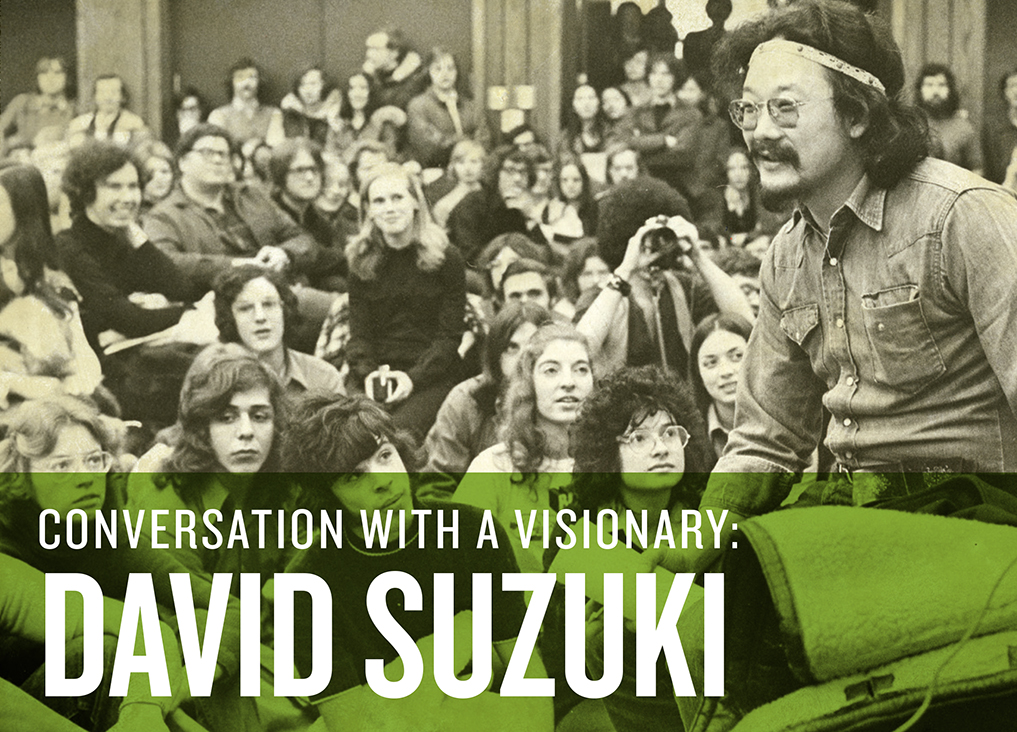

David Suzuki at the U of M in 1972. // Photo by Jeff Debooy, Winnipeg Tribune Archives

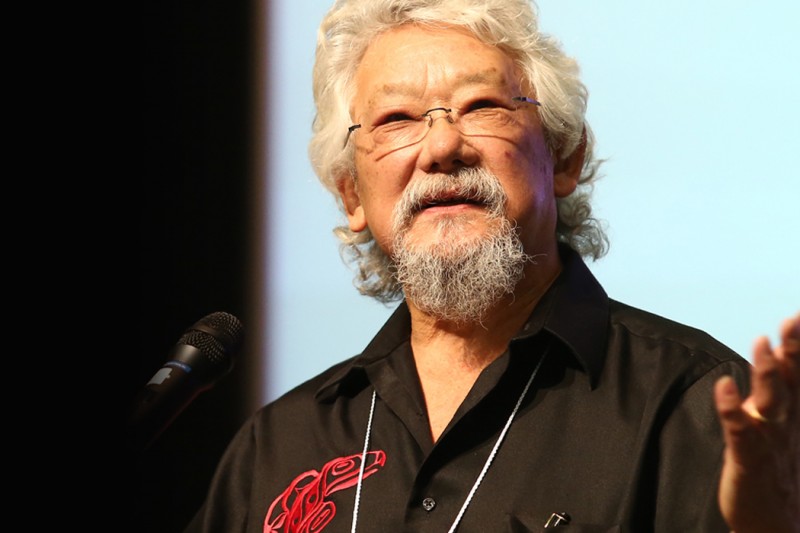

A conversation with a visionary

Since his debut in 1979 as host of the Canadian Broadcast Corporation’s long-running documentary series The Nature of Things, geneticist David Suzuki has cultivated the environmental conscience of Canadians from coast to coast. His connection to the U of M spans more than four decades to the early ’70s when Suzuki spoke with students.

In a recent visit to Winnipeg as part of a cross-country event — the Blue Dot Tour — to entrench the right to fresh air, clean water and healthy food into Canadian law, Suzuki sat down with President David Barnard for a conversation. Topics included the failure of environmentalism, its cause, and what is needed to catapult the issue from special interest to global imperative. Though governments, big business and universities were placed under the microscope during the discussion, Suzuki made it clear that the future of the environment depends on all of us.

On climate change

DAVID BARNARD: There’s a lot of scientific evidence about climate change. In addition, when our researchers work with Indigenous people in the North and Indigenous people in other parts of the world, they say that they’re aware of change. So, what’s needed for the general public and for governments to take action on these things?

DAVID SUZUKI: Well, I mean, we obviously need a new government. This government has clearly indicated that climate change is not something that they’re even interested in. Any evidence, any scientific evidence, they’re not interested in.

I mean, it’s clear just from their track record. The average Canadian understands very much. The polling indicates that climate is changing. You’re asking, ‘How do we bring them around?’ I have no idea. This is what I’ve been doing since I did the first program on climate change in 1989. And we’ve done literally dozens of shows on different aspects. I think the problem we face now is the enormous power and wealth of corporations. In 1988, Brian Mulroney was re-elected and interest in the environment was at its absolute peak then. George Bush ran for president and said, ‘If you elect me, I will be an environmental president.’ I mean, not because he cared at all about the environment, he didn’t, the public made him say that. So, to show he cared about the environment, Mulroney appointed his hottest star to be Minister of the Environment, moved him into the inner cabinet. Do you know who that was? Lucien Bouchard. I interviewed Lucien three months later. I said, ‘What do you feel is the most pressing issue facing Canadians today?’ and he immediately said, ‘Global warming.’ So that was impressive and I said, ‘How dangerous is it?’ and these are his exact words: ‘It threatens the survival of our species.’

BARNARD: That’s a good perspective on government and you also talked about business, but what do you think the position of the average Canadian is? You say when we’re surveyed we’re very aware, but are we changing our behaviour in a way that is consistent with what we say we believe?

SUZUKI: Yes, well, it’s very difficult when you don’t have the infrastructure for people to do the right thing. To abandon their cars for example, you really have to have top-notch transit. So, I mean, I think a lot of people are trying in their own way. When you look at the use of bikes in Vancouver for example, it’s tremendous. Vancouver, I think, shines as a real example where we’ve had growth of the city in the last 20 years yet in terms of use of cars it has dropped over the last 20 years, which is astounding as we’ve had greater densification. But we need bigger “big” decisions to be made. That is where governments simply aren’t reflecting that.

BARNARD: We just elected a new mayor and council, and transit was one of the big issues in the conversation.

SUZUKI: And it’s the issue in Vancouver too. And Toronto. Transit is the big issue … [But] while we’re on the climate issue, the Prime Minister of Canada spent five days in the Arctic, which is where the impact of climate change is simply undeniable. And never once, at least publicly, even said the words ‘climate change.’ And so, you know, this is a real challenge I think. And if Canadians see this as a real issue, then they’ve got to register that, in a democracy.

BARNARD: In 2012, you wrote a blog about the fundamental failure of environmentalism. One of the points you made there is that the environment has become another special interest and you were making a plea for a more bio-centric or more holistic view of it. It seems to me that we’re good at disintegrating and not so good at integrating. And we characterize quite a few things that our ancestors probably would have viewed more holistically as, in your words, special interest. For example, with respect to religion and spirituality: we want to put that in a box as a society whereas for previous generations, as you suggest with the environment, it would have been viewed differently. Would you agree with that hypothesis and, if so, what’s your observation more generally on our intellectual need or urge to disintegrate?

SUZUKI: Yes, we shatter the world. You just need to look at the way we communicate now. I really make a point of trying to listen to CBC Radio at six o’clock; it’s half-an-hour of news. In half-an-hour you may get 12 or 13 items. You may get a report from floods in Bangladesh, drought in Ethiopia, forest fires in Alberta and they’re all reported as if they’ve got nothing to do with each other.

And so you get these disconnected pieces, very short, and if they say, ‘And now we bring you an in-depth report’ you’re talking about a three-minute report. So, we shatter the world into shorter and shorter bits of news and we lose sight of the interconnectivity of everything. I think that’s part of the problem.

You’ve raised a number of questions here, not just one. I’ve said to Elizabeth May for years, although I’ve raised, or help raise, a lot of money for her and I’m glad she’s in Parliament, there should not be a Green Party. The idea that there’s a Green Party suggests then that, well, the environment is a special interest. The Greens are interested in the environment. And we saw before Elizabeth was elected, when they had an all-candidate debate or discussion on television, because there were no Greens there, all the reporters acted as if, well, we don’t have to talk about the environment: the Greens aren’t here. That’s ridiculous! But that’s what’s happened now. This is why we are fundamentally failing in the whole area of environmental issues. Because the environment is perceived as a fundamentally niche issue. You know, like, ballet for the ballet experts, sports for the sports freaks, and environment for the environment nerds.

The environment should be an issue for every party. And so this is why what we’re doing now with the Blue Dot Tour — the blue dot referring to the picture of Earth as seen from space — is to enshrine the right to a healthy environment in the Constitution. And there it’s a non-partisan issue, it’s that we think every Canadian should have the right to expect that our government guarantees clean air, clean water and clean food from the soil.

On universities

BARNARD: What would be your perspective on the responsibility or the possible response by universities to this kind of disintegration, this compartmentalization?

SUZUKI: Universities have enormous potential, it would seem to me. But you see, I got a bachelor of arts degree. At Amherst it was felt that in order to be a fully educated person you had to get a liberal arts degree. [Suzuki earned his BA from Amherst College (Massachusetts) in 1958, followed by a PhD in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1961.] So, even though I did an honours degree in biology, I was never allowed to take more than half my courses in science. I had to take courses in literature, in philosophy. And, I think that universities have become this gigantic thing servicing all kinds of people, the vast majority of whom I believe have no business being in university. I think that it should be looking at a group of scholars that want to explore knowledge at the cutting edge of human thought and that a liberal arts education should be at the heart of it. To train people with a bachelor of science degree, with maybe one course in English in freshman year, is absurd! People going out and using the most powerful tools humans have ever had and not having any background in philosophy or religion, I mean, I think that’s a failure of our educational system. And to me, the biggest change I thought was the universities going and welcoming corporations and private companies into the university and taking money from the corporations. You just have to go into the department of forestry at UBC to see why environmentalists like me were fighting against the professors. You see all these huge signs that say, ‘donations given by’ and all of the [names of the] forest companies. And that’s what the forestry department thinks they’re doing: training people to go out and service the forest industry. A huge mistake — to bring corporations into universities.

On cities

BARNARD: Where in Canada, or where in the world, are there some good examples of things that can give hope and that others can emulate? On a scale that people can actually respond to.

SUZUKI: There are lots of things going on not just in Canada but around the world. When you look at a city like Vancouver, we’re going into a civic election, but for two terms now we’ve had a mayor who has set his sights on making Vancouver the greenest city in the world by 2020. One of the things that we really lack is a target or a vision to which we can aim.

Development in communities generally goes in a helter-skelter way. A developer comes along and says, ‘I want to open a new subdivision’. You look at the environmental impact blah, blah, blah and then you approve that. And then you end up, 30 years later, with a city that you wouldn’t want to live in. Because there’s no overarching vision of where we want to go.

I think cities around the world are where the action is because, of course, that’s where the rubber hits the road.

BARNARD: Are there other good examples in Canada besides Vancouver?

SUZUKI: Well, we’ve elected a number of, I think, very progressive mayors in Edmonton, in Calgary, now we’ll have to see what happens in Winnipeg. Montreal, now we talk to Denis Coderre, there, and he’s going to adopt our declaration for a healthy environment.

I see people all over the place doing good things. What are they doing? Well, I think the fact that transit is top of the agenda says they’re trying to deal with the issue of cars versus other means. Vancouver’s use of community energy, where, for example, the heat in sewers is being used to heat buildings. This kind of approach, I think, is a very good one.

I have lost all respect for my Alma Mater. I’m embarrassed that U of M would dignify David Suzuki’s ramblings with inclusion in any U of M publication. He is an entertainer and a hypocrite. He stopped being a scientist a long time ago.

I was appalled when I opened up my last edition of UManitoba. More than appalled, I was enraged. Why? Because the person at the helm, the U of M’s highest office, the president, was featured in the whole centre section of UManitoba magazine having a “conversation with a visionary”. A visionary!! Who is this “visionary”? David Suzuki!! Perhaps the biggest environmental hypocrite in the country, and a professional purveyor of fear and myth.

Had the “conversation” not simply been a soap box opportunity for Suzuki, I would have had a different reaction. Where were the probing questions? The challenges to underlying theories? The questioning of conclusions? Instead, a fawning “conversation” between two people intent on reinforcing each other’s biases. I had always thought that Universities were a place where the search for truth, especially scientific truths, transcended the promotion of celebrity culture and their populist causes. My last donation to the U of M was my last, until once again, the institution demonstrates it is substantially more than an incubator for political agendas and celebrity culture.

I am happy to see the U of M engaged with leaders in environmental thinking like David Suzuki. He is an inspiring environmentalist who is never averse to speaking truth (as he sees it) to power. I want to see more interviews with thinkers like him. Not less. Keep up the good work.