Lions and tigers and bears? English prof’s new book, In the Tiger Park

English prof Alison Calder’s poetry is known for shining the light on all manner of “natural occurrences,” which nevertheless stand out.

English prof Alison Calder’s poetry is known for shining the light on all manner of “natural occurrences,” which nevertheless stand out.

Her new book of poetry, In the Tiger Park, published by Coteau Books, is about what exists at the edges of human experience, what’s out there but is largely unseen by the average human. It’s about ghosts, how these things operate as ghosts to us now, in this age — things that might have, in another age, occupied a more central place in our lives.

Calder is a professor in the department of English, film and theatre, where she teaches Canadian Literature and creative writing.

UM Today caught up with Calder to ask about her latest collection. She spoke with us about the central metaphor of her new book, how her writing has changed since her first collection came out in 2007, and why the university should consider creating a position for a poet laureate.

This is your second book of poetry and like the first (Wolf Tree), it addresses nature in some way. Could you expand on this?

Alison Calder: I don’t think about my poems so much as addressing nature as I do about them addressing location. I write about where I am and what I see there. Sometimes that’s “nature” – a field, a lake – but often that’s my street, or the parking lot across from where I catch the bus. I think it’s important that we pay attention to where we are. Here on the prairies, we’ve always been told that where we are isn’t important, that significant things happen somewhere else and that our environment is defined by absence – no trees, no people, no history. Of course, that’s completely wrong. And the best way to argue against it, I think, is to draw attention to the specifics of place. I’m very drawn to the histories embedded in a place, whether that’s a large-scale cultural history or just something that I happen to dig up in the backyard. I’d like my poems to confuse the boundaries between “nature” and “urban,” since those categories just oversimplify our experiences and make it hard to see where we actually live.

Both your first and second books include animals in their title. How do “the animal”/animals or the animate fit into this work? (You’ve also done some academic work on this topic; you could speak about that as well if you like.)

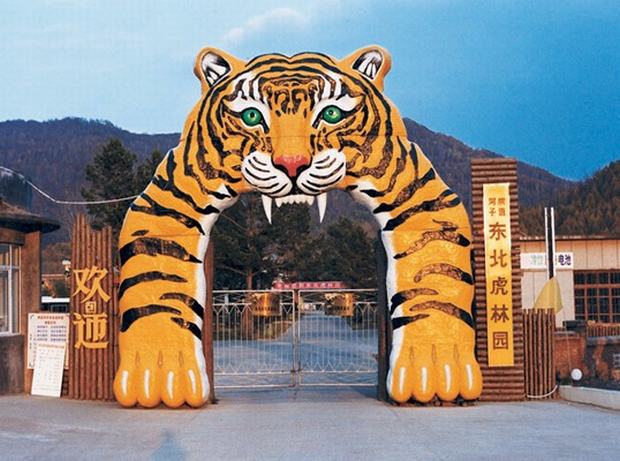

AC: The animal thing is kind of an accident! The tigers in the book’s title are real tigers in an actual tiger park, as the title poem describes, but they’re much more a metaphor for the perils of our everyday lives. Navigating our way through the day, we’re always in the tiger park, if that doesn’t sound too grandiose. The wolf in Wolf Tree, the title of my first book, is also a metaphor – it’s a label for a particular way that trees might grow and really has nothing to do with wolves. The animal that I really seem to be obsessed with, however, is the elephant – elephants are all over my writing, as subjects and as symbols. I need to get some kind of exorcist in before I can write anything else.

How has your writing — the product and/or interests/subject matter — shifted between your first and second books?

AC: This is a really good question because it speaks to a deep fear I have that I’m just writing the same thing over and over again. My first book looked a lot at power and how it manifested itself at different points in history in terms of defining the human – who got to be human and who didn’t. The first collection, like many first poetry collections, was kind of a grab bag of everything I’d been writing up to that point. The second book is a wee bit more focused, at least in terms of me being deliberately preoccupied with certain things. I’m really bad at writing about a set topic – I can’t just say “I’m going to write a book of poems about X” and have it work out. I have to sort of find my way into the conversation through a side door. For In the Tiger Park, I was thinking a lot about ideas of decay and regeneration, and how those things manifest themselves in everything from urban spaces to my own aging body. And a lot of the poems here, as in the first book, are about writing, though often not explicitly. I have a theory that all poems are about poetry.

How do you approach writing a poem or a series of poems, and has this changed over time?

AC: Yes, it has changed as I’ve learned what kind of a writer I am. I used to feel a kind of desperation about having to write poems – not a desperate urge to write poems, sadly, but just a huge pressure that I should be writing poems, why wasn’t I writing poems, would I ever write another poem, and so on. Being at a university contributes to this: there’s huge concern on the part of the administration with “output,” rather than on thoughtful, sustained engagement with ideas. They want a quick fix. Poetry doesn’t work like that, and it took me a while to get comfortable with the idea that I’m a slow writer – or slower than some people, that is. There’s a lot of research behind some of my writing, and that takes time to build up. Sometimes an experience or a detail will show up in a poem years after it happened. But waiting pays off.

What are the influences, from other writers to media or place, on your current work?

AC: Powerful influences are my immediate environment, books I’m reading, and language that strikes me as particularly fascinating. I love how the language that belongs to a particular place – a lab, or a football game, or a philosophical theory – just comes to life when you put it into a new setting. For example, “Inside the Lines,” one of the poems in In the Tiger Park, comes out of being a diehard CFL fan. I watch those games all the time. Football has a specialized language and recontextualizing it a bit really opens it up. During a game, you’ll often hear the referee asking the timekeeper to reset the clock, and it means, of course, that the timekeeper should reset the clock so that the game can play out accurately. But if you recontextualize that phrase and put it into a poem, suddenly it resonates in a whole bunch of different directions. How many times in my life have I wished I could reset the clock? Wouldn’t you like a do-over? And why do our knees hurt now when we climb stairs? It’s really a prayer: timekeeper, please reset the clock.

Are you working on anything else right now?

AC: Yes, I’m working towards another poetry collection (eventually) in addition to my regular scholarly writing. Strangely enough, my work with UMFA has led to a number of conversations with scientists, and now I’m writing a bunch of poems about glowing mice and transparent brains. I would actually love to see the [U of M] create a position for a poet laureate here at the U of M – it doesn’t have to be me, of course, but wouldn’t it be great to have someone training his or her creative eye on the work that’s done here? It would be a whole different way of engaging with the intellectual and emotional work that’s done here. If you want a true visionary, you need a poet.

***

About Alison Calder

Alison Calder’s first poetry collection, Wolf Tree, was published by Coteau Books in 2007. A selection of poems from this manuscript received the Bronwen Wallace Memorial Award for writing excellence by a writer under the age of 35. Her poetry has been published in journals and anthologies, most notably Breathing Fire: Canada’s New Poets and Exposed, and has twice circulated on Winnipeg city buses. She is the editor of Desire Never Leaves: The Poetry of Tim Lilburn (Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2007) and a critical edition of Frederick Philip Grove’s 1924 novel Settlers of the Marsh (Borealis, 2006), and the co-editor of History, Literature, and the Writing of the Canadian Prairies (University of Manitoba Press, 2005).