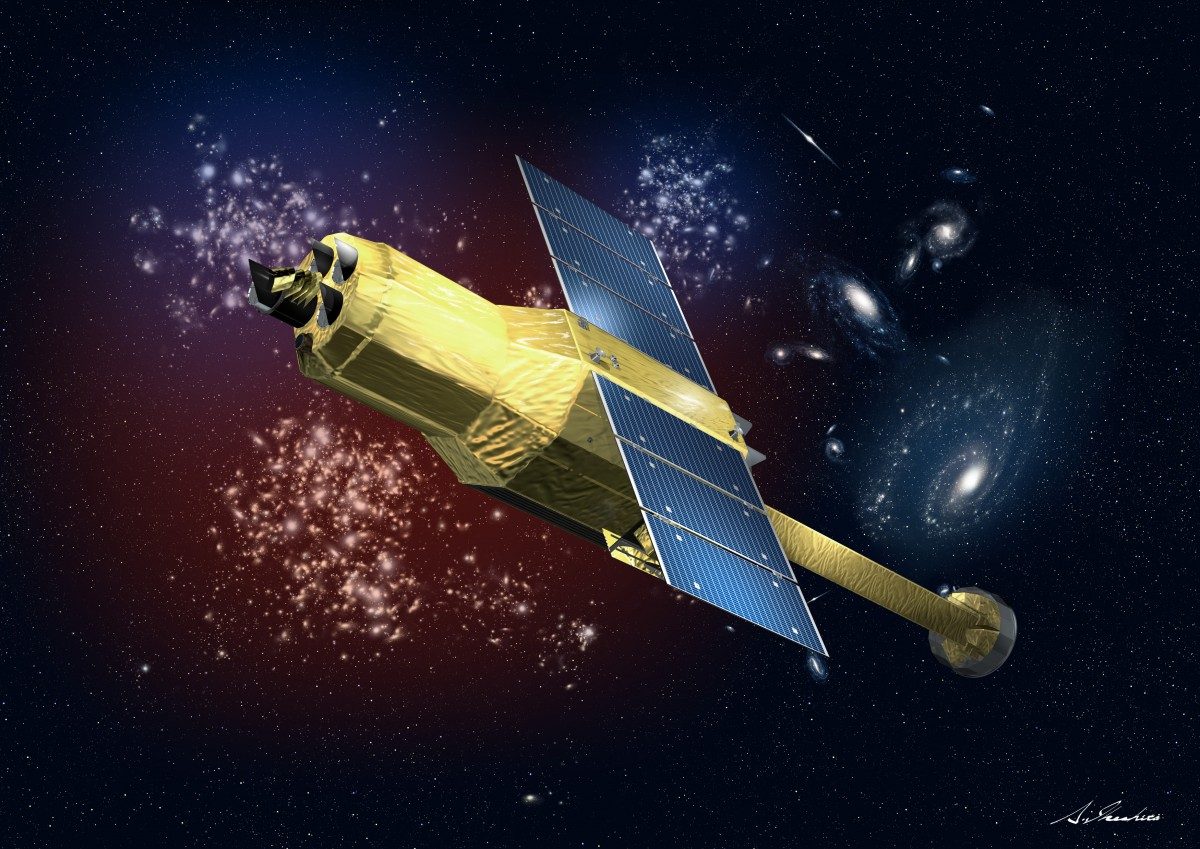

A RENDERING OF THE ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATION SATELLITES X-RAY ASTRONOMY SATELLITE "HITOMI" (ASTRO-H). // IMAGE: JAPANESE AEROSPACE EXPLORATION AGENCY © AKIHIRO IKESHITA

How do sunlike stars explode?

U of M astrophysicist part of international team announcing discovery of cosmic ‘recipe’ for nearby universe

Before its brief mission ended unexpectedly in March 2016, Japan’s Hitomi X-ray observatory captured exceptional information about the motions of hot gas in the Perseus galaxy cluster. Now, thanks to unprecedented detail provided by an instrument developed jointly by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), scientists have been able to analyze more deeply the chemical make-up of this gas, providing new insights into the stellar explosions that formed most of these elements and cast them into space.

In a paper published online in the journal Nature, an international team of researchers announce their discovery that the proportions of elements found in the cluster are nearly identical to what astronomers see in our sun.

“There was no reason to expect that initially,” said coauthor Michael Loewenstein, a University of Maryland research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The Perseus cluster is a different environment with a different history from our sun’s. After all, clusters represent an average chemical distribution from many types of stars in many types of galaxies that formed long before the sun.”

“It turns out you need a combination of Type Ia supernovas with different masses at the moment of the explosion to produce the chemical abundances we see in the gas at the middle of the Perseus cluster,” said Hiroya Yamaguchi, the paper’s lead author and a UMD research scientist at Goddard.

The Perseus cluster, located 240 million light-years away in its namesake constellation, is the brightest galaxy cluster in X-rays and among the most massive near Earth. It contains thousands of galaxies orbiting within a thin hot gas, all bound together by gravity. The gas averages 90 million degrees Fahrenheit (50 million degrees Celsius) and is the source of the cluster’s X-ray emission.

Using Hitomi’s high-resolution Soft X-ray Spectrometer (SXS) instrument, researchers observed the cluster in 2016 and recorded an unprecedented spectrum, revealing a landscape of X-ray peaks emitted from various chemical elements with a resolution some 30 times better than previously seen.

“Supernovae make the heavy elements essential for life,” says Dr Samar Safi-Harb, University of Manitoba, part of the Hitomi team. “One type in particular, called SN type Ia resulting from the explosion of white dwarfs, has been also used as cosmological probes for studying the expansion of the universe. Through these powerful explosions, galaxies (including our own) evolve in the metal-rich environments polluted by supernovae. A big question that Hitomi answered here is the mechanism which causes these types of explosions and the chemical make-up of one of the brightest x-ray clusters in the universe.”

Hitomi, which translates to “pupil of the eye,” was known before launch as ASTRO-H. The mission is an international collaboration led by JAXA, with contributions from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the Canadian Space Agency, and many other institutions in the United States, Japan, Europe and Canada.

More information on the Hitomi mission and the discovery is in the NASA news release.