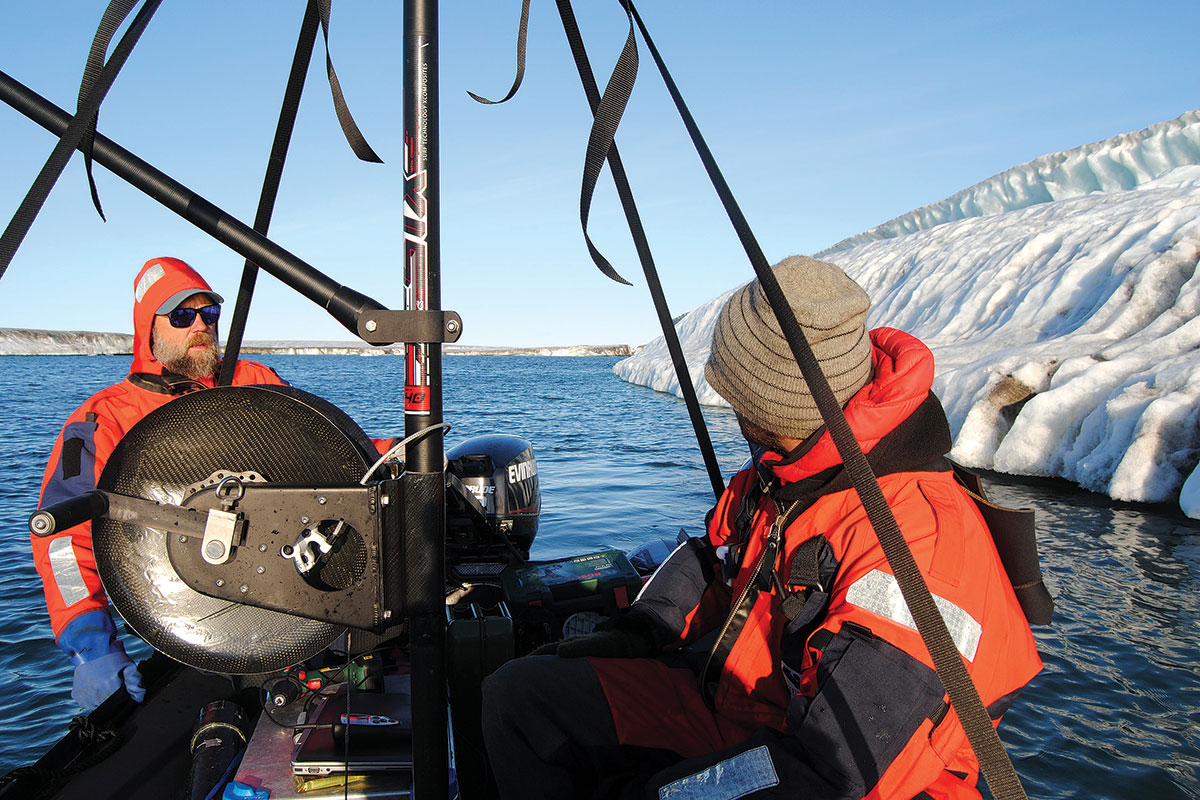

Near Station Nord, Northeast Greenland. // Photo by Wieter Boone

Bundling up for summer

Søren Rysgaard is a man of contradictions.

He researches global warming while studying Arctic ice, spends the summer in winter conditions and roams the vast Arctic region while examining tiny microbial organisms. He observes the disappearance of ice caps from the air and the appearance of anaerobic bacterial activity in the sea, and divides his time between spartan field stations and multi-million-dollar state-of-the art research facilities.

As well, Rysgaard conducts research in Winnipeg as well as Denmark, is the founder of the Greenland Climate Research Centre and, until recently, was the Canada Excellence Research Chair (CERC) in Arctic Geomicrobiology and Climate Change at the Centre for Earth Observation Science at the University of Manitoba.

During his CERC tenure, which ended in April 2018, Rysgaard became one of the world’s most renowned and respected Arctic ice experts. With CERC support and resources, he measured, explored and examined the disappearance of sea ice and the interface of that ice with the ocean and the atmosphere, while studying the way in which the warming of the Arctic affects the micro-environment, land, temperature, severe weather and northern wildlife and society.

“In both Canada and Greenland,” Rysgaard says, “changes in sea ice coverage have large implications for local communities as well as for commercial fisheries and businesses.”

Søren Rysgaard.

Working with more than 250 international scientists and students, Rysgaard divided his CERC research into two related tiers.

The first tier, he explains, focused on biogeochemical processes in sea ice and how changes in ice conditions may impact the Arctic in a broad sense from marine ecosystems and marine uptake of greenhouse gases.

The second tier, he continues, focused on enhancing understanding of the climate’s influence on the Arctic marine system and specifically on sea ice algal production.

“Our research efforts on sea ice have led to new knowledge on processes involved in ice formation and melt and how chemical processes in sea ice affect the carbon chemistry in Arctic waters,” Rysgaard elaborates.

“The melting of sea ice, algal production and dissolution of the observed concentrations of ikaite,” he continues, “resulted in melt water with very low carbon dioxide concentrations, which, in turn, increases the potential for seawater uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.”

These, he adds, also greatly affect pH conditions in sea ice and surface waters and hence, play a role in ocean acidification in Arctic seas.

Søren Rysgaard and Wieter Boone near Station Nord, Northeast Greenland. // PHOTO by Jørgen Bendtsen

It was in the course of uncovering these new dynamics that Rysgaard and his team provided the first-ever report on gypsum precipitation in sea ice and developed techniques, now used worldwide, for quantifying the three-dimensional distribution of gases and brines in sea ice and for studying frost flowers and chemical and biological processes in them.

“Dr. Rysgaard’s innovative and creative research has provided us with new insight into climatic feedbacks being recorded in Arctic Ice,” says Norman Halden, dean of the Clayton H. Riddell Faculty of Environment, Earth, and Resources.

“He also was instrumental in creating the university’s Arctic Science Partnership, which has opened doors and unique international opportunities for our researchers, particularly graduate students.”

Those graduate students acknowledge how fortunate they have been to work with Rysgaard. “Dr. Rysgaard always leads by example,” says postdoctoral researcher Karley Campbell. “At the heart of his approach,” she says, “is his respect towards fellow students and staff and that all ideas are granted thought and consideration independent of one’s position.”

Odile Crabeck, who completed his Ph.D. under Rysgaard in 2017, agrees with Campbell’s assessment.

“The joy and enthusiasm Dr. Rysgaard has for the research is contagious and motivational, which make him a great mentor,” she says.

“And, after so many years doing Arctic research, he is still strongly passionate and driven by his work.”

Recently, Rysgaard has focused that passion and drive on researching ocean-glacier interactions, the processes behind the melting of glaciers and icebergs, and the tracking of icebergs and ocean currents in relation to ice hazards.

“Through my many years in the Greenland and Canadian Arctic, I have witnessed that sea ice and glaciers are melting very fast,” Rysgaard explains. “Many of the glaciers I originally visited more than 20 years ago are rapidly disappearing.”

This, he adds, is a salient topic due to increased traffic and oil exploitation in the Arctic.

As Rysgaard pursues this newer line of research as a CERC laureate, he looks forward to working with the new Canada 150 Research Chair, Julienne Stroeve, who begins her tenure in September.

After spending hundreds of days as a CERC in the challenging and unforgiving cryosphere, Rysgaard is nowhere near ready to come in from the cold. After all, he knows better than anyone that there is still so much more to learn about thinning sea ice, thawing permafrost and the detrimental effects of climate change on the Arctic environment.

Ice-Breaking

Arctic Research

Søren Rysgaard was an ideal selection for the inaugural CERC program, launched by the Canadian government in 2008. The aim of the program, after all, was to enhance Canada’s reputation as a global leader in cutting-edge science and innovation, establish global partnerships and generate lasting social and economic benefits for Canadians.

During his CERC tenure, Rysgaard has done all of that on a massive scale.

One of Rysgaard’s first steps as a CERC was to create the Arctic Science Partnership, an extensive international research collaboration between the U of M, Aarhus University, the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and The Alfred Wegener Institute, that brings together the world’s leading Arctic scientists. He then led those scientists, and hundreds of students, on 30 major field campaigns, many of them to the most remote and unforgiving parts of the Arctic.

Working closely with his team, Rysgaard discovered numerous physical, chemical and biological processes related to sea ice formation, sea ice melt and the way in which sea ice affects greenhouse-gas exchange between the atmosphere and ocean. He also developed new techniques for measuring the global nitrogen cycle in the oceans, and published more than 200 papers on his research.

Rysgaard mentored and inspired countless young scientists and Arctic explorers in both the lab and in the field, and generated millions of dollars in global funding for new Arctic projects. In the course of doing all of this, he also turned the Centre for Earth Observation Science at the University of Manitoba into the world’s foremost intellectual hub for Arctic and climate change exploration and discovery.

Story originally published in ResearchLIFE Summer 2018 Edition. Read the full magazine online.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.