Canada the New Homeland. Poster reproduced in "Canada West". // Image: Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 2958967)

Globe and Mail: How the death of Colten Boushie allowed a myth to be told in court

The following is a column written by Gina Starblanket, assistant professor with cross-appointments in the U of M’s Native Studies Department and the Women’s and Gender Studies program. She is Cree/Saulteaux and a member of the Star Blanket Cree Nation in Treaty 4 territory in Saskatchewan. Her co-author is Dallas Hunt, a lecturer in the U of M’s Native Studies Department. He is Cree and a member of Wapisewsipi (Swan River First Nation) in Treaty 8 territory in Northern Alberta. This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail on Feb. 13, 2018.

A castle in who’s kingdom

During his opening statements in the trial of Gerald Stanley, the Saskatchewan farmer who on [Feb. 9] was found not guilty in the murder of young Cree man Colten Boushie, defence lawyer Scott Spencer told the jury that, “For farm people, your yard is your castle. That’s part of the story here.” In the days that followed, some of the media coverage of the trial focused on the question of whether the notion of “defending one’s castle” justifies the use of force resulting in injury or death to those who enter spaces they are seen as not belonging to.

Yet missing from the coverage, and absent in much of the discussion surrounding the trial, are the ways in which this sequence of events is intimately tied to the histories and present-day settlement of the country currently called Canada.

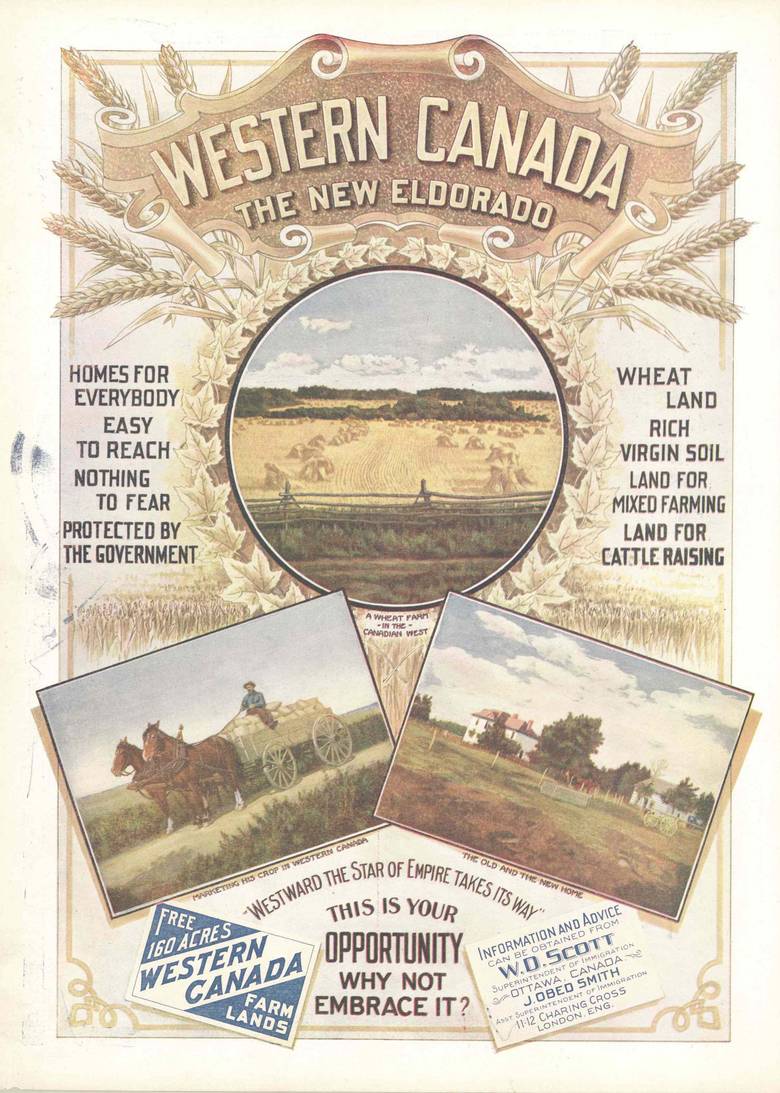

As the story goes, the Crown negotiated peaceful and consensual treaties with Indigenous populations that allowed for the settlement of the Prairies in exchange for the promise of civilization and protection. Early immigration posters and handbooks described the region as a vast, unoccupied, fertile hinterland, with little, if any, mention of Indigenous peoples. Colonial settlements offered newcomers property, independence, industry and, most of all, opportunities for wealth and bounty that would vastly exceed those available in their countries of origin.

The imagery shown on these advertisements and immigration materials, geared toward encouraging rapid settlement in the Prairies, idealized a patriarchal, nuclear family and an agrarian lifestyle. The central figure was typically an able-bodied, middle-aged farmer, often with his beautiful young wife by his side and a child cradled in his arms. In the background was often an image of the wide-open Prairies upon which his property – his “castle” – lies.

These images help illustrate the intent behind the process of settler colonialism – not just its foundations, but the norms, values, expectations and aspirations that were held by individual settlers and inherited by many descendants. These images are noteworthy for the highly gendered, whitewashed, capitalist ideologies that they signify; namely, normative ideas of the family, home and domestic life.

They simultaneously appeal to, and uphold, the institution of masculinity: the ability to build a home, provide for and protect one’s family, and – most importantly – to exercise control over one’s private domain. This domain purportedly exists and is bound within a lawless land, with the farmer serving as king of this realm – and of his castle – whose responsibility it then becomes to protect against intrusions or disruptions of this narrative.

However, as with any story, this isn’t the only version. For even more telling than the stories that are represented in these images are the stories that aren’t shown at all. When we show these depictions in our classrooms, the immediate response from most of our students, when asked to reflect upon what is absent from these images, is the clear erasure of Indigenous presence. Colonial settlement narratives either absented Indigenous peoples entirely from their portrayals of Prairie life, or when they did appear, they were described as occupying a role that would not interfere with the agrarian settler lifestyle.

These images help to historicize the contemporary hyper-racialization and gendering of space in the Prairies. For it is not only Indigenous peoples’ physical bodies that are under assault in processes of colonial dispossession, but also our long-standing relationships to our ancestral lands. These images speak not only to the absence of Indigenous bodies from colonial spaces as a past phenomenon, but also to the ongoing violence and dispossession that is necessary to create, maintain and “secure” these idealized colonial settlements. After all, Indigenous removal and erasure aren’t just historical events; rather, our attempted eradication has to be actively carried out in perpetuity.

The dispossession and assault on continuing Indigenous presence has assumed a variety of forms over the years: from one-sided and false interpretations of treaties as land transactions, to forced removal and imprisonment on reserves, to the residential-school system, to the legislated removal of Indigenous identity through policies of enfranchisement, among many other things. The drive to eliminate Indigenous peoples is – quite literally – part of the foundational structure of this country. Of course, this eliminatory logic targets Indigenous bodies not just because of their physical presence, but because of their difference.

Under the Indian Act, for many years it was illegal for Indigenous peoples to even protest the conditions of our oppression, as raising money to fund court cases in the interest of protecting our basic human rights rendered us as criminals in our own homelands. In other words, when we attempted to address colonial intrusions, our efforts were criminalized. As was our very presence outside of reserve lands.

For its part, Canada sought to achieve this by presenting Indigenous lands as lawless spaces absent legal order and continually crafting and revising the judicial narratives that gave settler legality to these spaces, as critics such as Anishinaabescholar Heidi Stark have argued. The colonial formation of Canada’s legal and political institutions is also reflected in the enduring relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in these geographies. Thus, we should not lose sight of the ongoing link between trading forts and individual farmers’ “castles” and the fraught histories of these spaces on the Prairies. Indeed, after the North-West Rebellion in the area of Fort Battleford in 1885, and the subsequent hanging of those who took part, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald remarked in a letter to Indian Commissioner Edgar Dewdney that “the executions … ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs.”

Given this history, it should come as no surprise, then, that Gerald Stanley’s defence lawyer Scott Spencer argued that for farmers, “your yard is your castle.”

But what if we invert the intruder narrative?

What should not be lost here is how castles (and now farms) have served as sites of capitalist accumulation and protectionism, as romanticized spaces wherein white knights protect against incursion from hostile outside forces. Like a modern-day Lancelot, the castle narrative draws on the need for a farmer not only to protect his kingdom, but also the need to save his “maiden” from the inevitable threat posed by racialized outsiders. (It should be noted that Mr. Stanley claimed one of the reasons he approached the SUV in which Mr. Boushie was sitting was because “I thought the car had run over my wife.”)

Indeed, media coverage of this trial – and discussion in the days after the verdict – was rife with outspoken farmers in the Saskatchewan farming community advocating for violence, having viewed themselves historically, and in the present day, as heroic frontiersmen taming the wild and cultivating their little outposts of empire. But here we ask the following question: How is it that the death of a young Cree man becomes recast as the story of a knight protecting his castle? What of the untold stories of those whose lives and homelands are continually subjugated in order for this imagery of “the castle” to be sustained? Castles evoke mental portraits of fortresses besieged, of hordes of enemies attempting to crash the gates of the wealthy, aristocratic and armed gentry defending themselves against the blood-thirsty intruders outside their walls and beyond their moats. These, no doubt, are the images and representations that the castle narrative intends to cultivate in the minds of those sympathetic to or willing to entertain the idea that the use of deadly force is justified to defend colonial settlements.

But what if we invert the intruder narrative? What if we bear in mind that the continuity of settler presence on Indigenous lands is itself premised on intrusion, a constant structure of intrusion dependent upon Indigenous disappearance? How can we reconcile the inhospitable notion of “intrusion” that then rationalizes settler violence with the nearly inconceivable acts of generosity that Indigenous peoples have extended and continue to extend in agreeing to share the land through treaty? Viewed from this perspective, the settler imagery of a constant threat of Indigenous violence appears as a perverse reversal of the actual colonial reality: that Indigenous existence itself is understood by settlers as a threat that always already rationalizes the use of violence. The outpouring of extreme racism following the jury’s decision is only further evidence of the ways in which the legal entrenchment of the “castle” narrative functions to enhance settler entitlement to enact violence to protect their claims to land and property.

Erica Violet Lee, an Indigenous community organizer from Saskatchewan, spoke out about the violence perpetrated against Colten Boushie and what she saw during the pretrial for Gerald Stanley. She remarked that regardless of the story the defence provided, “The reality is that Gerald Stanley left that farm alive, and Colten Boushiedid not.” The journalist who interviewed her provided the following description of Lee’s presence at the pretrial: “[Lee] sat on a small uncomfortable chair in the chamber, the size and structure of which made it difficult for people in the courtroom to physically comfort one another. The court proceeding took place under a looming portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, whose royal officers were positioned outside the courtroom, monitoring the crowd outside who had come to grieve.” The castle and its attendant imagery is alive and well even in the spaces that absolved Gerald Stanley of being responsible for the death of Mr. Boushie, in a site that was supposed to deliver justice. Yet this narrative is intimately linked to Indigenous peoples’ common stories as well – that is, the historical and contemporary forms of sexism, racism, violence and oppression upon which colonial castles are built.

Read More

Law Professors prove a valuable resource for information on juries following Stanley verdict

U of M President David Barnard issues a statement on the trial.