Purple Martin. Photo by: Kevin Fraser, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Avian Behaviour and Conservation Lab (abclab.ca) Department of Biological Sciences

Life is a Highway: Dr. Kevin Fraser’s Research On Migration Is Right Where It Needs to Be

How climate change is affecting the purple martin and other migratory songbirds

There are advantages to living in the middle of a highway. Just ask Kevin Fraser, Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and expert songbird migration researcher. By chance, Fraser has found himself one of just a few scientists in Manitoba studying the migratory patterns of songbirds, many of which pass through here on their way from their northern breeding sites, to warmer southern climates, and back again. “There is a major flyway over our heads here in southern Manitoba as some of the billions of birds that depart the Boreal forest every fall, for example, are all kind of funneled right through here between the Prairies and the Great Lakes, so you get this huge concentration of birds …” says Fraser, warming to his feathery topic. As he points to a research poster in his office which shows the migratory patterns of the purple martin, Fraser’s good fortune to study in this particular location becomes even more apparent.

Purple martins are just one of the many species that pass through Manitoba on their way to warmer southern climes, returning here to breed. They are the Americas biggest swallow, weighing about 45 grams. Fraser has studied their migratory habits for years, learning in the process that these tennis ball-sized creatures actually fly thousands of kilometres from various parts of Canada down through Central America to their overwintering sites in South America. The bulk of our songbirds are migratory, and songbirds make up the majority of our avian population. For purple martins breeding in Manitoba, their extensive migration is approximately 20,000 kilometres, round trip. By studying their migratory patterns, Fraser has learned much of how the bird’s migratory behavior may influence how they will be impacted by climate change, as well as things such as identifying critical habitat that they need year round, from migratory stopover sites to their overwintering areas in the tropics, enabling the identification of threats from habitat loss. Fraser’s current MSc students (Amanda Shave, Lawrence Lam, Alisha Ritchie, and Amélie Roberto-Charron) have been investigating what factors at departure and during migration limit or constrain songbird behaviour, and how what happens prior to their arrival may influence their breeding success.

As with most things, timing is everything. Once the purple martin reaches its winter grounds, it must time its return to the North to match the optimal time for breeding. If an unusually warm spring here in Manitoba means an early melt and an advanced spring for plants and insects, the purple martins who arrive at their usual time may miss out on prime sources of food for their young. As a result, they might not have enough food, which may result in the birds raising fewer young and subsequent population declines.

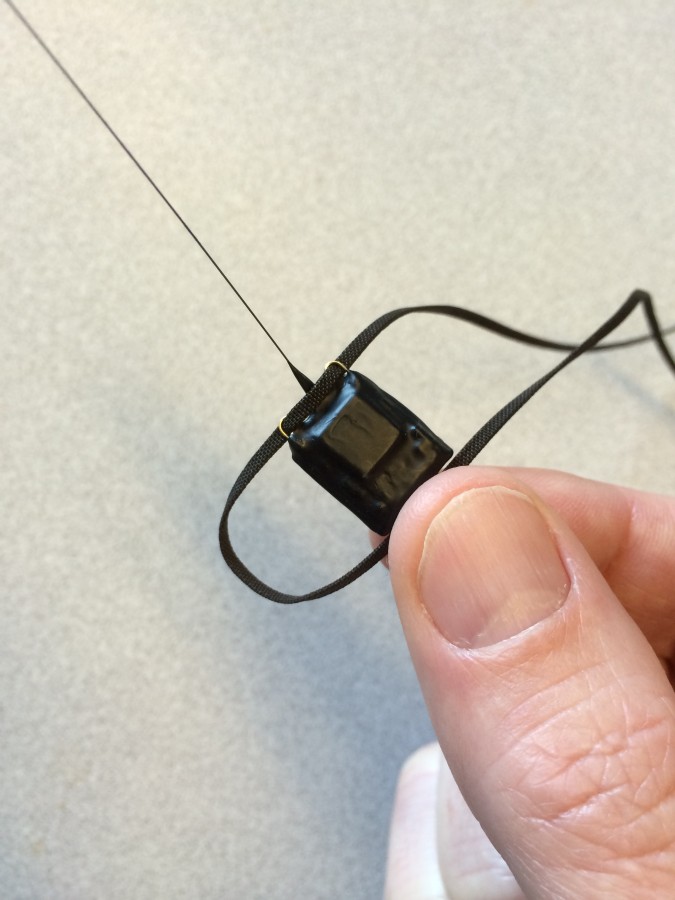

This was the scenario in the record warm spring of 2012, when Fraser and his collaborators tracked purple martins from Brazil to different breeding sites across North America, using tiny backpacks strapped to the birds. These devices weigh very little (less than five percent of the birds’ weight) but are capable of recording where the birds are in order to allow scientists to determine their migration.

Geolocator device. Photo by: Kevin Fraser.

Purple Martin Male, with geotag (just visible on lower back). Photo by by Jerome Jackson.

In 2012, the data gathered from the backpacks allowed Fraser’s team to determine that the martins did not receive the climate signals of an early spring, cueing them to come back earlier in response to the early melt here. Their timing was primarily driven by innate cues related to seasonal changes in day length in order to know when to return. Fraser’s Honours thesis student, Ellyne Guerts, will be studying the consequences of mismatched timing for purple martins this spring when the birds return.

These patterns do not bode well considering our declining songbird populations. However, Fraser and his team have recently learned something extraordinary. Contrary to popular belief that migratory birds may be relatively inflexible when it comes to their migration timing, they have found evidence that they may actually be able to turn back if they encounter extreme cold conditions.

“When birds were migrating up through North America last spring, a group of them … hit a real cold front … and they turned around and travelled several hundred kilometres back to Southern Texas, hung around there for a few days, then turned around and resumed their journey northward on their way to breeding sites here… It totally floored us.”

Unlike Canada geese, who overwinter in the Southern U.S. and are able to use local conditions such as rising temperatures to time their return up north, songbirds who migrate to South and Central America have no way to know what the weather is like at their breeding grounds. This discovery with regards to reverse migration is significant, as it indicates that songbirds may not be as inflexible as predicted, and may be able to respond adaptively to some types of bad weather that they face during migration itself.

Earth Day is April 22nd, and just happens to fall at the peak of songbird migration in North America. Fraser and his students will be ready and waiting for their return. To learn more about the work being done by Kevin Fraser and his students, please visit his research website, the Avian Behavior and Conservation Lab at: http://www.abclab.ca.