The UM STARlab team in the "clean room" at Magellan Aerospace

Actually, it is rocket science

UM’s first satellite is expected to launch in 2023

Listening to Philip Ferguson list off the projects he is involved with, you’d think he wouldn’t have time to sit and talk with me about them.

Ferguson is an associate professor in mechanical engineering, the NSERC / Magellan Aerospace Industrial Research Chair in Satellite Engineering at UM, and the director of STARLab, a suite of projects based in the Price Faculty of Engineering and where he is telling me about his work.

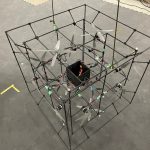

As we talk, beside me on a table is a cube-shaped structure about half a metre on each side, looking like a half-made Meccano kit or something constructed from an ancient Tinkertoy set. Across the room from us is a long wooden trough filled with sand, and what appears to be a truck with wheels at one end. In the centre of the room is a large area encompassed by netting. Scattered around the room are tables with computers where grad students are busily poring over data and displays. It looks rather like the set of a Big Bang Theory episode.

Ferguson explains: “My research aims to ‘make space accessible’ for communities. I’m currently working on a CubeSat design that would empower northern Inuit communities with ice and snow remote sensing data to help them assess ice safety. Climate change makes that more and more perilous for them.”

Ferguson and his team of grad students and other faculty are partnering with the town of Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut, and with outreach collaborators in Churchill. This satellite will be launched into a polar orbit, much like the next shell of Starlink satellites that is expected to give Arctic communities access to high-speed internet.

In fact, while emailing me about his work, because he lives in a remote area of Manitoba, Ferguson used a Starlink high-speed Internet system rather than the wifi or wired systems most of us use. It’s indicative of how satellite and remote sensing technology is so pervasive in our everyday lives.

While focusing on space technology, Ferguson is also experimenting with drones to supplement or enhance other projects. For example, the cube next to me is a complex drone within which a small satellite can be attached. The drone can then hover, accelerate and spin to simulate zero gravity, all while hovering in the STARlab in the UM Engineering & Information Technology Complex (EITC), so that the satellite’s spaceworthiness can be tested without actually launching it into space.

Ferguson predicts that within ten years, a satellite could be designed, built, tested and launched into space for about $250K, much less than the billions spent in previous decades. In fact, the UM satellite that is getting ready for launch was built for about $60K—a mere drop in the aerospace bucket.

He explains: “I’m just finishing a project that qualified a bunch of automotive-grade parts for space. This speaks to the ‘accessibility’ of space. It is no longer the case that satellites need to be built from ‘space-grade’ parts. We are doing research with Magellan Aerospace to create lower cost electronics, thereby improving the accessibility to space.”

“We even 3D printed many parts,” he adds.

The Ferguson lab is also working on a project that will help mitigate the challenge of unwanted space debris. Recently, the problem of pieces of decommissioned or damaged spacecraft in varying orbits which could endanger astronauts has been in the news and is of concern to NASA and the new US Space Force. Ferguson and his team are building a small thruster pod-like vehicle that could bring space debris back to earth autonomously.

Part of the problem in detecting and grabbing space debris is the tracking of the individual pieces. Ferguson’s team is also working on new kinds of sensors that could aid in tracking and locating materials of interest. These remote sensing strategies can be used by satellites to determine the thickness of ice in the Arctic, monitor herds of caribou, measure soil moisture in farmland, and even guide drones towards targets.

The drone side of his work is really taking off. Literally.

The netted area inside the lab is where they test drones and keep them from escaping down the hallways of the university. (“It’s happened,” he notes.)

Ferguson says there are plans to build a large structure in UM Smartpark where a multitude of projects can be built and tested, such as using onboard AI to steer drones and gather data remotely. The new facility will be known as “the Drone Dome,” and could be used year-round to test and fly drones and other craft. $2.1M in funding for the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) facility was announced on November 18, 2022, by the Honourable Dan Vandal, Minister for PrairiesCan.

The trench in the EITC lab that is filled with sand is in fact a testing area for drones that could navigate terrain on Mars and other planets. A larger simulation of Mars could be built inside the Drone Dome as well.

And then there’s the pigs.

This needs some explanation. Every year, tragic deaths occur when Canadians fall through the ice on lakes and rivers. Unfortunately, their bodies don’t always sink to the bottom because they have so much air in them, so they instead float to the underside of the ice and are trapped. When attempted rescuers search for them, nothing is found on the bottom because the bodies are above them, hidden from view.

But if a drone was able to penetrate the ice with lidar or radar, the bodies could be located more easily. And that’s where the pigs come in.

Ferguson and his colleagues (including Drs. Gordon Giesbrecht and Ian Jeffrey) have used hog carcases placed under water and beneath ice as human analogues, then deployed sensors above the ice to locate the bodies. It’s grisly, but it may be used to locate human victims of tragedy someday.

STARlab is one of the most unique facilities at UM, and with the development of the Drone Dome and the launch of a UM satellite hopefully in early 2023, Manitoba’s race for space seems like it’s just beginning.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.