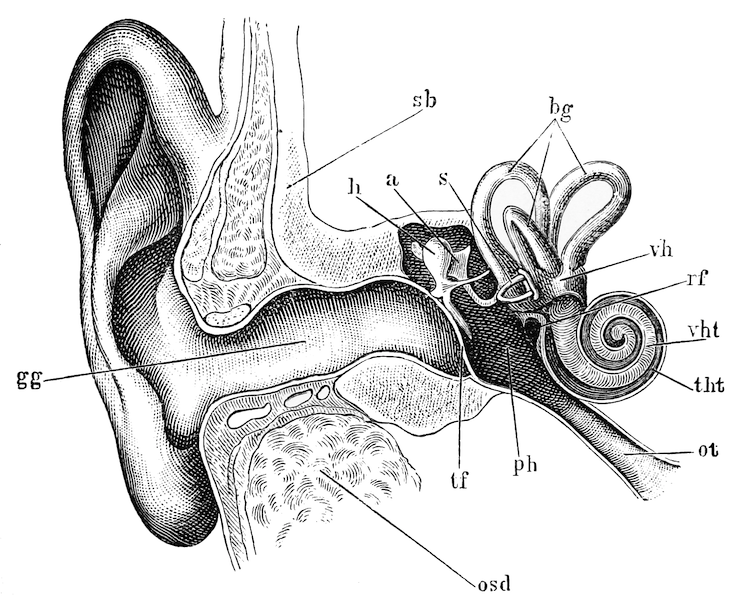

dig! The art of hearing

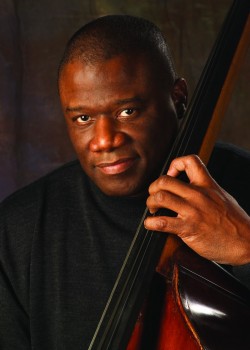

The following was written by Desautels Faculty of Music professor Steve Kirby for dig! magazine. It was originally published in the magazine’s September/October 2015 issue.

I think hearing is a most difficult art form, and that’s largely because listening is a most difficult task. Ironically both functions are among the most essential aspects of social interaction.

The toughest part about listening for me is hearing an external voice through a cacophony of internal voices. Whether I’m in a classroom or a board room or a doctor’s office or just sitting on the sofa chatting with a friend, listening to what another person is saying is challenged by my preconceptions of what they will say, whispering hopes of what I want them to say, running internal reactionary dialogues about what they just said, and nagging insecurities about what I hope they won’t say—all this punctuated by what my ego has decided I deserve to hear them say. Some of the voices are extremely loud and raucous, and some appear as constant background noise as though spoken by the wind. It goes on and on.

I realize that it’s risky to publicly introduce the little voices in my head, but judging by my daily social interactions, I suspect that I am part of the vast majority in this world.

Here’s an example: a student presents a question to me, and during my answer I notice all the social markers of being in a real conversation—the head nods, the uh-huhs, etc—but I can tell I’m merely speaking to the answering machine. I see their eyes moving about as though they’re in an altogether different conversation. By the end of what I have to say, I get a head nod, and they draw conclusions from their own inner dialogue that are entirely disconnected from what I said. (These are golden opportunities, mind you, to read their projections, but that’s another topic.) So I then rearticulate—and they reassert. Sometimes after several attempts, I concede to their conclusions and retreat to take up the conversation at a later date when their experiences draw them a little closer to valuing what I have to say about the subject.

Or vice versa. I’m not exempt from guilt in these situations.

These communication blocks happen on the bandstand too. When a drummer stares deep into the drums to play with a band, it’s like watching a person turning inward during a conversation. They begin to disconnect from the beat first, then from the dynamics, then finally the form. All you hear next is drum,drum, Drum, DRUM!!! The last thing I want to be aware of is a person’s instrument. I just want to be aware of their music.

Success in jazz gets down to how well you listen and how well you react to what you hear. I find that I’m the most successful when everything that I do is informed by everything that I hear. None of us can function at our best when all we hear is a cadre of internal voices. I’m learning to shut them off.

We are all learning to listen together at The Hang. Come and join us every Wednesday evening at The Orbit Room as we learn to listen to—and hear—each other more effectively as a community.