James Kinoshita (BArch/56) : The Modest Man Behind Modernist Icons

Icons often represent a city. The Statue of Liberty for New York. The Eiffel Tower for Paris. The Opera House for Sydney. These beacons are more than art or architecture: they represent the collective aspirations of a people, a place, a slice of time when everything seemed possible.

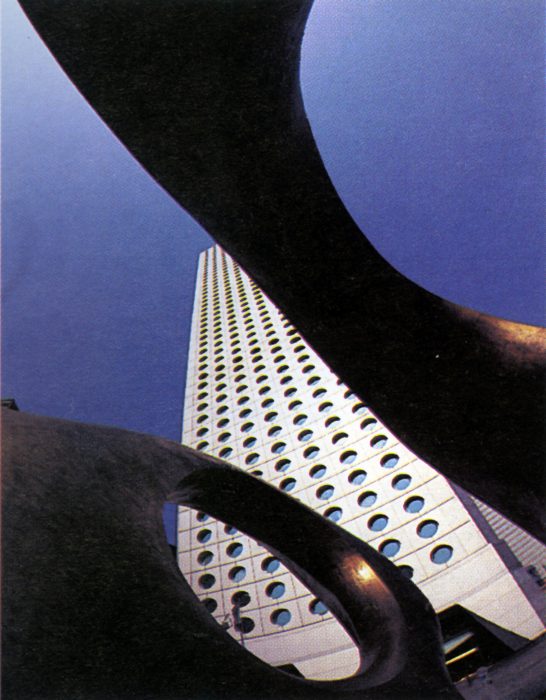

In Hong Kong, there are many icons jockeying for second place: Foster’s HSBC Building, Pei’s Bank of China Building and, more recently, Pelli’s 2IFC and KPF’s ICC. Despite the latter two’s combined height of 915 metres, the city’s top dog remains Jardine House (originally Connaught Centre). As HKU architecture professor Eunice Seng unequivocally states: “Jardine House has been an icon for Hong Kong from day one.”

50 years young

JH50 Public Talk (HKLand).

On July 15, 2023, Seng was part of a panel at Jardine House: An Icon That Shaped a City. Held in Jardine House’s Basehall 2.0, the talk kicked off a series of events celebrating the building’s 50th anniversary. After the talk, a Q&A session open to the standing-room-only crowd unwittingly bullied James Kinoshita. The former partner with P&T (originally Palmer & Turner) and design architect of Jardine House was in the front row. Someone asked about the peeling tiles originally cladding the building’s façade, addressing Kinoshita personally for an explanation why he would endanger the safety of passersby. Moderator Anderson Lee diplomatically intervened—after all, Kinoshita was a guest of developer Hongkong Land. The 90-year-old should not be publicly hanged for an alleged design error that occurred more than half a century ago.

The topic of those pesky tiles resurfaced in early December at Kinoshita’s home in the Sai Kung countryside. At a bend in a leafy lane off Hiram’s Highway, a red gate opens up to a two-story house facing a sheltered bay designed by the Canadian-Japanese architect. “The original façade was intended to be aluminum,” he recalls. “Tiles were an alternate, but its tender came in much lower. HKLand just paid the highest ever in the city for a plot to build Jardine House. We understood why they went for the cheaper option. A few years later, when the tiles started falling off, we replaced them with aluminum sheets.” He smiled: “By then, they could well afford them!”

Going up

Jardine House (P&T).

For Kinoshita, architecture is not about concept. Rather, it is finding a solution for a problem in a logical, economical way. In the case of Jardine House, it was how to build the city’s tallest building in 1973 as quickly as possible, in order to make money as soon as possible from tenants in the grade A office tower. As usual, commerce rules in Hong Kong—and the city is never ashamed to admit it. The icing on the cake is that Jardine House also happens to be iconic in no small part because of its circular windows.

“The best solution was caissons, but that was rejected in favour of piles,” recalls Kinoshita. “The building had to be as light for the least amount of issues when it settles on the newly reclaimed land. We came up with the idea of a light shell—like a lobster shell—for the façade. And of course we needed windows, for additional lightness in the concrete. One weekend when I was working on the elevations at home, my wife saw them. She criticized that they were boring, suggesting round windows instead. Our HKLand client Henry Keswick agreed.”

Rationality may appear inevitable when it is a perfect storm of inspiration, site, client, budget, user and luck. Kinoshita’s modernist approach combining concrete, glass and steel at a time when Central was awash in Victorian architecture may be partly attributed to the teachings of John Russell at The University of Manitoba (UM). Russell himself trained at the Illinois Institute of Technology—at the time it was Mies-led—and whose style is exemplified by the building that bears his name at the faculty where he was Dean for decades.

Winnipeg warmth

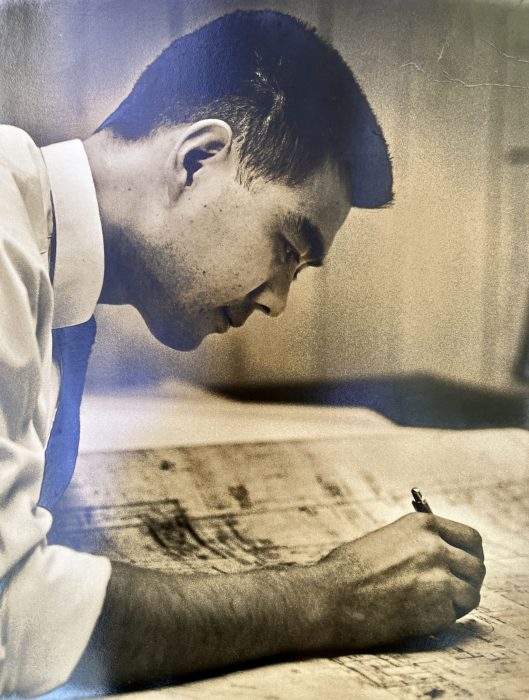

James Kinoshita in 1962 (courtesy of James Kinoshita).

“Dean Russell was a real gentleman,” recalls Kinoshita, noting that the late professor taught him colour and art history. During those years, the architecture studio was housed in a string of huts—think large tents—along the Red River. For the Vancouver native, keeping his fingers nimble enough to wield a pencil during cold Prairie winters yields bittersweet memories. Returning to the welcome warmth of Tache Hall where he resided for five years was much appreciated at the end of every day. And all his hard work paid off. When Kinoshita graduated in 1956, he was a gold medallist with scholarships to both Harvard and MIT. “I chose MIT because Dean Russell and professor Roy Sellors—who taught building construction—both highly recommended it, being MIT grads themselves.”

It was at UM where Kinoshita met interior design student and Hong Kong native Lana Cheung, herself also a gold medallist. After completing graduate studies and a stint of work in the States, he flew to Hong Kong to make Cheung his bride in 1961. The same year, he began working for established local practice P&T on the Hilton Hotel and remained with the firm until retiring in 1988. Though demolished in 1996 to make way for Cheung Kong Centre, the Hilton is fondly remembered as an American challenger to Mandarin Oriental (originally The Mandarin) further down the hill.

Fate has a funny way of coming full circle. When Jardine Matheson (parent company of HKLand) expanded its hotel portfolio, it looked to partner with a legend—and found it in The Oriental in Bangkok. Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group was born in 1985 with The Mandarin and The Oriental as its flagship properties. When The Oriental increased guestroom count, P&T was retained to design its River Wing. The site dictated a tower with minimal Chao Phraya River frontage. Kinoshita angled all the glazing 45 degrees, giving every room a view of Bangkok’s mighty waterway when opened in 1976. Arguably the best hotel in the world and the Thai capital’s de facto living room, the hotel can thank P&T for a modern addition that allowed more travellers to experience its grace.

Creating a landmark

The Landmark Atrium (P&T).

Kinoshita was practicing at time when Asia was racing to catch up with the west. When HKLand wanted to redevelop Central, it played the long game and swapped a number of buildings to secure adjacent plots of land where it could build bigger and higher. The Landmark complex is the core of its commercial property portfolio, with P&T responsible for its twin 44-story office towers and a retail atrium connecting them.

Inspired by the piazzas of Italy, Kinoshita envisioned the atrium as a hub where people gathered for spontaneous chats or large events. He toured major American shopping malls to research what worked. Completed in phases between 1975 and 1983, The Landmark included a rooftop array of glass pyramids to allow natural light into the climate controlled three-story arcade. A sound-propelled vibrating sculpture by artist Wen-ying Tsai originally stood centre stage, but was eliminated when adjacent shop tenants complained about people incessantly clapping to activate it. Today, the fountain that replaced it is where everyone arranges to meet in Central. And The Landmark is very much Hong Kong’s living room for the well-heeled.

When asked if he considered the longevity and importance of what he was designing, Kinoshita says it was his job. That is not to say he does not love his work or great architecture. He clearly does. He simply hails from a generation that considers architecture as a job to support his family, not to be dissected, analyzed, rehashed and rehash tagged. And certainly not for its creator to headline TED Talks with posed portrait plastered on webzines. In the end, architecture should first be about the people it services rather than the architect himself. What makes Kinoshita worth the ink is the number of impactful projects in his 29 years with P&T at a time when Hong Kong was searching for an identity pre-97 handover. His work gave—and continues to give—the city a look, a mood, a sense of belonging. A raison d’etre. And, naturally, a cool dystopian movie backdrop.

Coming home

Siu Wo Court courtyard (P&T).

Case in point is Siu Wo Court, a public housing project in the Hong Kong New Territories suburb of Fotan. The government-subsidized scheme intended for lower income families to afford to purchase their own home at well below market rates. With a trio of three 36-story towers clustered about their own courtyards and completed in1980, there were 3,501 units for sale. Tens of thousands homeowners spanning two generations have resided at Siu Wo Court, living in high-rise blocks where many newcomers to the city planted roots and forged community bonds. Kinoshita’s design is supported by open courtyards and sunlight swollen lift lobbies with the circle as a recurring design motif throughout.

Over afternoon tea, Kinoshita reflects on the challenges that budding architects face today. “They need to do it because they enjoy the work,” he muses. “If it’s money or fame they are seeking, they may be very disappointed.” When pressed that his words are wise advice coming from the Hong Kong’s very own Pei, he smiles and looks out to sea.