was open to them. Although many encountered obstacles in obtaining internships and hospital appointments, practising medicine fit with the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, or “repairing the world.”

By the 1920s, Jews were well represented as students at the U of M medical college. Then, in the early 1930s under a bigoted dean of medicine, the college introduced a covert quota system to exclude many Jewish and other minority students.

In 1943-44, a U of M mathematics lecturer named Shlomo Mitchell led a small group of Jewish students in gathering evidence of the quota system. Mitchell’s whistle-blowing cost him his job. But he and his group succeeded in ending the quota by exposing it to the Manitoba government. As Abella writes, “It was the opening skirmish in the fight against anti-Semitism in Canada in the 1940s.”

Today, as Wiseman notes, the once-discriminatory college is named the Max Rady College of Medicine in honour of a Jewish physician. Rady graduated from the U of M in 1921 and was known – like many Jewish doctors of the pre-medicare era – for treating patients regardless of their ability to pay.

The social conscience of the Jewish medical community is a strong theme in Healing Lives, from the founding of the free Mount Carmel Clinic – which some dreamed would become a Jewish hospital – to a groundbreaking health-care scheme introduced in the late 1940s.

Under this plan, Winnipeg garment factory owners paid into a health fund. Garment workers also contributed a small percentage of their wages. The Mall Medical Clinic, which had been founded in a socialist spirit by predominantly Jewish doctors, was then paid by the fund to provide health services to the workers and their families.

It was, Wiseman writes, “the first union-industry prepaid medical plan in Canada, and perhaps in all of North America.”

Healing Lives profiles trailblazers such as Dr. Jack Hildes, the hero of Winnipeg’s 1953 polio epidemic and founder of the U of M’s Northern Medical Unit; Dr. Lyonel Israels, a hematologist who was the patriarch of cancer care in Manitoba; and Dr. Mindel Cherniack Sheps, one of the few Jewish women admitted to the medical school under the quota. Sheps, a public health expert, moved to Saskatchewan to advise the government on introducing medicare.

Other notable figures include, to name only a few, palliative care innovator Dr. Harvey Max Chochinov, renowned geneticist Dr. Cheryl Rockman-Greenberg, inflammatory bowel disease specialist Dr. Charles Bernstein and children’s health champion Dr. Dorothy (Osovsky) Hollenberg, a member by marriage of Winnipeg’s Hollenberg medical dynasty.

“Jewish physicians have taken their place in every aspect of the medical profession,” says Naimark.